Approaching

The Marine Mansion is situated west of Istanbul’s former International Airport and accessed via the coastal road from Florya to Küçükçekmece. The building which was designed by the architect Seyfi Arkan for Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1935 was a place that I had wanted to visit for a long time and was feeling excited about seeing it. It was November and I had taken the new Istanbul-Halkalı commuter train to Florya station and walked down to the beach.

To gain access you need to first pass through the side of the compound of the Grand National Assembly’s social facilities, which felt somewhat intimidating and discordant with the idyllic images of playful families and bathers one usually associates with Florya in the 1930’s. It also struck me that the beach itself was quite small.

At the foot of the long jetty leading out to the mansion there is a hut with a watchman selling entry tickets. Outside there is a sign explaining that the Mansion belongs to the Directorate of National Palaces of Turkey. It was from this vantage point that I first came to see the building, the light was facing me so the mansion was backlit and in shade depriving me of the experience of seeing the dazzling architectural white of Arkan’s modernist masterpiece. Feeling somewhat disappointed I got my ticket and walked along the jetty up towards the building. I was reminded of a text by the anthropologist James Clifford who discusses how the experience of a place changes depending on when in its history you visit it1.

What had initially interested me in the building was the way in which it embodied an international architectural aesthetic style similar to some early Scandinavian modernist buildings, but also that it carried a specific symbolic language, one of leisure and healthy bodies in the sun, the sea, speed boats but moreover an architectural expression which was radical and new, demonstrating optimism and showing an openness to foreign influences.

Added to these fantasies I had also seen photographs and film footage of Atatürk during his visits to the mansion, rowing his boat, swimming with people in the sea or playing with children on the beach, images which are still common today and belong to Atatürk’s visual legacy. The father of the nation spending time with his subjects, people who were neither altogether accustomed to devoting their leisure time semi-naked together on the beach nor familiar with the social promises of modern architecture.

Upon entry

I entered the first section of the building, a covered walkway with what appeared to have been service quarters on the right hand side. This part of the building is more private, a rear side, the windows facing the beach are mainly from the corridor in the west wing together with a few portholes, referencing the notion of a boat or a ship. The building is in some respects two dimensional, it has a back facing the beach which is private and opaque and a front side facing the sea and sun with large windows and a boat jetty with all the guest rooms facing outwards towards the sea, somewhat reminiscent of Ottoman water baths2.

At the end of the walkway one steps directly into the main building, and as my eyes adjusted from the sunlight I saw the impressive reception room with its immense conference table and the large curved bay windows stretching around the front of the building and draped in sheer curtains which diffused the intense sunlight reflected in from the sea. Next to the modern furniture by the windows was a spectacular and very large mechanical blackboard which appeared to be motorized and able to rotate from left to right and scrolled up and down. I imagined Atatürk and his entourage using the blackboard to deliberate on the republican program. The room felt more like a seminar room rather than a reception area, a space where meetings and presentations could be held, a place for discussions and where ideas could be drawn up.

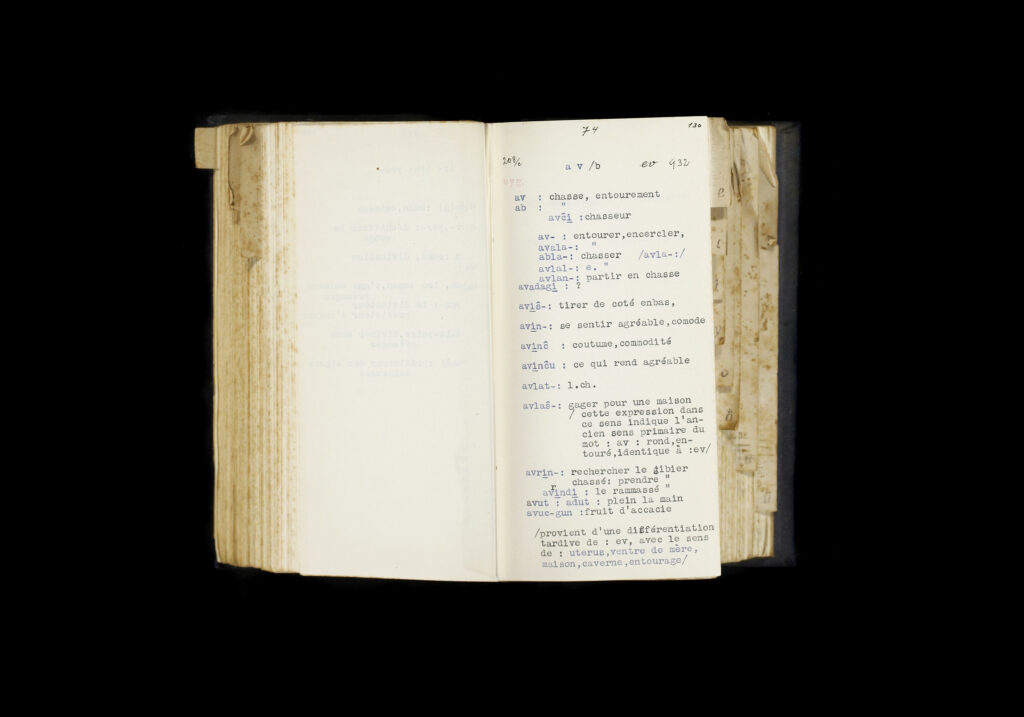

In fact during the last years of his life, Atatürk was becoming more and more interested in history and linguistics and in particular Sun Language Theory, a refuted hypothesis introduced by the Viennese linguist and Orientalist Hermann Feodor Kvergiç, which proposed that all human languages are descendants of one proto-Turkic primal language3. The summer mansion could very well have been one of the places where such discussions were held. Some evidence of this can be found to the left of the reception hall in Atatürk’s office where there is a black and white photograph depicting a meeting in the same room in 1937 with the Swiss anthropologist Eugene Pittard together with Ayşe Afet İnan, one of Atatürk’s adopted daughters. İnan was a PhD student of Pittard at the time and a sociologist and historian known for having measured hundreds of thousands of skulls in Anatolia in the 1930´s in search of a unifying Turkish history4. At a time of rapid modernization and in the seismic shift from late Ottoman Turkey to the new republic, Atatürk was in need of historical legitimacy. According to linguist Ghil’ad Zuckermann it is also possible that Atatürks interest in Sun Language Theory was a way to side step the shortcomings of the Turkish language reform and legitimizevthe many Arabic and Persian words which the Turkish language authorities had not been able to do away with5.

Moving through

I continued on through the building via the obligatory map of info-points staked out by the audio guide. The guide itself was a bit of a nuisance and got in the way of the spontaneous and physical and spatial experience of the rooms, so not wanting my first impressions to be clouded by official museological explanations I concentrated instead on trying to experience the space and taking some snapshots with my iPhone.

The light that day was really quite beautiful with the sea glistening behind the sheer curtains, perfect for the architectural performativity of the building. As soon as I entered it became obvious to me that I had stepped into a staged enactment of ideas, a form of propaganda representing a new republican modernist dream. Buildings that embody an ideological or philosophical positioning or gesturing often become interesting when displaced by time. The building seen as a relic of an idea. What also interested me was the distance that these gestures represented in the light of a very different Turkey today, post Gezi Park protests, religious populism and President Erdogan.

Moving through Atatürk’s living quarters, trying to avoid the ribbons and ropes strung up between the visitors and the furniture, I peered into the large bathroom, with its peculiar weighing chair, apparently used for the doctors to keep an eye on Atatürk’s deteriorating health. I also passed a small room which contained a bed and what would have probably been Atatürk’s chaise longue. Most of the furniture and light fittings in the mansion were designed by Arkan, something which was typical for architects at the time as there was no generic furniture to go with such modern buildings and was part of the mission to create a complete environment, to perform the modern dramaturgy of the space. The furniture and lighting was subtle, simple and practical.

Leaving the living quarters I proceeded down the corridor of the west wing, looking in on each of the guest rooms. It was clear that the rooms had been arranged and reinstalled to appear as they might have looked during Atatürk’s time at the mansion. Interspersed with the rooms in the corridor there are some glass cabinets containing artifacts connected to Atatürk such as his bathing slippers, bathrobe and bathing trunks, presumably brought back to the site when it was turned into a museum. One particular item which stood out was the silver belt buckle on Atatürk’s bathing trunks which depicted a naked figure athletically diving into the sea. The design had a sense of Art Nouveau about it and reminded me of early twentieth century depictions of healthy bodies exercising, doing sports and becoming strong and vigorous subjects for their nation state.

The mansion was obviously intended as a spectacle and a place which could be mediated. Arkan’s design for the mansion underscored that this project was a testimony to the idea that the Republican revolution was the people’s revolution and that this was a place where the nation and its leader could come together. Newspapers and newsreels at the time often depicted and reported on Atatürk’s leisure time at Florya and his encounters with his people, rowing his boat and swimming: ”The most democratic president in the world who cruises in a rowboat among the masses”6. The walls of the mansion are covered with such images including several iconic photographs of Atatürk with Ülkü Adatepe the youngest of his eight adopted daughters. In the photographs and newsreels we see them taking walks together on the beach promenade, learning to write on the blackboard or the little girl being disobedient lying on the ground outside while Atatürk even-temperedly looks on. The patient father of a young nation?

Walking back through the covered walkway, I discovered another room which contained Atatürk’s rowing boat and more photographs of him in the sea. At the end of the walkway there is a small room which I had missed on my arrival containing a tiny exhibition about Seyfi Arkan, a few photographs and documents including a letter from the municipality to Arkan confirming the completion of the mansion. It was a small and non-conclusive presentation but one which at least acknowledged the artist behind the work, like a tag or a signature to the building.

Exit

Leaving the mansion and walking back over the jetty to the beach I remember feeling exhilarated about having experienced the building’s performativity, even in its subjugated state as a museum. However another more curious feeling followed me that day, the overhanging question why the modernist promise embodied in the mansion was never really fulfilled. At least not in the way it had in many European countries where similar architectural prototypes came to form the basis for a more structural and social modernist program7.

Seen in parallel with Atatürk’s interest in Turkic origins and linguistics at the time and his attempts to find a national consciousness made me also think that the gestures embodied in the building might have originally fulfilled another more ambiguous agenda, something which both signaled an understanding of international movements and interactions with Europe, but at the same time something which turned inwards, towards the Turkish people, giving a pledge of what could be attained by the republic even if this was something that was far out of reach of most everyday people.

Wanting to linger a little while longer on these thoughts I stopped for a coffee in a nearby restaurant. Sitting in the bright empty dining hall looking out over at the sea and the Mansion off-season in November imparted a peculiar sense of loss and underscored the feeling of having just witnessed the relic of a promise which was never truly realized.

With acknowledgments and thanks to Esra Akcan, Bernt Brendemoen, Olof Heilo, Jens Peter Laut and Seher Uysal.

A version of this text was first published in Swedish in Ord&Bild no. 3–4 2023, “Istanbul – Staden som palimpsest” and later in English in Dragomanen 26/2024, “Pedestrian Modernities Blind Spots in Turkish Cultural Heritage“.

- Clifford, James: “Routes – Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century”, Havard University Press, 1993. ↩︎

- Dergisi, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 25–49, 2005. Akcan, Esra: “Ambiguities Of Transparency And Privacy In Seyfi Arkan’s Houses For The Turkish Republic,” ODTÜ Mimarlık Fakültesi ↩︎

- Aytürk, İlker: “H. F. Kvergić and the Sun-Language Theory”, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Harrassowitz

Verlag, 2009.

↩︎ - https://dbpedia.org/page/Afet_İnan ↩︎

- Zuckermann, Ghil’ad: ‘‘Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew’’, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan,

ISBN 1-4039-1723-X, p. 165, 2003. ↩︎ - Akcan, Esra: “Ambiguities Of Transparency And Privacy In Seyfi Arkan’s Houses For The Turkish Republic,” ODTÜ Mimarlık Fakültesi

Dergisi, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 25–49, 2005. ↩︎ - Mattsson, Helena; Wallenstein, Sven Olof: “Swedish Modernism: Architecture, Consumption and the Welfare State”, London: Black

Dog Publishing, 2010. ↩︎