An Interview with Zobair Movahhed

Zobair Movahhed is a mathematics teacher from Khash in Sistan and Baluchestan. He is also a photographer. The subjects he chooses—drought, migration—are deeply tied to his life and lived experience. In his collection The Migrants (2021), he traces the journey of Afghan migrants crossing the border, accompanying them along their path. To get close to people in such dire circumstances—where the air is thick with the scent of death—requires adjusting one’s pace and presence to the other. Zobair has managed to do precisely that.

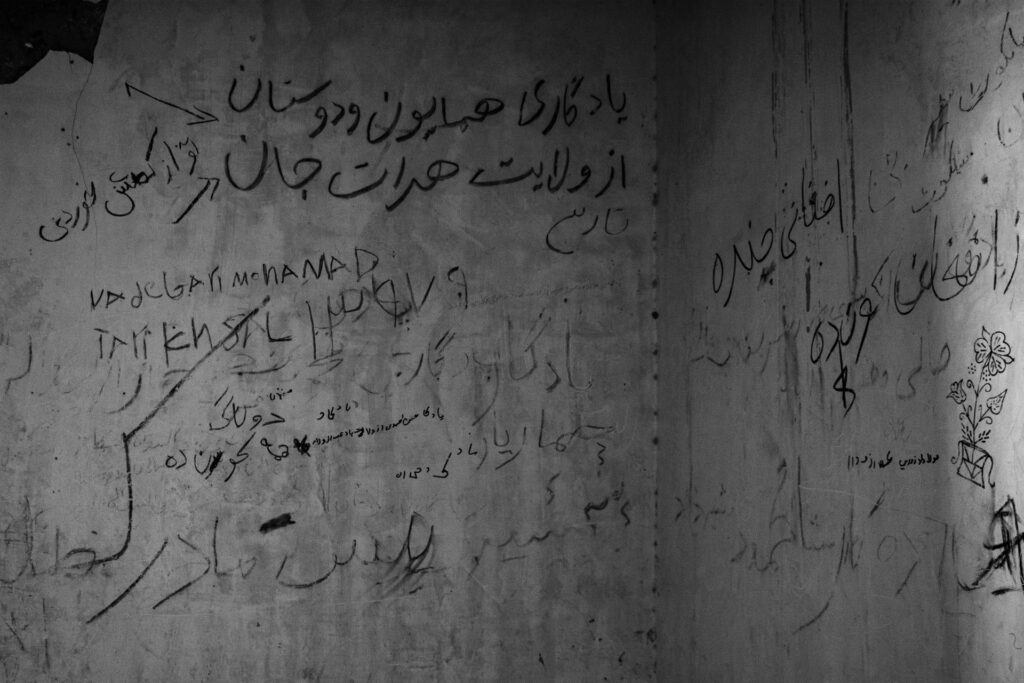

Yet, he has not lost sight of photography itself. Moments of togetherness and solitude both feature in his work. His perspective invites us to witness the everyday subtleties of the journey: walking, resting, eating, sleeping, praying, showing kindness, and being crammed into the trunk of a car. Images of identification papers, meagre food portions, handwriting on the walls of temporary shelters, and beads of sweat on a forehead all attest to his meticulous attention to detail. However, the significance of these photographs cannot be reduced to mere documentation of unseen realities. Their formal composition and artistic quality stand on their own. Zobair’s snapshots capture the affective dimensions of the journey, demonstrating how he balances an intimate approach with a necessary distance.

In 2023, Zobair published a selection of these photographs as a book in collaboration with Baradar Books. In this publication, he interweaves images with passages reflecting on the journey and his dialogues with fellow travellers, revealing hidden aspects of this forced migration. It is a story of departure, exile, and separation from loved ones. What better title for such a book than The Journey of Separation?

Below, you can read selected excerpts from Safar-e Hijr, followed by an interview conducted by Sarazad with Zobair on the occasion of the book’s publication.

“For those who have chosen emigration, illegal passage across borders is the quickest and yet most dangerous way to reach their destination. This story is only a glimpse of the sorrowful journey that these travellers embark on in spite of their little chance for survival and success.”

“Terror, hunger, humiliation, and beatings inflicted by the smugglers or officers are common on this twenty-day journey. Omid, the son of one of the smugglers, prepared the immigrants to get in a car by using vulgar language and swearwords. A smuggler beat an immigrant and made him, who was physically stronger, take off his leather coat just because he liked it. The immigrant’s slight resistance led to his being locked up for two weeks.”

“Ayyub was an immigrant who had left his bride just six days after their marriage. Zakir had to leave his home one month after his brother and father were brutally murdered by the Taliban. They both said that terror, insecurity, and unemployment had besieged them and their families. They had no choice but to make the journey. They believed that it would have been better for them to stay in Afghanistan if they had a job which could enable them to provide for their families.”

Sarazad: Zobair, thank you for accepting our invitation to share your thoughts and work with us. Let’s begin with an essential question: what inspired this series? Before you started photographing migrants, did you engage in any research on migration and Afghan communities? Or was your focus shaped by personal experiences?

Zobair: When I was a child in Iranshahr during the 1970s, many Afghan immigrants had fled to our area to escape the Soviet war. They came because we shared similar clothing, religion, and language. My father owned a rice shop and hired one of these immigrants, Ghulam Sakhi, who had come to Iran with his children. We were in touch with each other and we became friends with his children.

Balouch and Afghan people have had a connection with each other ever since. In fact, we have been directly involved with the issue of migration. We knew migrants as well as smugglers. There were occasions when some people we knew would get hit by cars that we called Afghan kesh and die. These were the issues that we had to deal with back then and they are still our issues today.

These issues have stayed with me from the onset of my photography practice. How is it when a Toyota pickup truck, carrying twenty-five passengers, speeds past you at 200 kilometres per hour? Imagine how people perch on the edges, one foot inside, the other dangling out. You cannot help but ask: why? Why must anyone endure such conditions? These thoughts lingered in my mind until I started this project. As I am from the area and know the people and they know me, it was a bit easier for me to access these environments and photograph them compared to others.

Sarazad: Were these topics what inspired you to take photography more seriously or had you already developed an interest in photos and photography before that?

Zobair: When my brother and I were in high school, we had a camera and often took pictures of ourselves. Photography was fun for me back then, but I began pursuing it seriously around 2016. I started with nature photography, but it did not resonate with me. I found people interesting. When I look at old photos, I enjoy examining the details—people’s clothes, hairstyles, the space around them, and the overall environment.

So, I gravitated toward social documentary photography. I was set in Zahedan and I really loved taking portraits of ordinary people on the streets. I started working on a collection on the topic of religion, but I had to leave it halfway because of the circumstances. I also documented the drought in Zabol for a while. This collection, however, began in January 2018 and took about three years to complete. There were times when I photographed for several consecutive days and other times when I would not take a single shot for three or four months.

Sarazad: How did you build your relationship with the immigrants and how was it maintained over time? From the photos, it seems a genuine friendship developed between you. What factors contributed to this bond?

Zobair: One factor is that Afghan people are very approachable and open. They are not reserved, and anyone who wants to get into their crowd can do so easily. Afghans are naturally friendly and form bonds quickly. For instance, photographing women and children was challenging due to cultural restrictions, but the issue resolved itself easier than I thought and and over time, some people allowed me to photograph their women and children. The number of women and children was of course very limited. Out of every seventy people, only three or four were accompanied by their families. Most were alone, had sent their women and children before, or had left them behind in Afghanistan.

Another factor is the nature of migration as condition. Typically, the journey involves several major smugglers who manage different segments of the route. For instance, a smuggler might promise to take someone from Nimrouz to Tehran for a fee of two million, guaranteeing safe passage. However, the journey is fragmented, with different people handling each leg.

One smuggler might be responsible for the route from Nimroz to Pakistan, another for crossing the border, someone else for the journey from the border to Kerman, and yet another for the stretch from Kerman to Tehran. Along the way, migrants are often taken to rest areas where they have to wait for the next ride. The waiting time varies—some times it is three or four hours and other times it might last three or four days. At times, it might take a week to ten days before the next car arrives.

My first photos were taken inside these resting stations. I did not use to take any pictures at first; I simply sat with people. We talked, prayed, and shared meals. I was also interesting for them and the more we had to wait, the closer we grew. As we spent more time together, my presence became less noticeable.

Hardships of their journey should also not be dismissed. When you approach someone who had been stuck for twelve to fifteen hours in the back trunk of the car with four others and empathise with them, they start to wear their heart on the sleeve and a connection naturally forms.

Sarazad: Could you share more about the emotional experiences of immigrants who often travel alone, leaving behind their homes and families? How do they express and cope with such emotions during their journey?

Zobair: Leaving one’s family behind is an incredibly difficult emotional experience. Over the three years I worked on this project, it was very rare for me to see the same person twice. Perhaps it only happened once. But I often ask people about this issue the first time I met them: Why do you have to do this? What needs to happen for you to decide to stay? I heard a variation of a similar responses from many: “If I had a job that could support my family and let me sleep peacefully at night, I would be mad to go through all this.”

Sarazad: In the text accompanying your photos, you mention someone called Ayoub and talk about his life. This focus on the individual and the specifics is compelling and provides the audience with diverse perspectives. Highlighting a name and a personal story sets you apart from the cliché generalizations about the nameless immigrant and reflects a distinct artistic approach. Was Ayoub the only individual whose life you engaged with or were there others as well? If so, why were their stories omitted?

Zobair: Ayoub was not the only one. There were other people whose lives I heard details about. Some moments stand out in my mind. We always ate together, but one or two occasions have been engraved in my mind. The memories and conditions people tell you about are so moving that they stay with you. For example, there was the story of this baby who had arrived at Iranshahr when it was eighteen days old. The family was on the road for ten days. I kept thinking that this woman had set off on foot with her children five or six days after giving birth and had walked in the mountains for twenty-four hours nonstop.

There was also the story of Ayoub who had set off on the journey just a few days after getting married. I compared myself to him. How can you leave your wife three or four days after getting married? A person has dreams for their marriage. There were many cases that I did not write about. It was mostly selective. I believe that a photographer should speak his mind through his photos.

Sarazad: Could you tell us more about the geographical settings of your photographs? Did you plan the locations in advance or were they chosen spontaneously along the way?

Zobair: The photographs can be divided into three geographical categories: the border, resting stations, and Tehran city. There are also a few photos taken inside homes in Tehran. I wanted my collection to cover the entirety of the route from Nimrooz to Istanbul. But it eventually did not go further than Tehran. Despite prior arrangements, in Tehran, I was not able to get hold of the people whom I had met earlier and whose numbers I had. So, I had to contend myself with taking photographs of the immigrants I encountered on the streets. Street photography sometimes puts people off and is different from photographing people you have spent time with and talked to. Afghan people in Tehran are, in particular, in a vulnerable position and often fear that I might be connected to the government and cause trouble for them. Making connection with people was more challenging for me in Tehran and I was not able to work there much. Of course, I did not put all that I had in it eighter.

Sarazad: Could you share more about the hardships people face at the border?

Zobair: The Kohak border is in a mountainous area, so the border wall has not yet reached that region. The border there is either marked by barbed wire or mines. The local people know the area. So, taking photographs at the border is not really possible and is rife with fear and trouble. Most migrants travel on foot during the night and reach their destinations by the morning. I was only able to take photos along the border in the early hours of the morning.

Sarazad: What led you to choose black and white for the photos in this collection?

Zobair: The environment itself is devoid of colour. If the photos had been in colour, the intensity of the surroundings would not have been conveyed as effectively. Colour tends to create a more uplifting and open atmosphere, whereas black and white better highlights the form and the weight of the environment.

Sarazad: What was your process for selecting the photos in this collection?

Zobair: I did not select the photos myself. Two photographers with experience of working in Afghanistan and Sistan and Baluchestan chose the photos in two stages. I simply took the photos.

Emotionally, a photographer tends to favour some photos over others, which is why I believe an outside perspective can be more level-headed in selecting the final images. Of course, we discussed the choices together and came to a shared understanding.

The photos in the book represent only a portion of the collection. Out of more than two thousand photos I had taken, around one hundred and eighty were selected. The publisher also was in charge of selecting the images for the book and I was not involved in that process.

Sarazad: Do you think there was a way to approach this collection differently, perhaps in a way that would have given the photos a greater sense of life?

Zobair: There is no trace of life in my photos—everything is about death. How can I show life when I did not witness any trace of it? The environment and conditions were extremely harsh. I did not want to depict hope in these circumstances. I aimed to show what I saw. When I encounter hunger, thirst, and humiliation, I cannot portray hope in such an environment. Generally speaking, when there is no hope, I cannot display it.