Autoethnography is a research and writing style where personal experiences are interjected into ethnographic writing. As a form of self-narrative, autoethnography places the self within a social context. Here, writing oneself is similar to “writing culture” (Clifford and Marcus, 1986).

As an academic genre autoethnography has expanded in the past ten years within social sciences and humanities, such as art, communication or education studies. However, it is not popular among anthropologists. Today, there is The Journal of Autoethnography (published by University of California Press) and an annual conference in the US. Several handbooks have published about it and countless artistic, non-fiction, cinematic works have been produced that are presented as autoethnographic.

Two Iranian examples

The autoethnographic documentary Nakhandeh dar Tehran (Unwelcome to Tehran, 2011) by Mina Keshavarz is about herself and a handful other young women who have moved to Tehran from other parts of Iran to start a single life, free from surveillance and control. Some key scenes in the film are shot onboard trains and long-distance buses or in terminals. The film illustrates single women’s continual struggle to cope with the obstacles in their daily lives. We see them in constant negotiation with their families and the surrounding society to justify their choice.

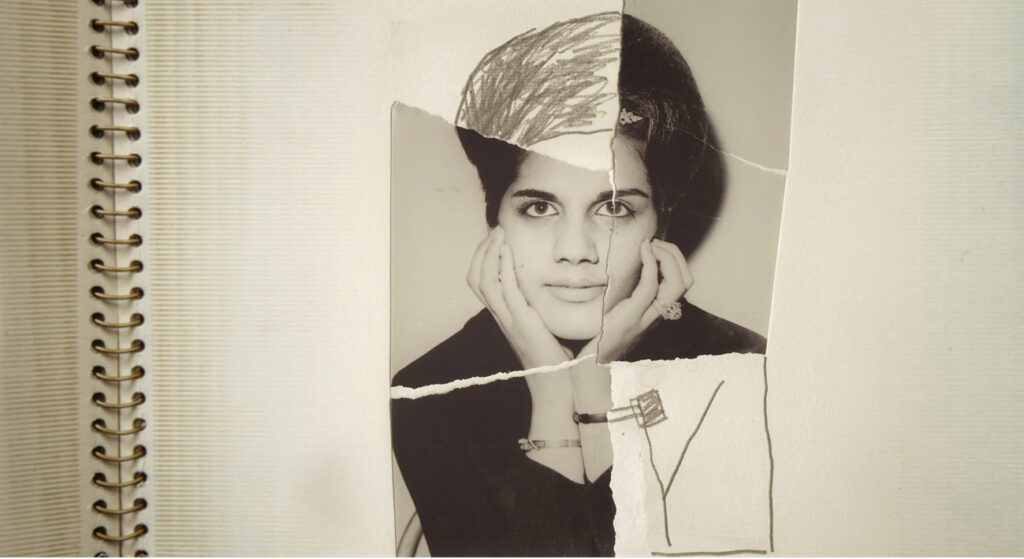

Radiograph of a Family (2020) by Firouzeh Khosrovani is a documentary of the director’s parents’ lives, marriage, jobs, emotions. The film is made with family photos and the main location is her parental house. Through the story of an upper middle-class Tehrani family, the film depicts the political and ideological tensions Iranian society has gone through in the 1970s and 1980s.

However, it is significant to emphasise that autoethnography is not autobiography. While the latter focuses inward, the former focuses outward. In autoethnography, one does not focus either on one’s own subjectivity or on the objectivity of the world, but on what emerges from the space in between.

For me, the most interesting and inspiring intellectual questions have emerged from the space of inbetweenness, where structures are displaced and individual’s (legal and social) status is socially and structurally ambiguous: between here and there, between now and then, between you and me, between human beings and citizens, between home and homeland and between legal and illegalized people.

Autoethnography offers a research method and a writing genre to explore this betweenness. And, it is in this gap that there is a chance to link and to integrate my stories into the experiences of others, including those of the readers. In this way, more people can make a connection with my stories. Unlike a depersonalized narrative, autoethnography asks its “readers to feel the truth of their stories and to become coparticipants, engaging the storyline morally, emotionally, aesthetically, and intellectually” (Ellis and Bochner, 2000, 745). Needless to mention, my engagement is not only political or academic, but emotional as well. Autoethnography becomes an ‘emotional participation’ (Hage, 2009), that is, to share the same feelings of anger and sadness with the people in the field.

Undoubtedly, all ethnographies are colored by the authors’ emotions, positionality, personal background etc., but this does not make them autoethnography. Interestingly, autoethnography is more popular among other disciplines (such as education, art, communication) than anthropology. It is a compelling question to be investigated why it is so.

In my years as an anthropologist, I have been amazed at how my undocumented interlocutors’ experiences recalled, confirmed, overlapped and completed my own experiences of borders. One interesting aspect of the autoethnographic text is that the distinction between ethnographer and others becomes blurred. Similarities between the interlocutors’ subjective experiences and my own blurred the distinction between anthropologist and interlocutors. Autoethnography links the world of the author with the world of others. This linking and communicability of experiences is the core strength of autoethnography.

This is, in Walter Benjamin’s meaning, the art of storytelling. In an essay from 1936, The Storyteller: Observations on the Works of Nikolai Leskov, Benjamin shares his concern about disappearance of the art of storytelling (2006 [1936]). For him, the new form of stories, the printed novel, had led to a time empty of shared experience. Benjamin believed that the new form of telling stories had resulted in the vanishing of the communicability of experiences in the modern world. In the information age, there is no space for reflection and communication of experiences. Unlike novels (a one-way channel of information), storytelling integrated the story into the experiences of the audience. In this way, more people could make connections with the story. A storyteller goes inward, inside herself to come out with a story. She makes her own experience into the listeners’ one. Benjamin built his argument on the differences between two German words for experience: Erlebnis and Erfahrung.[1] In English, Erlebnis is translated into individual and immediate experi-ence, while Erfahrung means accumulated and collective experience. For Benjamin, a consequence of modernity was the end of Erfahrung: firstly, the continuity of subjective life linking the past to the present was disrupted; secondly, the communicability of experiences was ruptured.

Autoethnography offers an opportunity to communicate, link and share experiences. By doing so, the individual, immediate and isolated experiences can be linked to the collective, accumulated, historical experiences. Bringing the individual and isolated experiences together and making them historicised is a resistance against the recurrent construction of the categories of refugees, migrants, asylum seekers etc. The accumulated and linked experiences of the storyteller and her audience shift the focus from such a category, as an ethnographic object, to the practices of the national order of things and the conditions this order impose on migrants or nomads.

Oppositional Look

Autoethnography for me was a way to survive academia. My body and my history as ‘tribal’ (Bakhtiari) and migrant (in Europe) affect how I experience the discipline. My approach to some issues differs from many of my colleagues. It happens quite often that I find myself in the “outsider-within” position (Collins 1986, in Williams 2001), that is, being a racialized scholar among white scholars who study racialized groups. My interventions against the ever-present domination of whiteness in migration studies have turned me into, in Edward Said’s words, one of the “nay-sayers” who always feels “outside the chatty familiar world inhabited by ‘natives’, the world of exile which is “constantly being unsettled and unsettling others” (Said, 1994, 39). For Said, the best metaphor for the “nay-sayer” and public intellectual is the exile, the out-of-place public intellectual, “whose place is to raise embarrassing questions, to confront orthodoxy and dogma” (1994, 9). For Said exilic consciousness and ‘outsiderhood’ is crucial for shaping of the intellectual’s critical look. Being exile, unfitted, and accented is a force of marginalisation and exclusion, but it can be a condition of empowering as well. Another exile, Cuban-American scholar José Esteban Muñoz (1999), saw potentialities for creating alternative spaces and politics he conceptualised as ‘disidentification’. In his work on racial and queer politics, he saw disidentification as a subversive act of transgression, creation, and radical imaginary.

In autoethnography, there is potentiality for a democratisation of knowledge, partly by making the knowledge accessible to non-experts and partly by challenging the hierarchy of knowledge in which “objective analytical expertise is valued higher than the knowledge arising from lived experiences and emotional responses” (Williams, 2001). Furthermore, by offering non-western scholars an alternative genre, autoethnography can adopt a critical stance that can challenge the dominant way of producing knowledge. It can be used as a way to confront the division between North/theory and South/field. Autoethnography can therefore provide the anthropologist with a “potent methodological means of engaging in a discursive and representational space for voices hitherto unheard or actively silenced, thereby posing a direct challenge to hegemonic dis-courses” (Allen-Collinson, 2013, 15). Autoethnography can also offer means for those migrants who have not been, in Rancière’s terms, visible and audible to tell their own versions of stories and challenge the white-dominated fortress of academic migration studies. Autoethnography for me is a reaction to how I was invented by the Swedish media, reduced to my migrant victimcy, redefined not as a subject who is able to theorise, but merely as an “experience” to be diagnosed.

Autoethnography is welcomed by marginalised and racialised people, such as migrants who are eager to tell their own stories. In precarious conditions storytelling becomes a way to conceptualize the life. After two decades in the academia, rather than identifying myself as a scholar, I see myself as a storyteller who integrates individual experiences into the collective ones. My stories gain their narrative power from the spaces in between these experiences. As mentioned above, the spaces in between, or the gap, are where Rancière (1992) identifies the place of politics. Edward Said also identifies the gap, where the exiled and homeless intellectual lives, a site of critical and oppositional engagement (Said 1994).

For me the main aim of my autoethnographies has been to link, to connect, human experiences. This is the power of stories. Migrants, refugees, and travellers without paper are great storytellers. If you have spent enough time with them you know it. Where does the need and passion for storytelling come from? Multiple precarities, all-pervading shadows of death, uncertainty all demand stories. For the displaced people stories and storytelling is a way to resist forgetting and being forgotten.

Not surprising that my autoethnographic book is well-received particularly by people who are migrant themselves or have migrant background.

Writings of several racialized postcolonial feminists, such as bell hook, Sara Ahmed, Ruth Behar, and Gloria Anzaldúa , who have lived and worked in the borderlands, along not only one but multiple borders, have elements of autoethnography. They reminds us that private is political and challenged the dichotomy of emotion (female) and science (male). We know that they have faced difficulties for not being taken seriously. They were criticized for their ‘unscholarly’ writing style. Their ‘bastard’ language, mixing emotions and theories, personal and politics have been regarded a threat for the white, male mode of knowledge production which is based on depoliticized, depersonalized, neutral theories.

This genre, thus, is preeminently decolonizing, a epistemological space for practices, experiences and performances to resist the colonizing whiteness within the academia and beyond (see Chawla and Atay 2018). In a recent Special Issue of Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies (Vol 18. No. 1) we see how racialized scholars use autoethnography as a radical form of embodied knowledge claims that resist the normative knowledge production as a colonial tool (Dutta 2018).

Autoethnography gains its narrative power from the concept of witnessing. The significance of the voice of the witness is that the witness has been there, has seen what happened. Witnesses have themselves lived the disaster. They can retell the story and unfold the event with first-hand authority. The radical insecurity migrants experience in their everyday life, from the sinking boats in the Mediterranean Sea to detentions centres or when facing lethal racism, demands explanation. Why? Why am I here? Where does this hate come from? Through autoethnographies and life stories we attempt to find something meaningful in the meaningless violence. Finding glimpses of hope in the dark time of racism and hatred. The political and existential insecurity, involves the mysteries and silences, necessitate narrations. Autoethnography is a resistance against this imposed insecurity, the imposed silence. Furthermore the autoethnographic voice of the racialized other reveals the need of showing sensibilities towards migrants’ fundamental right to opacity, that is, that not everything should be seen, explained, understood, and documented.

Recent queer feminist scholars such as Lauren Fournier uses the concept of ‘autotheory’ a framework for theorizing one’s lived experiences, i.e. to theorize the personal as the political.

Similarly, ‘autocritique’ (Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson) blurs the boundary between cultural critic and self-life narrative.

Autoethnography became a way to talk back and to resist being invented and re-invented by others (Khosravi 2010). Writings of several black, indigenous, or migrant feminists, such as bell hook, Sara Ahmed, Ruth Behar, and Gloria Anzaldúa, who have lived and worked in the borderlands, along not only one but multiple borders, have elements of autoethnography. Their works remind us that private is political and challenged the dichotomy of emotion (female) and science (male). We know that they have faced difficulties for not being taken seriously. They were criticized for their ‘unscholarly’ writing style. Their ‘bastard’ language, mixing emotions and theories, personal and politics have been regarded a threat for the white, male mode of knowledge production which is based on depoliticized, depersonalized, neutral theories. This genre, thus, is preeminently decolonizing, offering an epistemological space for practices, experiences and performances to resist the colonizing whiteness within the academia and beyond (Mohammed 2022, see also Chawla and Atay 2018). For many of us autoethnography as a radical form of embodied knowledge is an act of epistemic disobedience.

For authoethnography body and embodied experiences are central. Body is the site for theorizing and producing knowledge. It means theoretical thinking penetrates into daily experiences. Epistemology is intertwined with being in the world and thereby theory and praxis or practice are not separated. Autoethnography can be both pedagogical and activism.

And this means hope.

[1] In Swedish there are also two words for experience. The former is upplevelse and the latter erfarenhet.