An Interview with Pinar Öğrenci

Aşît is a movie by Pinar Öğrenci is an artist and filmmaker based in berlin. She has a background in architecture, which informs her poetic and experiential video-based work and installations that accumulate traces of ‘material culture’ related to forced displacement across geographies. Her works are decolonial and feminist readings at the intersections of social, political, and architectural research and follow agents of migration such as war, state violence, natural disasters, industrial and urban development projects. Pinar’s works have been exhibited in many museums and art institutions around the world and she is the founder of MARSistanbul, an art initiative launched in 2010.

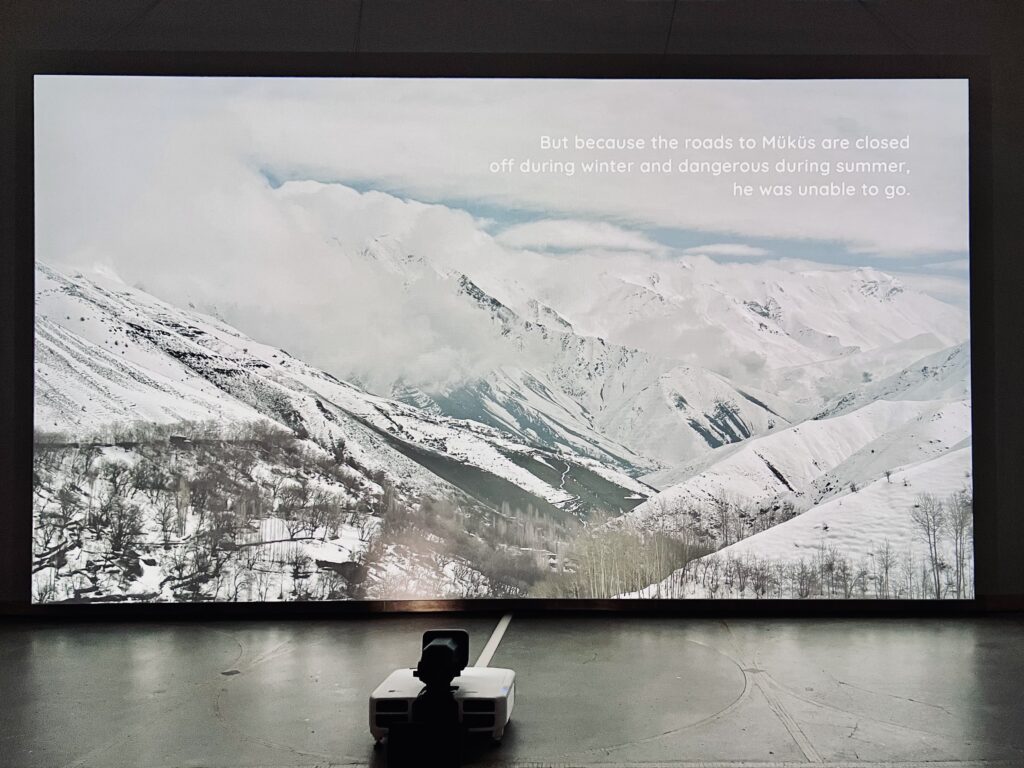

Pinar’s movie Aşît (2022) was commissioned and first screened in documenta fifteen. For Aşît, which means both avalanche and disaster in Kurdish, Pinar returns to her father’s hometown, Müküs, within the mountainous region in southern Van. On Turkey’s border with Iran, this former capital of the Urartian civilization, and the Armenian Vaspuragan dynasty, today has a dense urban population of mainly Kurdish speaking communities. The movie begins with a scene of the sky and then the camera shifts its gaze to some historical artifacts which tell us we are in an ancient land with a rich history. Then, we move to everyday life of the local people and we come across this military vehicle which we might even not pay so much attention to until we see more of military bases, prisons and then a huge concrete watchtower in the middle of the town. Immediately, the director cuts to a chessboard.

Sarazad sat down with the artist to discuss this movie as well as the artistic journey which has taken the artist to this point in her career.

Sarazad: Thank you very much Ms. Öğrenci for your time. We really enjoyed watching your movie in the Documenta and we actually had a chance to have a conversation with you there which was very fascinating. We have some general questions, but we are mainly interested to listen to you and see how you describe the process and methodology of your work. The first question can be about the background of this project. Can you give us an introduction about the background of your practice which resulted in making this film?

Pinar: Thank you for the invitation. I grew up in Van, this Iranian-border old Armenian-Kurdish city, and I moved to Istanbul when I was seventeen to study architecture. But of course I spent seventeen years in this city and it is a city full of natural beauty. It is surrounded by huge mountains that can be seen from the city center. Of course when I was a child these mountains were more visible because the buildings were lower back then. So we grew up looking up to these mountains.

At that time, speaking Kurdish was forbidden. Singing Kurdish, reading a book in Kurdish, everything was just forbidden and imagine that this was after the 1990s military coup in Turkey. Many people were in prison and it was hard to talk and discuss what was happening. We were young of course, but it seemed like whatever question we would ask about history was banned. No-one would give us an answer, even our teachers. So, there was a lot of pressure on the Kurdish people. And when I was fifteen or sixteen, it was the early years of the Kurdish movement in Van and this Kurdish area. My friends’ fathers were killed just over night or their brothers would disappear. I grew up in the middle of these stories and there was a great solidarity between us students. We tried to help each other, raise money or these sort of things.

Asking about the Armenians and the Armenian culture of the city was impossible. Whenever you asked “what happened to the Armenians? Where are they? Do you know any Armenians?” It was like it was haram. “No. Please don’t ask this,” they would say. Talking about the Armenians was a big big taboo. And of course we were children and we did not know much about this story, but we could feel it. When you went to the museum, there was nothing about the Armenians. There were artifacts about ancient civilizations, but then there is a big gap between the Turkish republic and the middle ages.

So, it is only natural that I have been working on forced displacement. Our society used to be a very good example of living together and during the Ottoman era Armenians, Greeks, Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Jewish and some Levantine people used to live together. Of course, it was not some kind of paradise. There were problems about, for example, taxes and they were not equal. But at least they were living together, and they each talked their own language. But WW I destroyed all these living structures and cultures.

When I went to Istanbul to study, Istanbul was partying. There was practically a kind of civil war happening in Kurdish cities, but there were no discussions or demonstrations and people were not aware of what was happening in Kurdish cities. The night life was booming, the rock music scene was flourishing and I really thought that we are living in two different countries. It was also a wonderful time for contemporary art, with many initiatives were taking place and many biennials and museums were being established, but at the same time, people were dying. You know, there was a very weird atmosphere in the air and was not just limited to that time in the 1990s, but this atmosphere still continues even on an institutional level and so this contrast has always stayed in my mind.

So, last year I was thinking about this part of our history and when I got an invitation from such a big institution like Documenta, I immediately said: “I want to do something about my hometown,” because it is my first and main source of inspiration. Of course, I have always thought a lot about the chess culture in my father’s hometown and I should say that my father was so proud of this chess culture. But at the same time, he was a gambler. He was a big gambler and instead of playing chess, he was actually gambling. So, for me it was not something which I was proud of. There was some kind of contrast between what made him and what made me proud.

There was also the impossibility to go to Armenia as our borders are closed and you cannot go directly from one country to other. I had some plans to go there on a three-month scholarship, but then the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan started and people advised me against going to there as it would be dangerous for me as a Turkish citizen. Ya’ni, just imagine that Armenia is very close to us, just behind the mountain, but you cannot reach it. That is way I was always thinking about the mountains and the borders, both physical borders and borders in our minds.

Sarazad: Well, all this is very interesting and one question that comes to mind here is about the multiplicity of identities that you brought up. It seems like even though you are looking at things from the point of view of the Kurdish identity, you are not trying to celebrate that identity. Instead, it seems like you are talking about the complexity and multi-layered form of identification processes in that specific location and your point of view seems to be quite critical when it comes to the idea of cultural purity. So, it would be interesting if you can elaborate a little more on that as it plays a significant role in this movie as well as the other projects that you have done.

Pinar: It is actually a very good question. The issue of identity is a big problem. I grew up in Van as a daughter of a Kurdish-Iranian father and a Turkish mother and there was always conflict in our family, sometimes even fights. And I always felt like I am in-between because I cannot speak Kurdish. So I am not accepted very well by Kurdish friends, Kurdish artists and society because of this. But then Kurdish language was forbidden and there were no infrastructure and places to learn it actually. But I also do not feel like a Turkish person. So, I think this not having an identity, at least not having a nationality, is a kind of an advantage.

Of course, I have always support the Kurdish movement and have always been against everything about the Armenian genocide, but I should also say that Turkish and Kurdish people are both responsible for the genocide. So it is really a difficult position for me as a half-Kurdish and half-Turkish artist to talk about the genocide. They were both responsible and this was a very big responsibility for me. Today, the Kurdish people face so much pressure since the establishment of the republic and so many small massacres has happened in different cities, but at the same time, we should not forget the Armenian genocide and the involvement of Hamidiye groups in it.

Using chess helped me to solve the problem. Instead of directly talking about communities which fight each other constantly, I tried to use chess as a metaphor for how we can even be enemies, but still discuss things, sit next to each other and talk. I always have this hard feeling of being …, not totally accepted by Kurds and also by Turkish people, but I feel like having no idea of nationalism is actually a big advantage, because I cannot support any one nation.

Sarazad: I think it is very interesting that the idea of multiplicity of identity take us beyond the very idea and makes us think about it. You immediately related this to the game of chess, which is of course very important in your film. There is also a very important reference in your movie about a prisoner who is playing chess against himself. And many we can elaborate bit on how these complex conditions feel like playing chess against yourself. My impression was that this act of playing chess is not about something external and is more about yourself. Am I right about that?

Pinar: Ya’ni, chess is a strategic game and is a metaphor for tactics and strategies. And to be able to have success in playing chess you have to remember your partners past movements and also their next possible movements. So, I used this quality of chess to talk about historical mistakes of the past, our historical denials and embarrassments, but also as a way to look to the future. Know you, maybe for the reconciliation of the Turkish and Armenian people.

I do not talk about all these things directly in the narrative, but the game of chess brings these possibilities to mind; what we did before, what is going to be next. In the film, I did not try to follow the movements of the pieces, like asking what the queen or the night are going to do next. I am not following all the moments of the game, but instead I try to see the chess tables as an everyday routine in the cafés. People come, set the table and play many times during each day. I saw chess as a symbol for the political arena which is constantly destroyed and then reconstructed again. So chess gave me the possibility for this kind of symbolic way of thinking.

In Stefan Zweig’s book The Royal Game, his character Dr B. is imprisoned in a hotel room and cannot speak to anybody. He finds a chess book, learns how to play and then plays against himself. So, it is a kind of a prison. And everything was resolved in my mind when I learned that in Portuguese the word xadrez means chess as well as prison. You know, before that I was thinking about how I can use this story. I was looking for the word “chess” in different languages when I came across this double meaning. And well, Zweig spent the last two years of his life in Brazil and wrote The Royal Game there. So, I thought he must have been inspired by this double meaning.

Then I thought that Müküs, my father’s home village, is a prison as well because it is surrounded by mountains and people are stuck inside of this town without being able to go out. There is also a lack of different kinds of infrastructure like roads, hospitals, schools. But I must also say that this disposition of Müküs can also be considered as some sort of advantage because the area was not destroyed by capitalism and the state apparatus. The state arrived in the area very late. If the state had arrived earlier, people would not play chess anymore and the chess culture would have been destroyed by some hydro-electric plan or some other big industrial project. So, you can image that time has stopped in this area, like a time machine. It has not changed so much.

If we want to talk about the landscape and the architecture, I immediately noticed that the asphalt roads brought all the structures of the state. State came, the road came and then the police station arrived and after that the prison and that big mosque. Then parks were built and named after Erdoğan or the July 17th (the date of the fake military coup). And after that those big ugly TOKI social houses. And in the film you might have noticed this big tower in the middle of the city. It is made of concrete and filled with guns. And you might ask why? And remember that in this town there has not been any serious clash between the Kurdish forces and the Turkish army as people were afraid of supporting the Kurdish movement because people are afraid of supporting the Kurdish movement. They already do not have any support from the government, so they are very scared of supporting any movement. They are just silent and still they built this huge tower in the middle of the town as a kind of fear mechanism. So, I tried to see the relation between violence, architecture, roads and how the state makes itself visible by this kinds of architectural infrastructures.

Sarazad: In contrast to these architectural and state structures, maybe we can talk a bit about the role of nature and how it is represented in the film.

Pinar: At first, I thought nature and the landscape_ the huge mountains, the water and the nut trees as a witness of what happened there because they have been standing there for centuries and they have seen everything, even though they cannot talk. I believe that violence destroys bonds, bonds between people and different Kurdish, Turkish, Armenian or Arab communities. Making relationships and bonds takes ages, but destroying them happens in a flash. It just takes a mere day or a war for them to be gone.

I tried to see how war and state violence destroys the bonds between us, between different communities, but also how it destroys the bond between humans and non-humans. I tried to see how the nature, landscape, animal husbandry and cultural relations are all connected. There is a scene in the movie where a man is naming different breeds of sheep and he says that all the names are originally from Armenian or Persian. And he is so proud of saying this. There is another scene where two sisters try to remember the original Armenian names of villages. All these are signs of the transnational fabric of the communities which used to live together. It is interesting how language can give us so much information about living structures.

Sarazad: There are a lot of metaphors and symbolisms in your work. The film has a very interesting narrative aspect and the framing and compositions are quite fascinating and the editing has a very pleasant poetic sense to it. All these are related to your way of practice as an artist. If you want to talk about your film production, how would you describe your work? How was the process of editing for you? We know that it was a quite fast production. How did the text come along? Are you one of those filmmakers who have a story board from the start and just follow that or do you prefer to improvise and talk to your camera?

Pinar: Ya’ni, I can say that I like improvisation and, you know, I think especially when you are making a documentary or an artist is making an experimental documentary, you cannot have a script. For this film, I wrote a script in collaboration with a Kurdish poet which was entirely about the city of Van. I ask the government for some permissions to shoot some scenes in the city’s museum and a castle. They did not say yes or no, but just said we have to wait. And after we had waited for two months, the camera team was already on the way, but still there was no news of the permission. So I started to think about what I should do. In the first script, the part about Müküs was supposed to come at the end of the Movie so that we can look at my father’s roots. But when we did not have the permissions we needed, I immediately thought maybe the end of the film can be the beginning of the film and I might be able to make a trilogy and go back to Van, my hometown, in those other movies. That way we did not need the permissions from the Cultural Ministry and I just talked to some local officials and got their approval.

One thing I can say about my filmmaking process is that I try to read a lot whenever I am making a film. When I was making the film, Gurbet Is a Home Now (2021), it was the beginning of the Covid pandemic and I was stuck in the house for three months and I read a lot about Berlin, the Kreuzberg neighborhood, the Turkish guest workers and trying to look at the representations of the guest-worker phenomenon in literature, poetry and music. This time also I tried to read almost all the literature and stories about Van and Müküs from different Kurdish, Armenian, and Turkish writers. I saw many documentaries about Van as well. I also tried to see how other artists have used chess in their works. Zweig has used it in his writing; thinkers like Benjamin and Brecht have used the concept of chess in their conversations to talk about their attempts in exile and what they were going to do next.

But, I think whatever you do behind your desk in your room and all the research you do in the library can only give you the background of your work. You should really spend time in your location. So, overall, I spend about a month in Müküs talking to local people from different age groups and genders. This presence in the field is really the main thing that opens up possibilities and spontaneous stuff that you end up using. Take, for example, the story of the cave and sheep which comes at beginning of the film. I heard this story when I asked people about the storytelling culture in the town and they immediately told me this story. It was a spontaneous question and later they told me that this story is the Kurdish version of Homer’s Iliad. When I heard the story, I told myself this must come at the beginning of the film because there is a character in the story called “nobody” and it explains everything; nobody accepts the responsibility of the genocide in my country. Everyone says they are not responsible. So, how is really responsible for this genocide?

This is also related to editing. I am an editing artist myself. This was the first time that I worked with a professional editor and we did the editing together. But generally I edit my films myself and if you know how to edit, you already start to edit when you are shooting. The best thing possible is that when you shoot something, you already know in your mind how to start, how to continue and how to look around you. And sometimes it is difficult to work with people in the cinema industry because they do not like spontaneity and prefer for everything to go according to the schedule. But sometimes you just come up with an idea to shoot this and that thing. So, starting to edit in your head when you are shooting is kind of the secret I would say.

Another thing I do is to listen to my subject. I just try to listen to the city, the mountains, the landscape. If you really look at your subject carefully, whatever that is, it will tell you something. For example, in the case of Müküs, you immediately see that it is a very slow environment. There is no traffic, no big bazar. There are not even many animals. We were at the top of the mountain and it was so cold that nothing was moving, not even a bird. So, I told myself that this movie should be slow. The slowness of the space can be represented in the slow shooting.

When you listen to your subject and your environment, you might find things that fit into your narrative. For example, when I heard the story about the rooster, I thought it should come at the end because I wanted to give some references to today’s disasters as well. You know, the sound of the rooster reminds me of the disasters that we are expecting, or the ones that we are living through right now. We started the shooting in the winter, with all the snow, and finished it springtime, which for me was very symbolic because the Armenian genocide happened in April and we were also shooting at the same time during the last week of April. The first Armenian rebellion in defense of in the year 1896 happened during the spring and was violently crushed. That is why we finished the film in spring.

Sarazad: The artistic language you have reached in this film is particularly interesting. The movie has a personal aspect, but you have decided not to use any voice-over narrative. Instead you chose to limit what is said directly to short texts which are playfully positioned in different parts of the screen. It seems like, generally speaking, your expressive strategy is through saying less, pointing to very important things in passing and communicating truths through your characters’ lines. How did you reach this artistic language?

Pinar: Well, when I was making the movie, I was thinking if, as an artist and the director, I should talk during the film or not. Then I thought to myself that if I speak it is going to be in Turkish and what was I to do in Turkish. Turkey has already invaded this area, so using Turkish would have been a second invasion for the film. English would have been weird as well. So, I decided that I should stay behind the scene, not talk and instead let the people speak.

And of course the questions and answers were really important. I really tried to find good-speaking people and good replies for the film, as if it were not a documentary. We recorded the conversations many times because sometimes they would become very long and had too much details. And, well, we were also translating everything between Kurdish and Turkish. Sometimes, I would say: “this is too detailed,” and I would ask people to make things shorter.

I have learned from experience that you should not use too many words, because the landscape also talks for itself. For example, there is no need to talk about the security structures and soldiers because you can easily see them in the town. You can see how military vehicles constantly patrol it. You can just give the viewer an idea, show them some traces of how people’s daily lives are affected by violence, how, for example, animal husbandry is affected. Instead of mentioning how many people were killed or presenting the data about violence directly, maybe you can talk about the stories of trees, water and land.

I also tried to pay careful attention to the sound recording as well. For example, we recorded the story of the cyclops and “nobody” which comes at the beginning of the movie tree times. The first time, a man was telling the story and it turned out to be a little to didactic. We recorded the story a second time with another guy and it did not have much soul. Then, I asked the sister of the last guy to tell the story and she was immediately acting and taking space and conveying the meaning of the story. It also happened with the two sisters who were saying the old Armenian names of villages. At first, I could not decide which one I should choose because they were both very good. So, finally I decided to record the scene as a conversation where they would try to remember the names together. I thought that this way the scene would be more spontaneous and interesting.

There was another interesting point as well. I was really happy that people accepted to talk. Because we were talking about genocide and in these small cities people are usually afraid to talk. They first do not accept it and they are also afraid to bring it up. So, I was really pleasantly surprised that they were open to talk. And I tried my best to protect them. They stay anonymous and one reason I did not want to show people’s faces was that it could have been dangerous for everybody. In general, also, I usually prefer not to use the direct images of people and I try to dedicate more space to their surroundings and spaces they live in. The space and architecture can tell us so many things about the social, economic and historical aspects of each place. That was the reason I tried to show more landscape, coffee houses, the bazar, and the other places people live in.

Sarazad: You talked about how you try to read and get yourself familiar with the literature and art about your subject matter. One of the very especial features of the movie is how you have used the music of Hayrik Muradyan, which apparently you came across by chance. Can you tell us a little about your use of his music?

Pinar: Oh, I should definitely talk about it because it is very beautiful story. I came to know Muradyan through a Kurdish teacher who had to leave my hometown, Van, during the 1990s because of political reasons. He now lives in Istanbul and he has written many things about Van. It was important for me to look at what had been written by local people. So, this teacher had also written many articles for the local newspapers some of which were published and some were not. But he sent me all his writings. And he had mentioned Muradyan and that he was from the village of Çatak.

When I listened to his songs, I really loved his songs. He also looked like my father, you know, angry but also very cute. So, I liked the music so much, but I still did not know how I could use it because he was from Çatak, not Müküs and the movie is not about Çatak. I work with an Armenian curator and I asked her to do a bit of research about Muradyan and she immediately found The Mountains of Müküs album. At the same time, I was reading a story by Franz Kafka which Benjamin and Brecht discuss in their conversation. The story is called The Next Village and in this story there is a character of a grandfather who says “sometimes life is so short that you cannot see the next village.” I said to myself that Muradyan was also so young when he was forced to leave that he never got the chance to see the next village, but he went on to write songs about and sing for this next village, about the mountains, the animals, the bazar. So, it was a great coincidence.

When I was doing research, I was secretly hoping that I would find something about my own dad. Even though my initial and main idea was not to make a movie about my father, I was still hopeful. And then when I learned that the name Hayrik in Armenian means father, I told myself: “Pinar, this is the father you have been looking for all this time.” It was not important whose father he was. He is the father of Armenian folk music. Finding Muradyan’s family and good-quality versions of his songs were not that easy, but finally we came to contact with them and fortunately they cooperated with us.

Sarazad: Your film was shown in the Documenta 15 in Hessisches museum in Kassel and was accompanied by an installation. Could you tell us a little about that installation?

Pinar: Well, the installation consisted of a big curtain made by sewn paper tissues. I usually use this as a projection curtain for my works. In my culture, and maybe in yours, handmade tissues are a symbol of love and in the past people used to give them to each other as a kind of a gift. They would write some notes for their lover on them. But of course the paper tissue is also a symbol of mourning and mourning is a big part of life in my hometown. People constantly die not only because of state violence, but also because of natural disasters.

For example, in 2012 we had an earthquake and more than one thousand people died. And then an avalanche might happen and another forty people perish. So, death is really a significant part of life in this region and I wanted to do something about this issue of mourning. I knew some women who are originally from smaller towns around Van and who lost their homes and were displaced because of the armed conflicts of the 1990s. So they had come to Van and used to live in poor areas. Then the earthquake happened and they again lost their houses and had to move to slum-like compounds created after the earthquake in which they are still living in. I asked these women to make this curtain for me together hoping it could be some sort of economic support for them as well.

At the same time, the shape and white color of this curtain gives an idea of the mountain, snow and avalanche. Another point was that I wanted to cover the entrance to the exhibition area to make it a more intimate space. The museum hall was long and rectangular and a lot of light entered the hall from the entrance. So, in a way the curtain was also very functional. It cut the light and created a room from screening.

Sarazad: What is the significance of location in the presentation of your work. Because, for example, when you are presenting your work in Germany, this country has a completely different relationship to Turkey which adds another layer of complexity to the screening. And there is presenting your work in the context of Kassel with all the drama and crises that Documenta had this time. So, where do you like to present this film. Who is your audience?

Pinar: I would say my audience was the international audience. In Turkey, people already know everything I would say, when I say Armenians were all displaced from the country they belonged to. So, I do not thing it would be that interesting to tell these things to Turkish people. And, in fact, they do not want to listen to these kinds of stories and they dismiss them as clichés. They do not want to hear these stories and they do not want to talk about it. But when you tell this to the international audience, it is more interesting because they are not aware of what happened.

Many people think that the first genocide happened during the WW II, but the Armenian genocide might actually be the first one and in the WW I Ottoman forces were fighting along Germans. And, in fact, Germany did nothing to stop the genocide. They themselves were even part of the crime. At that time, there were many German spies, soldiers and military officers present and they were of course all part of the plan. Actually, Hitler has an important speech delivered when he was about to attack Poland in WW II in which he says: “Who remembers Armenians today? Just go.” So, in a way, we have a similar history of genocide in Turkey and Germany. The difference is that Turkey does not accept that it was a genocide, but Germans have accepted that.

So, for me this film was somehow an act of apology. Because I think we are all responsible. We are part of this. Maybe our ancestors were part of it. Who knows. Only some Kurdish parliament members and writers have accepted their responsibility and have apologized. So, I think it is very important for each person to speak up and apologize for ourselves. If it is not yet possible to have a collective apology, we can do it for ourselves. So, this movie was kind of my apology.

Sarazad: So you are playing chess with yourself too?

Pinar: Exactly.