History often contains blank pages, yet the events of Dhofar are barely traceable with faint hints and blurred imagery. Even after over half a century as well as major political shifts, the memory of Zafar rebellion and conflict lingers in our collective consciousness. This enduring obscurity is rooted in “silence”: a silence that began with the ruling powers of that era and still persists among the survivors today.

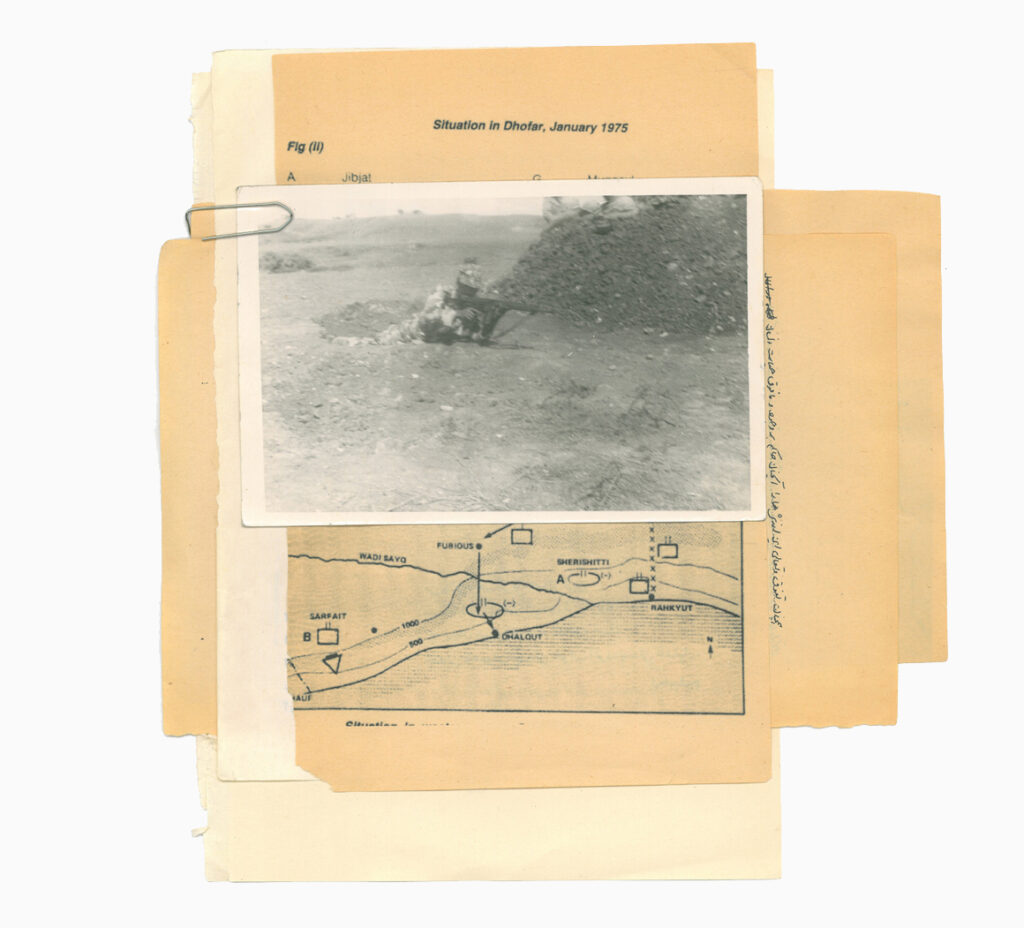

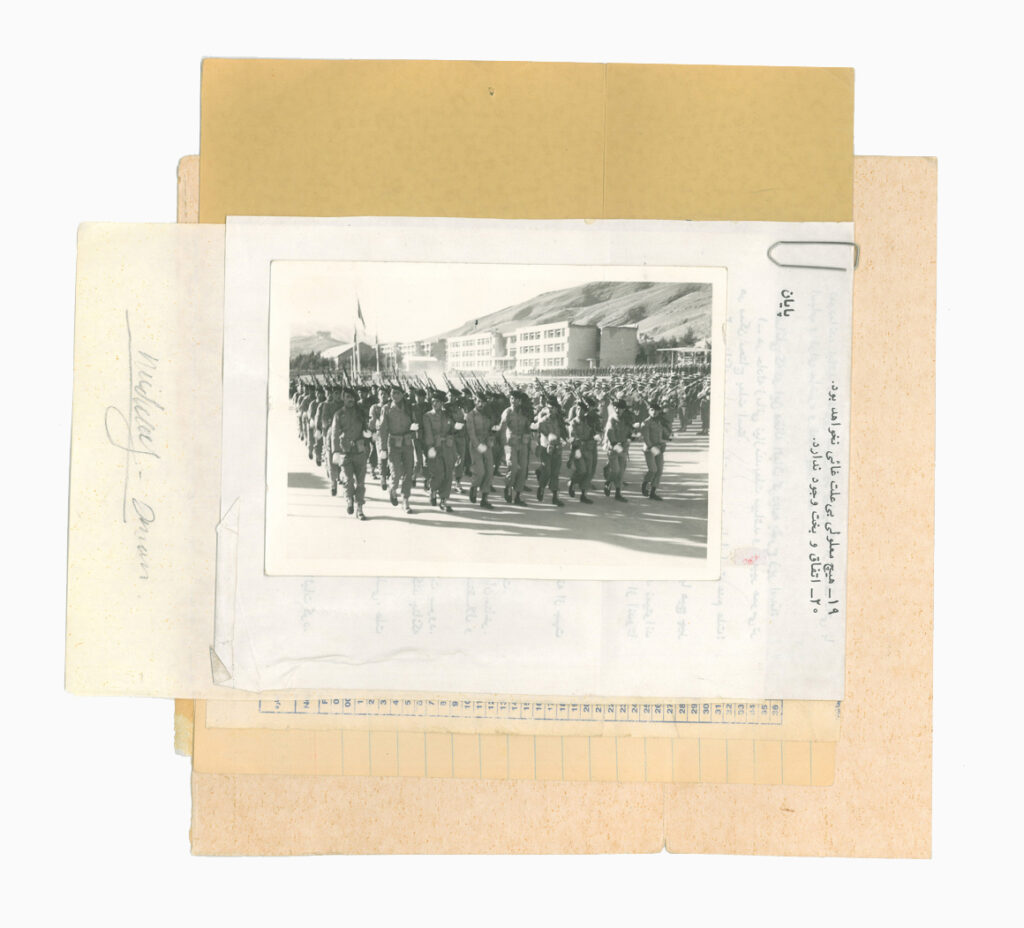

The Iranian army’s operation in Dhofar commenced discreetly, remaining absent from newspapers and the broader media until Pahlavi regime’s official declaration. At the time, the Iranian populace had limited knowledge about Oman, particularly the region of Dhofar. Consequently, at the commencement of its operation, the regime made concerted efforts to suppress any emerging information regarding the military action. Concurrently, the Omani regime also strengthened this veil of secrecy, denying the presence of the Iranian army in the conflict altogether. This synchronised approach by both Iran and Oman ensured that the events largely went unnoticed in the global media landscape.

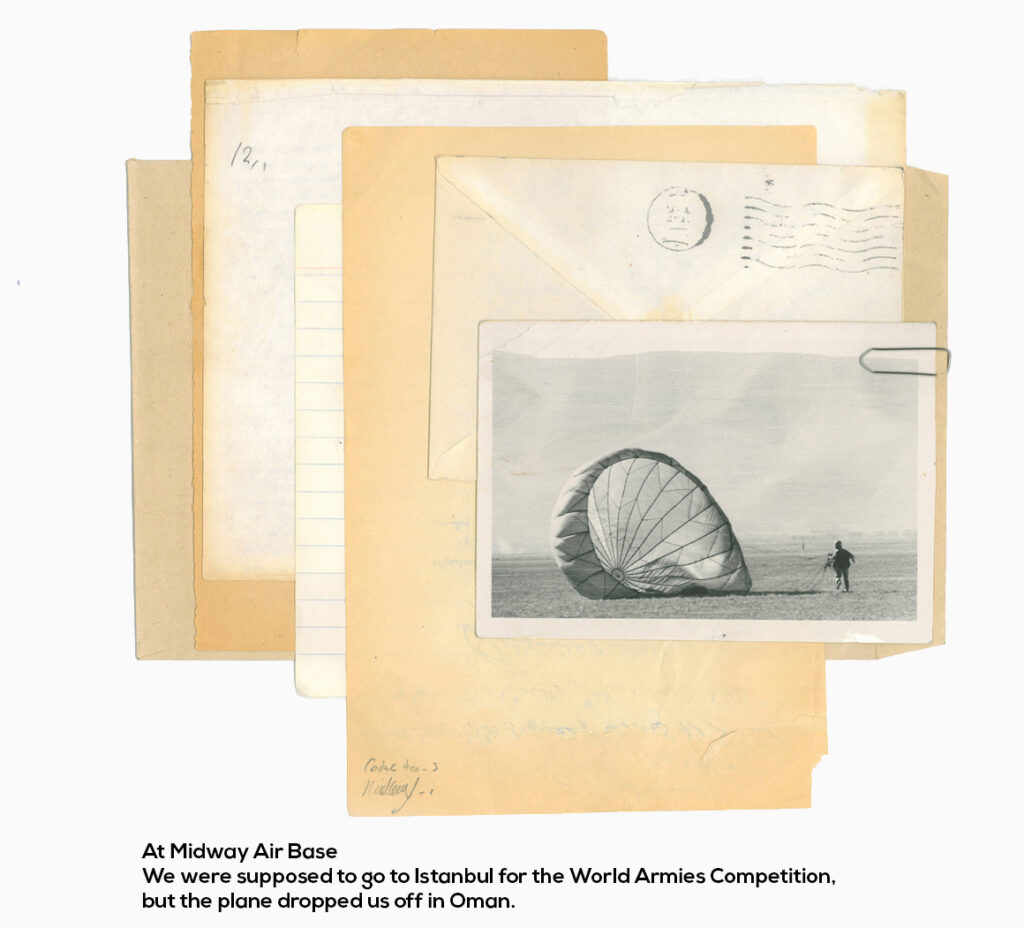

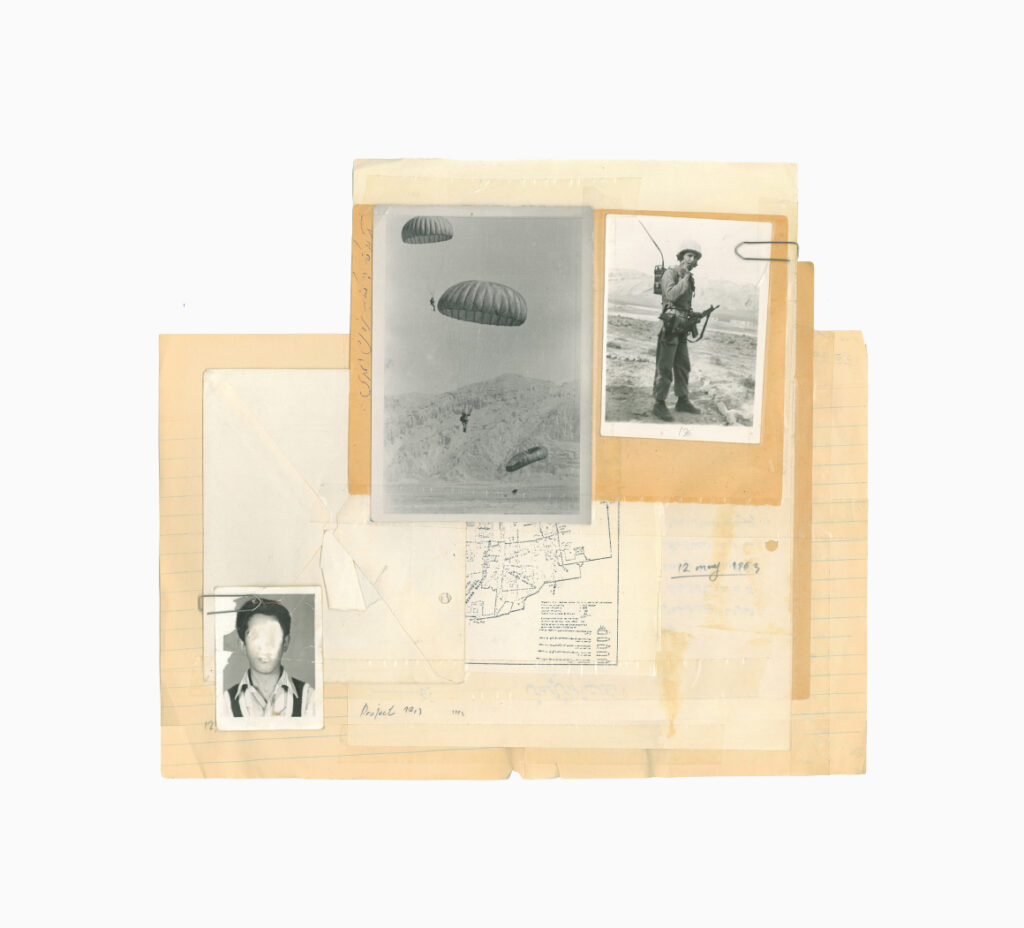

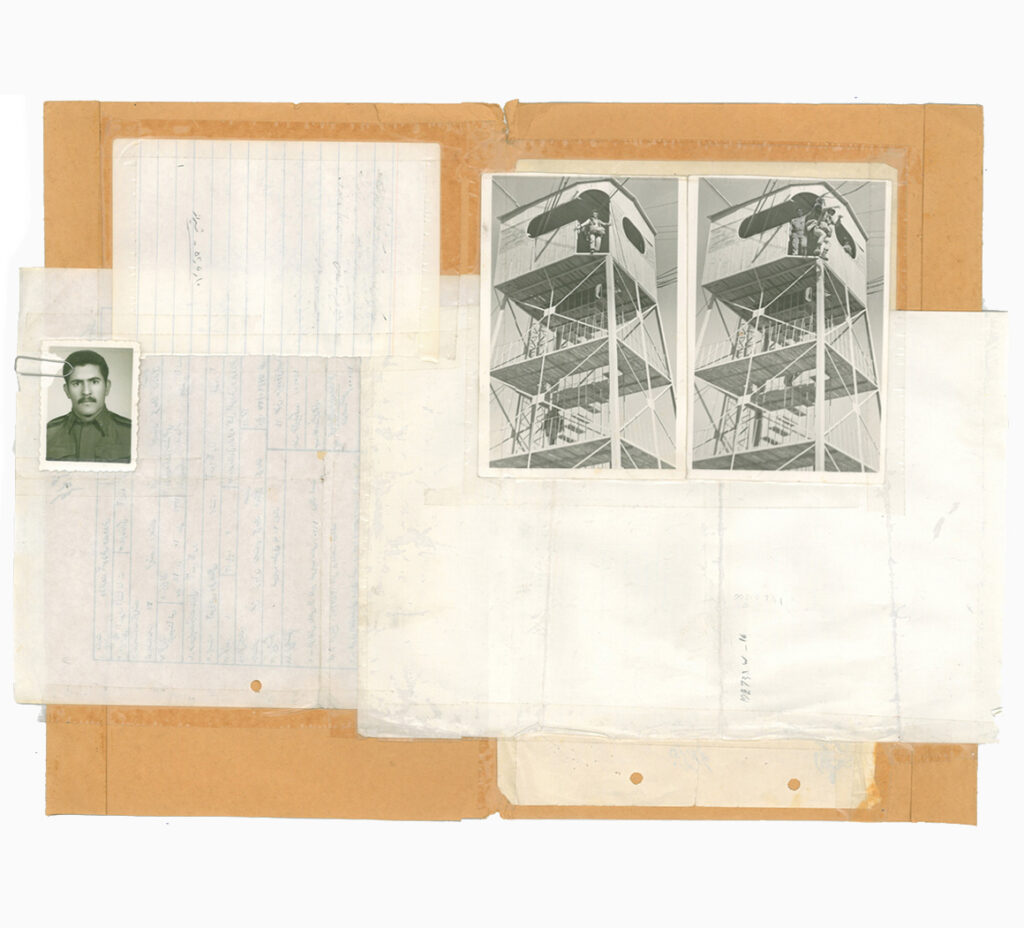

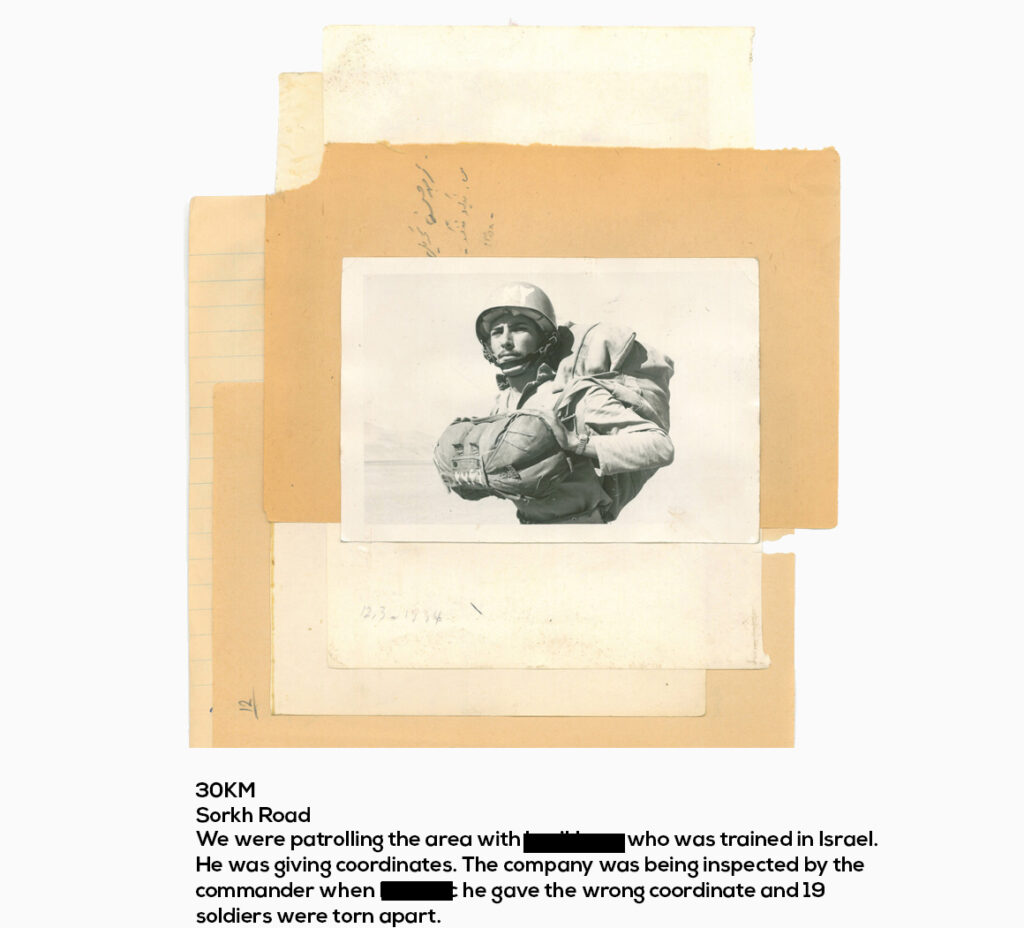

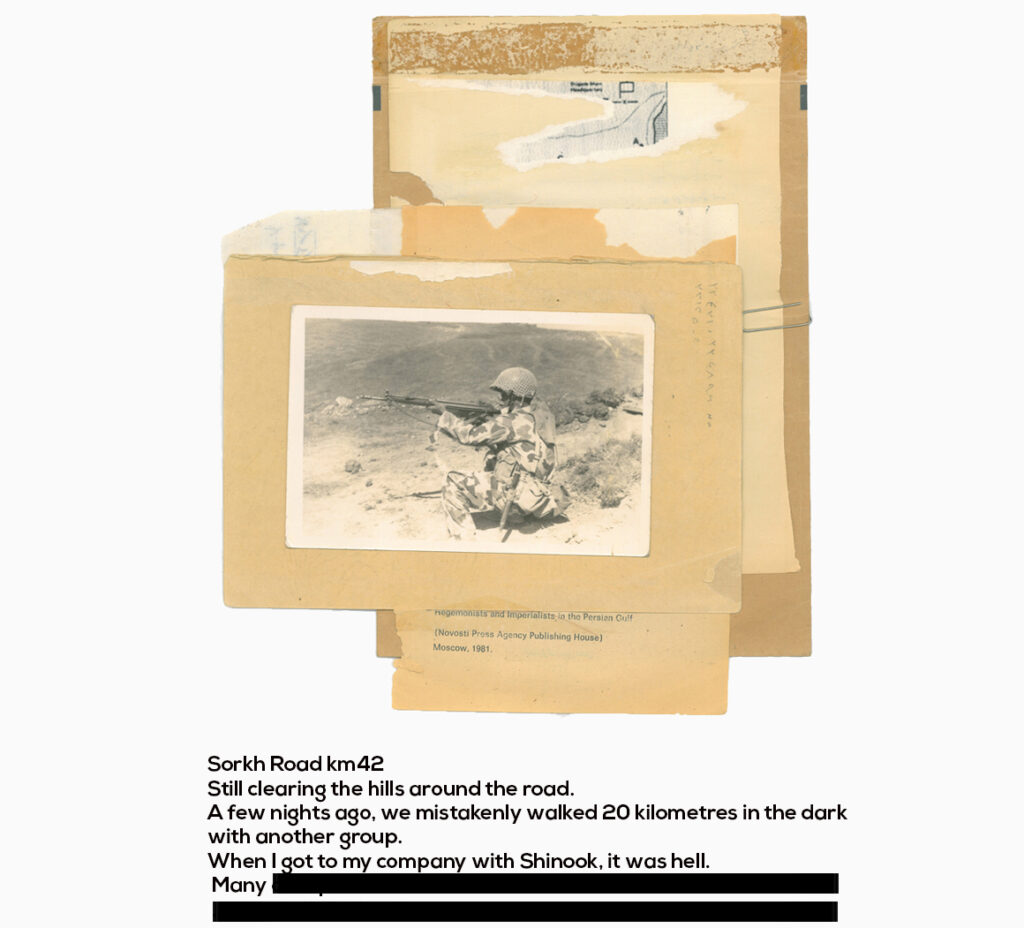

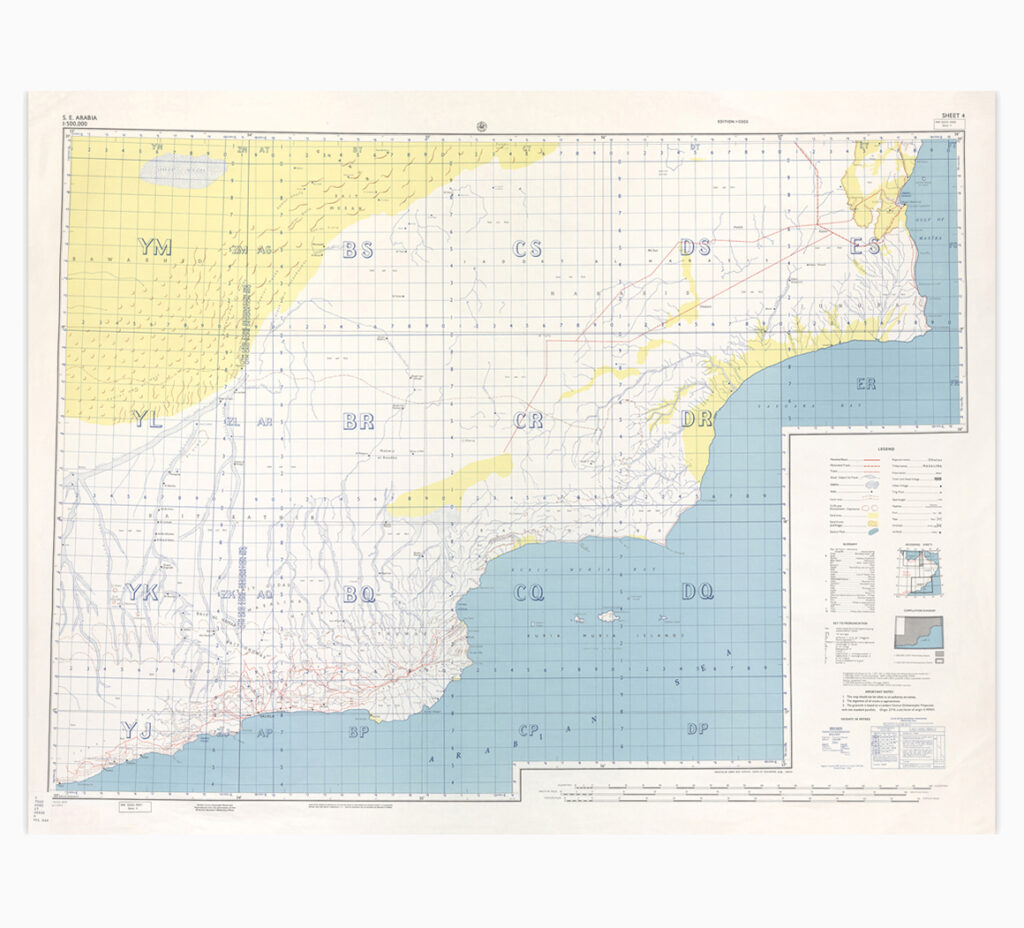

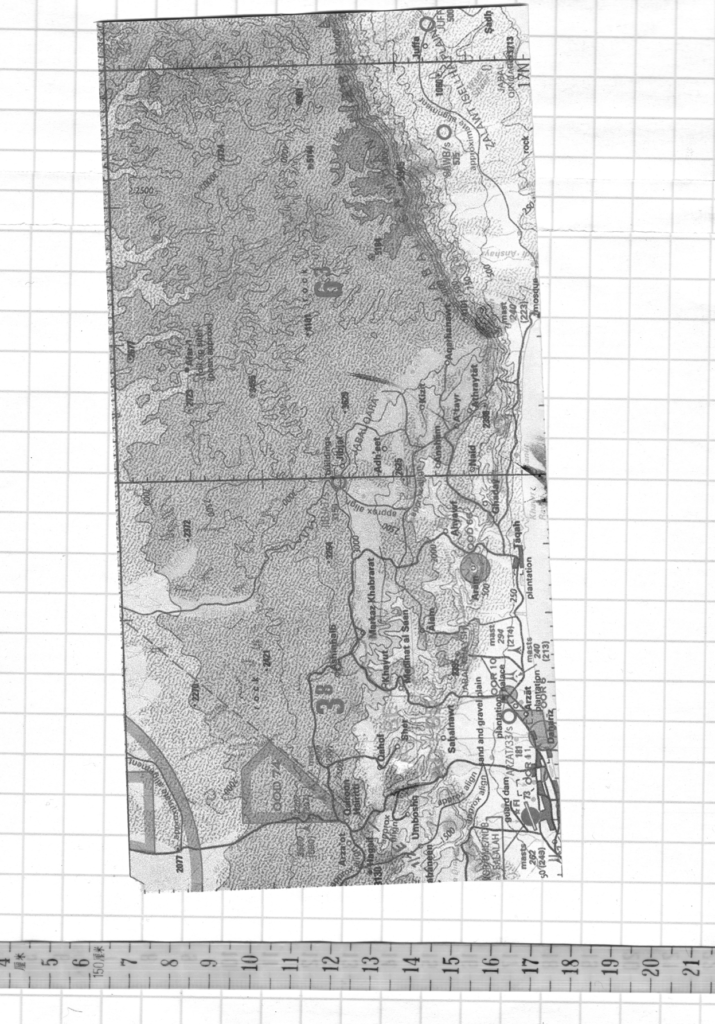

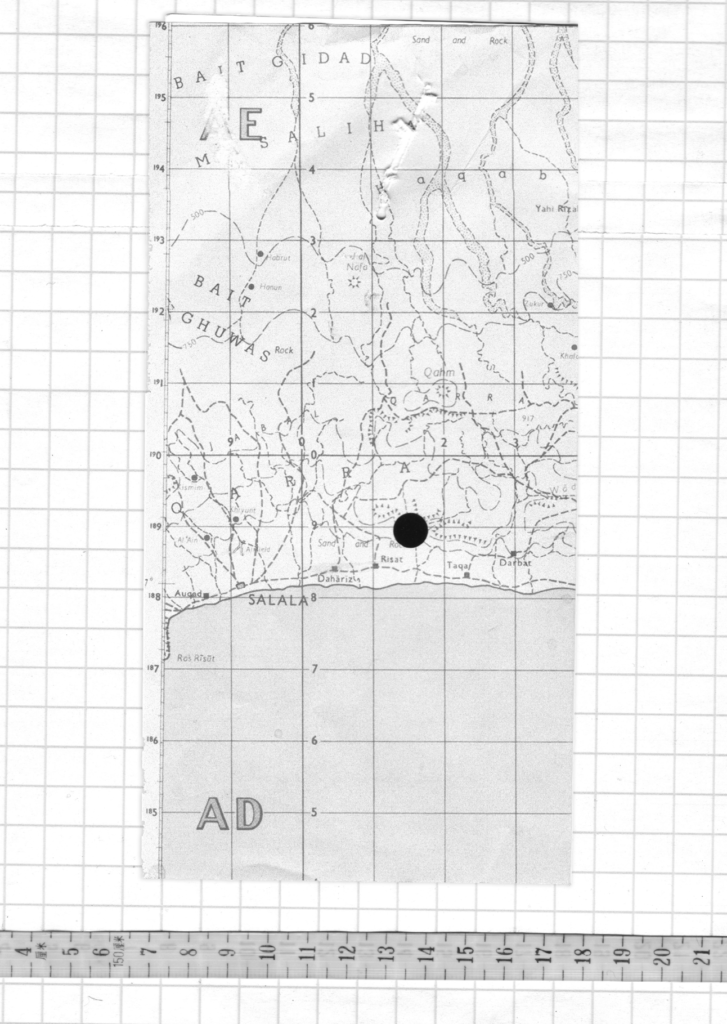

For the soldiers, the mission in Oman was merely a whisper of a rumour. Individuals were often assessed and chosen for combat in the dark and, uninformed about their destination or the purpose of their deployment, suddenly found themselves on the Omani soil. Contrary to the official narrative, many were merely fulfilling their military service obligations. The families of these soldiers were left in the dark regarding their loved ones’ whereabouts and conditions. Each military unit stationed in Dhofar operated under a single postal code for all correspondence, with the sending and receiving of communications strictly overseen by superior officers and command structures. Taking photographs was strictly forbidden. Early in the conflict, Iranian forces were clad in Omani military uniforms, occasionally even wearing them upon their return to Iran. Such was the extent of secrecy that any soldier disclosing information faced potential prosecution in military courts.

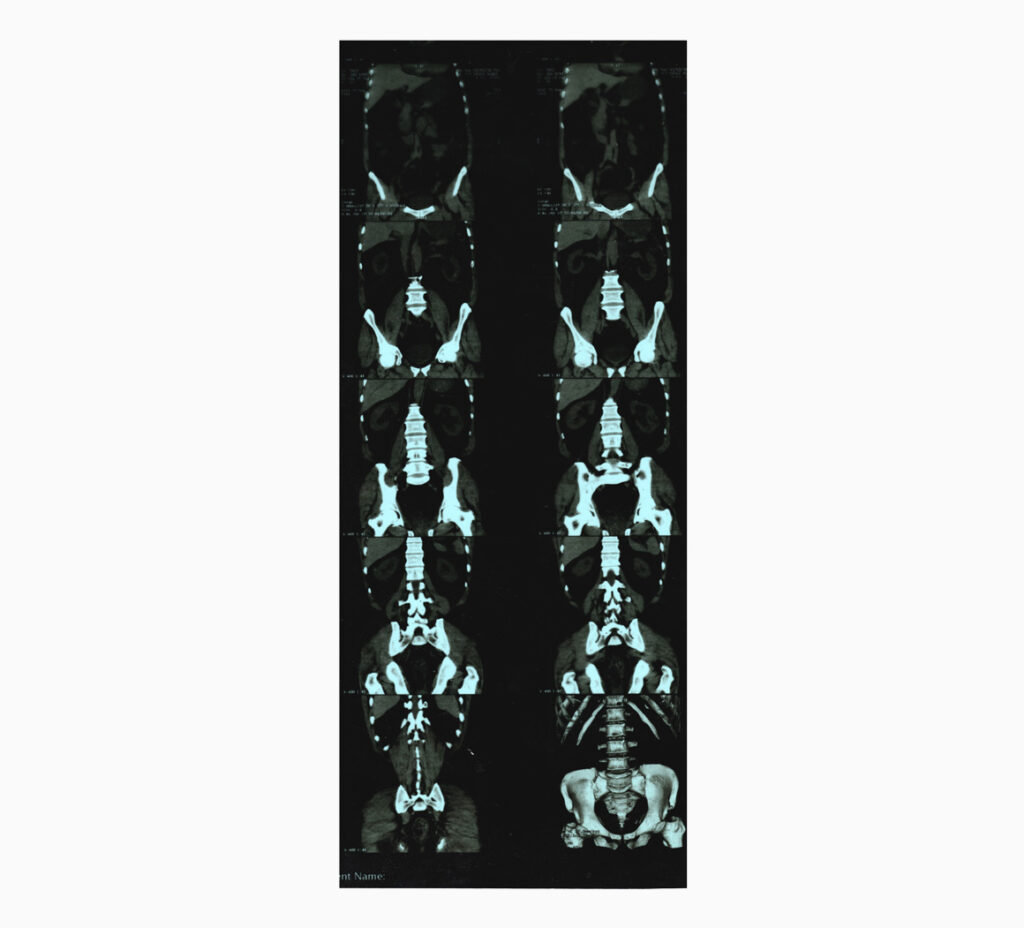

Those injured in battle were confined to a select few hospitals, all under the watchful eye of the security agency. The fallen were brought back to Iran, but there was an explicit prohibition against publicising their deaths. In some instances, the deceased were laid to rest in cities different from their birthplace, and families were denied the right to conduct independent funerals. Iran’s national radio and television remained conspicuously mute regarding the war’s casualties. This pervasive silence was echoed across various sectors, from the government to the army, the National Assembly, and the state-controlled media outlets. As a result of this widespread reticence, even today, precise figures detailing the casualties from the Pahlavi regime’s operations in Dhofar remain elusive.

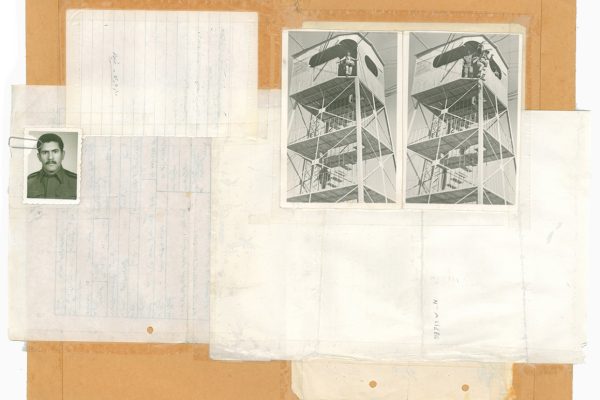

In spite of this prevailing silence, echoes of these events remain. These traces live on, not in formal documents and archives, but in the seemingly inconsequential details: letters. In this context, the notes and photographs, which might not have been intended as historical records, reveal more about the past and its events than any confidential document ever could.

Even with their imperfect and stuttering language, these letters offer the most genuine accounts of the events. Their nature is political, for they shed light on facets of history previously buried in obscurity. Letters penned solely for a familiar individual, grounded in personal connections, amplify the genuine resonances of history to a broader audience: voices unwavering in their righteousness.

“We were instructed not to talk about the war or Dhofar in our letters. There were stern warnings that breaching this directive could result in a field court martial. All our correspondences were gathered by the battalion, dispatched to a specific mailbox in Shiraz, and then forwarded to our family homes. But it seemed that these warnings where empty threats. I personally wrote a letter to my mother telling her about the melancholy of serving as a soldier far from home. I never faced any repercussions for that letter.”

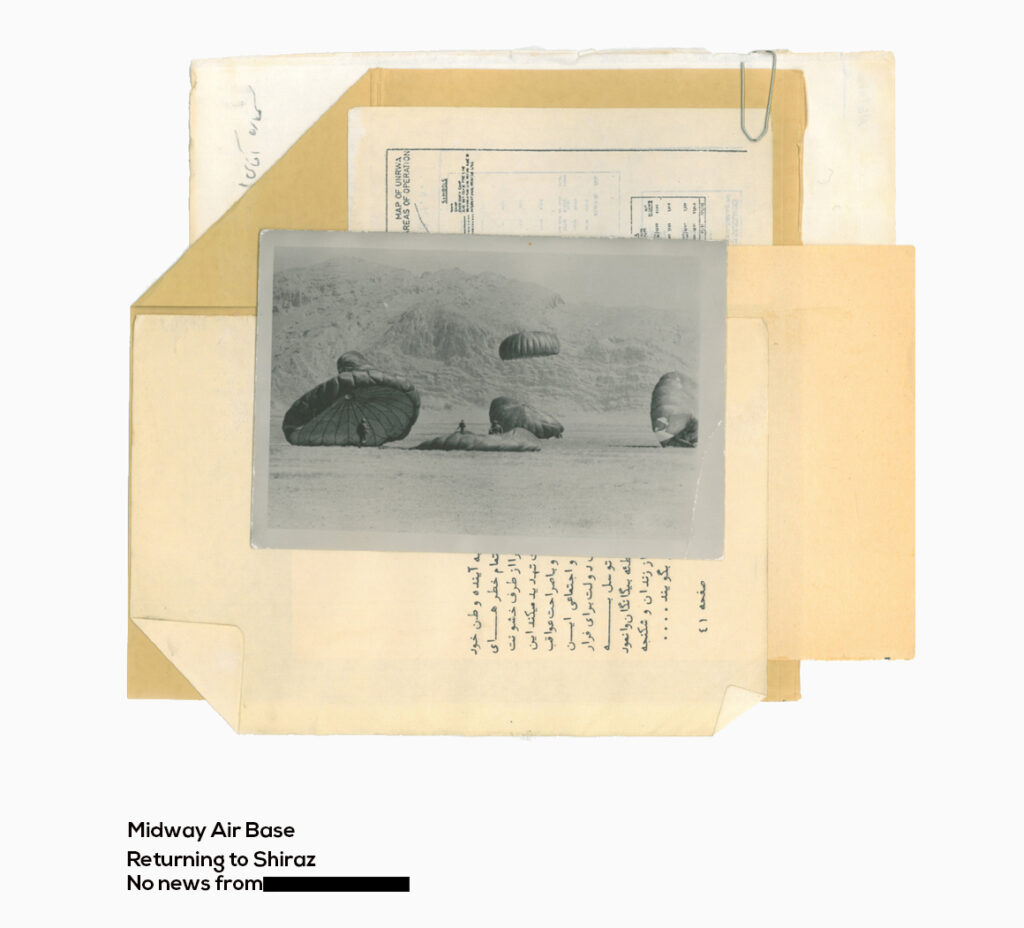

The Midway collection features keepsake photographs of my father and his fellow soldiers during their deployment to Dhofar from 1974 to 1976. Ever since I was a child, I remember my father had extreme difficulty when it came to talking about his experiences from that period. However, even his brief remarks about the photos in his album painted an image of him as a valiant ranger in my young eyes.

Years later, revisiting the photographs of the Battle of Dhofar, I recognised a discrepancy between my father’s personal narrative and the broader history I came to understand. This led me to gather photographs, letters, and recollections from his peers, hoping to uncover deeper layers of the story. The prevailing theme in these collected memories is one of significant losses, defeat, and casualties—stories that never found their way into official accounts or statistics. Their only testament lies within these personal mementoes.

In my investigation into the accessible remnants of the Dhofar events, I have recognised the profound impact of the era’s censorship and silence on its survivors. This silence manifests as an ingrained fear and hesitancy to revisit or vocalise their experiences. Perhaps what drove me to delve into this research and embark on this project was a deep-seated intrigue about my father’s apprehension, an urge to understand his reluctance to recollect and revisit a chapter of his life.