Maryam Ahmadi, Anahita Anaseri, Fatemeh Attaran, Sonia Borj, Zoya Gholizadeh, Sareh Raissianzadeh, Mansa Sabaghian, Naghmeh Yazdanpanah

Nazly Pourshirmohamad (1981, Tehran) has worked in the field of sculpture and installation. She has been working on an artistic research project named I, Nazli, My father’s Son. She explores the various hidden and manifest aspects of her relationship with her father and the effects of this relationship on her life. Her inquiry gradually led her to gender studies and in time her work aquires autoethnographic and collective traits. This text is the product of a coauthorship process in which Nazli’s narrative becomes interwoven into the stories of her colleagues.

When He Counted Me as Human, I Was on Cloud Nine

My earliest memory of being recognised through art goes back to when I was four or five. I drew a picture of a turtle and Mom and Dad proudly showed it to everyone who came to our house. I loved the attention and the approval. Perhaps that was when I decided to be an artist.

In 2013, after sculpting for two to three years, I started a path that I am still on. Aria Iqbal, the founder of Aria Art Gallery and School, suggested that I joined Behzad Khosravi’s “Public Art and Publicity of Art” course. I first thought that we are going to discuss issues relating to urban arts, like urban sculptures and art in public spaces, but during the first session in Aria School’s basement, I realised that there was much more to explore. Even though I had to struggle with unfamiliar terms and concepts, I found the subject so captivating that I continued into the second semester, hoping to learn more through hands-on projects. Practical work has always been my kind of work.

At the start of the class project, I started to look into the journey that I had taken to where I was and who I had become: how did Nazli, who had studied industrial design, dropped out of university in the final semester and later explored sculpture and visual arts, reach this point? Thinking about my life’s events and significant memories always took me back to my dad.

I was a girl who enjoyed technical and “masculine” activities, crazy for taking gadgets apart and exploring how they worked. Sometimes, Dad would bring home stuff like blueprints and machine parts from work and I was enchanted by them. Once, when things had gotten tough at work, we helped him assemble a snake and whirligig toy. I was so proud of myself! And maybe that is why I remember that toy, but my brother does not.

I remember every step of the work. First, I would put the metal tip of the curler through a hole in the plastic piece beneath it. Next, I placed a dark brown magnet that I had cut before onto the metal part. Then, I only had to fix the upper plastic part of the curler in the lower part and voila! When you turned the wheel on the narrow groove cut through the body of the twisting metal snake, the snake would crawl back and forth on any surface.

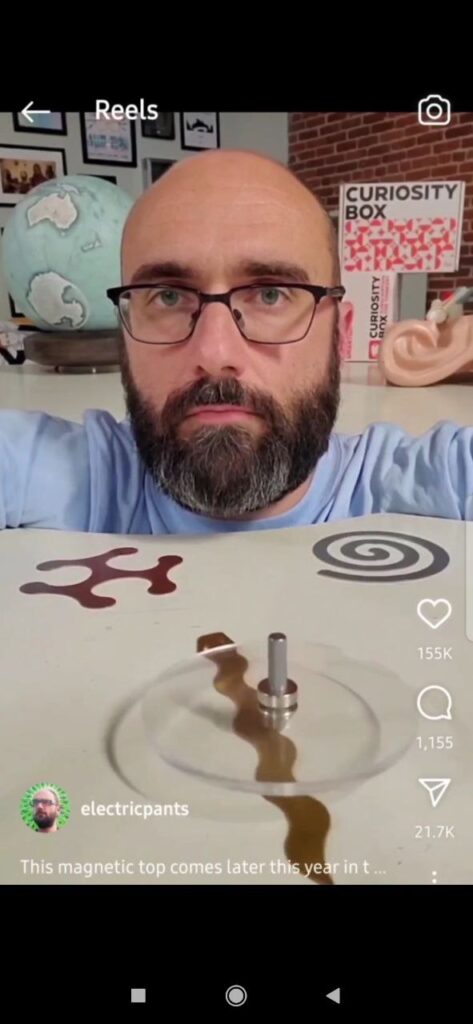

Recently, a friend sent me a post on Instagram about a man who had made a similar toy and was proudly announcing its launch. I wrote back, “My dad made something like this when my brother and I were little, but his was actually cooler.” The friend replied, “It’s funny that it made me think of you, then. I thought you’d like it.” Had I liked it? I was ecstatic. We do not have any of the snake whirligigs that we assembled, but now I at least have a short film to show people if I want to talk about it.

The times when we went to Baba’s moulding and plastic injection workshop were incredible. He would eagerly explain what he did and how the plastic injection machine worked and I was mesmerized. I learned many of the jargons. The scent of steel, grease, hot plastic, tools, and metal parts transported me to another world.

Fatemeh: I identify with Nazly and her project because it hits close to home for me. My father used to spend a lot of time with my sisters and me and, frankly, it was fun. More than hanging around my mother in the kitchen and her study room, we spent most of our time around my father and his tools, thinking to ourselves that we are helping him repair a bicycle or the television or build a wooden desk. When he asked for my help and counted me as human, I was on cloud nine.

Maryam: Thanks to my father, I began reading and writing at an early age. He used to buy us the finest children’s books from Tehran, and we always saw him and my mother engrossed in reading. From the very first grade, I used to devour all those books in a single day. My library membership at the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Adolescents, our extensive library at home and secretly reading adult books became a big part of my life. By the time I was in the second grade, they had dubbed me “Ms studious.”

Dad used to design his products in his head and then he would sketch their plans and make their moulds. Watching the transition of those flat shapes on paper to three-dimensional negative objects and then seeing the molten plastic flow into the moulds to form the positive three-dimensional final product fascinated me. It captivated me so much that imagining the multiview projection and negative mould of objects turned into a mental game for me. By the time I finished high school, I had gotten more into drawing and painting, but even then my mental world was that of three-dimensional mass and I made sense of most academic subjects with a three-dimensional mindset.

Anahita: I have known Nazly since 2011 when the course of my life had pushed me to resume my studies in the field of industrial design. When I found out that Nazly’s major is the same and that she is into sculpting, her friendly and pleasant personality became even more appealing to me. We went out to buy sculpting supplies a few times and there she told me the story of her father’s trip to Japan and many other fascinating things that had fuelled her passion to pursue this field.

In the second semester of the “Public Art and Publicity of Art” course, I shared the vivid childhood memory with the class in order to start my personal project. Around 1988, Baba went to Japan on a multipurpose trip. When he returned, he told the seven or eight-year-old me about a big factory he had visited there. Baba said, “Can you guess who earned the most in that factory? A man who had a suite all to himself on the factory’s top floor. The suite had everything—TV, sofa, bed, you name it. And he could come and go as he pleased. He slept, watched TV and worked whenever he wanted. Do you know what he did? He designed the things that the factory produced.”

A few years later, I watched a TV series about a boy preparing for the nation-wide university entrance exam who had to choose his major. That was when I first realized that this fiend, my father’s field, was called industrial design. I sat for the art entrance exam. I needed a higher national score to be accepted for industrial design in state universities, but I performed well enough in the theoretical exam to get into graphic and sculpture programs at any state university. When I found out that I was accepted in the Industrial Design program at the non-governmental Azad University, I did not even attend the practical exam for the other majors, even though my professor had assured me that I could get into the best state art schools for sculpture. I told my parents that I had failed the state university practical exam and finally enrolled in the Azad University Industrial Design program. Deep down, I always wanted to be my dad’s son.

Naghmeh: I always thought I was daddy’s girl, which is strange because my father had quite a temper and was quite at a loss about what to do with this “girl” of his. He recounts that when I was born, he was less than happy to find out that the second child had again turned out to be a girl. Then they have apparently put me in his arms and I have given him a smile and so managed to win his heart. I did not. Neither the smile, nor anything else I had to offer sufficed for that task. He was quite a handyman. I learned many things watching him mend things. He also had a heavy hand. He could not stand the masturbation of his preschool daughter. He could not tolerate many things. We learned to tread warily around him, lest we should awaken the “demon” in him, as he used to call it. But, well, I always had my “head in the clouds” and “my head always played with my ….” The day I got my period when I was playing soccer with my cousins, he pulled me aside and told me that I had grown up and should be careful about my behaviour. We read poetry together.

I worked on the project for a while. I started to delve into my relationship with Dad. I thought about the similarities between our line of work, our taste, interests, mannerism and moral principles. I had a mind to interview him, but personal issues like my divorce and taking care of him when he fell sick together with my low self-confidence when it came to reaching out to Behzad, who had returned abroad, led to my abandoning the project. After all, I used to think that asking for help from a professor like Behzad on a work that was not a wonder of a work, and thus not worth anything, would be wasting his time. My dad passed away in 2016 when we had fallen out and were not speaking to each other for almost a year.

Naghmeh: His words and actions left nothing in me but anger and shame. Then, one day I killed him during a psychoanalysis session. I picked up a big imaginary mallet and killed him. The shrink told me to look into my dead father’s eyes and tell him what colour they are. I wanted to shout, “Stop this foolish game of individualizing pain. So much for the sociological imagination and all those years of studying! Do you really think that these wounds can be healed with such monkey business?” Regardless, I finally bowed before the high altar of the symbolic and the performative and looked. Through the mediation of the shrink’s words, my father told me to leave behind all of my pain and anger in his moribund body and move on.

In 2019, after forgiving father for all the implicit and explicit violence he had inflicted on me, which quenched my anger to some extent, and after some years of roaming around attending classes, learning, reading and working here or there, I decided to renovate my father’s old office and turn it into my own workshop. It had been shut for about ten or twelve years and was almost in ruins.

The thirty-meter unit on the third floor of an old commercial building from the First Pahlavi era on Manouchehri Street in downtown Tehran was dad’s office for many years before being used to assemble and package his products. The roof was in tatters and you could see the sky from between the remaining wooden posts. It was a huge undertaking, but in spite of the dismal atmosphere of the COVID-19 pandemic, I felt a surge of hope and enthusiasm to restore it from its neglected state.

Stumbling on Daddy’s tools here and there would take me to different memories and encouraged me to keep up with the work. It was as if I was unearthing fragments of myself. For example, there it was: his calliper. I was pretty young when my father showed me how to use it with this exaggerated statement: “You can even measure the diameter of a strand of hair with this!” And from then on, the calliper became a toy and a source of fascination for me. I would eagerly measure anything I could get my hands on, constantly looking for things whose inner diameter and thickness I could measure. I probably developed my almost obsessive preoccupation with precision and size around that time.

Going to the workshop every day and finding the tools and equipment inspired me to start working on the project again. This time, however, I wanted to delve deeper into the relationship I had with my dad and the impact it has had on me. I did not want the work to be limited to its nostalgic or romantic traits. Over the years, many questions had formed in my mind and all of them had something to do with this relationship.

From a young age, I had somehow come to the conclusion that girls are cry-babies and whiners. In order to distance myself from this lameness, I slowly lost interest in the colour pink and floral patterns and everything that was thought to be feminine. It took me years to be able to see them in a new light thanks to artists like P!nk and the shifts in fashion trends and attitudes that changed how men view these colours and designs.

My first friend at preschool was this chubby brunette boy named Hamed. Outside family gatherings, most of my friends and playmates were boys. I loved cycling in the street and playing football. Occasionally, when I had the chance to join in with boys, I felt so proud that I am not like other girls.

Maryam: Even though I never learned how to jump rope, swing a hula hoop, ride a bike or any other typical girls’ games, I always ended up playing the role of the mother in role plays, even when my teammates were much older. And this is the role that I never got to perform in real life.

I revelled in the chance of sitting with men, listening to their discussions about work and politics. I even remember that I tried to imitate them in secret. I would sit on the short stairs of my grandmother’s house with my legs spread, placing my elbows on my knees and resting my hands loosely between my legs.

Fatemeh: I remember that my father did not like my sisters and me to wear revealing clothes in front of him, even when we were very young. He was also very sensitive about how we sat. If he ever caught us sitting with our legs apart, he would say “sit properly!” Even as a child, I could understand why sitting with your legs apart is not appropriate, but to this very day, the reason why certain sitting positions are frowned upon is still a mystery to me. So, I had to be extra careful about the way I sat, making sure that it was always befitting for a girl, without actually knowing what that meant. It was not an easy thing to do. I often felt tense and uneasy around my father. I would try to keep my arms and legs close to my body and even now I feel uncomfortable when I ride my bike, this gnawing thought always at the back of my mind that something is not the way it should be. Living for the first eighteen years of my life in such a household, I have felt restricted and covered up around my dad for quite a long time. I think I have internalized this feeling of unease, limiting my ability to freely express myself.

Apart from how my dad’s career shaped my idea of what I wanted to study, I always thought industrial design meant working in a factory surrounded by a million men. While still a student, I started working for a man and we used to visit different factories together. I would return home excited, sharing my stories of the factories’ facilities and equipment with my dad and he would listen to me with keen interest. One day, armed with my portfolio, I set out down Saveh Road, in the outskirts of Tehran, in search of a job. I visited several factories, but they did not even let me in to talk to them. When Dad found out, he got pretty upset, after all he even did not like it when I used to go alone to the grand Bazar and places like Pamenar and Pol-e-Chubi.

The mandatory internship period I had during the final years of university was very fulfilling for me. I worked in a section of a factory where all the workers, except for the secretary, were men. Every morning that I had to go there, I would wake up excited and all through the day I would walk around feeling so satisfied with myself.

Maryam: Growing up in the middle of a religious and gender revolution in a conservative city and a religious and patriarchal family, I was faced with the reality of inferiority that the women in my society experienced. Especially poignant were the struggles of my mother, aunts, grandmother and neighbours, women sunk under the burden of shattered dreams, having lost the slightest hope in the possibility of pursuing them.

Our house was a place for men to hang out, boys and men who had taken over the house as if the street, the gym and the whole city were not enough for them. Three brothers and their friends, eight male cousins on my father’s side, another four on my mother’s side and a crowd of men whose constant presence only brought suffocating and annoying restrictions for me. Ping-pong, chess, calligraphy, poetry, literature and traditional music were part and parcel of these healthy and intellectual pastimes, activities that forced me to choose between wearing the hijab and locking myself in the room. Sometimes, I received generous invitations from my father and others to “come and play a hand.” But it was with the long skirt or pants and the scarf and keeping a safe distance, things that I could not accept.

I hated them all. My dream was a community of women, dancing and fun, girlishness and polishing our nails, something which was a big no-no back then. Life owed me my femininity, not a generous invitation to a man’s world. I hated all these men because all I could think of by way of solution proved to be in vein. I hated them all, from my father, who was full of love but encaged with thousands of religious and moral considerations, to all the young men of my family and friends, whose existence only hindered my freedom. This aversion went to the point where I began to question if the poems attributed to Saadi and Hafez were actually written by themselves and I was quite sure that they were actually written by women imprisoned and exploited my these me.

I came to peace with men after falling in love at the age of eighteen and going to the single-sex Al-Zahra University. There I got to experience the city of women that I had dreamed of since childhood, exactly at a time when I did not want a unisex community anymore.

The Saxophone Is not a Suitable Instrument for a Woman

I do not remember ever hating my gender. Maybe once or twice when I was a university student and I compared my brother’s freedoms with mine, I got frustrated of being a girl. I enjoyed sewing, knitting, wearing make-up and many other “feminine” things, but the value of “manly” things was much higher in my eyes.

There were not many boys around me in my extended family and those few ones were either younger than me or did not have distinct boylike and masculine characteristics. How had I defined masculinity for myself? Being technical, being rough, fearless, cheeky, being a bully. When Dad came across such boys, he was ecstatic and would start chitter chattering and laughing with them. If I acted that way, his eyes would light up slightly and he would try to contain the faith smile on his lips lest he should encourage me too much. And I would be tickled pink. One of the rare occasions when he supposedly gave me a “compliment” was when my future husband and his family had come to ask for my hand. He said that I am not one of those women who yield to what men want of them. I was giddy with delight and my heart was racing with excitement. Of course one of the reasons that I actually wanted to get married was to become independent and break free of the restrictions that my father had set for traveling or going to parties and which I had yielded to.

I had a brother, but deep down I felt that Dad was not even satisfied with his manhood and that I had to make up for that and make him proud. But my hands were tied. I was a girl after all.

Maryam: My father regrets that none of us have inherited his excellent handwriting and why I do not make any effort to help him achieve his dream, which is to lose at chess to his daughter. Chess was the safest way to raise a modern girl and save face as an intellectual without knowing what I truly desired.

Since I was a child, I was in love with the sound of the saxophone and the poses of saxophone players, just like the pose of Uncle Nader, one of our coolest family friends, in a photo we have of him. I wanted to play the saxophone. Dad never took my interest seriously. There were many other instruments in our house, but I did not have the heart to approach them because my dad and brother were so good at playing them and I thought I could never meet the bar they had set. When I became serious about the saxophone, I found Fouad Hijazi’s number, called him and asked about his classes, but Baba dashed my hopes, saying the saxophone is not a suitable instrument for a woman because it changes the shape of the lips and disfigures the mouth.

Baba was a good driver and he was very particular about other people’s driving and would not trust many drivers to sit in their car. He always praised the good driving of some women, like my aunt, with a twinkle in his eyes. I remember how he would tout the driving of this woman who lived in my grandmother’s street and how skilfully and fast she could steer the car backwards in the narrow alley with those long nails. But there was the rub. I knew that our driver extraordinaire was a Trans woman.

As a teenager, I used to dream that I was driving and I wanted to be one of those good women drivers so bad. I finally became one, but that was not thanks to Dad, who gave the car to me once for every nine times he would give it to my brother. It was one of my boyfriends who put me in the driver’s seat and said, “If you crash, we’ll fix it. No big deal.”

The only time Dad raised a hand on me was when he hit my hand hard with his big, heavy hands for biting my nails. I never forgot that scene, but I continued to bite my nails. He said that a woman’s nails should always be well-groomed and varnished and she should wear red lipstick. His could never hide his look of distain and anger when he saw my bitten nails and “chubby” hands. I was neither a beautiful and perfect woman nor a man.

Fatemeh: My father did not have a son, so he welcomed his daughters to give him a sense of having a son. He used to joyfully buy us bicycles and when he saw a knife or a lighter in the shop, he would offer to buy it for me because he knew I loved such things. The problem was that he wanted us to act like his sons, but at the same time he did not want us to go too far. So I was neither happy being a girl nor could I have the same power and freedom that boys had.

Naghmeh: As I grew older, I learned not to be like my sister so as not to be accused of “the lust for being seen”, “the lust for talking” and the lust for many other things. He was a leftist. We learned to think about others from him, but like many other leftist men, he considered any expression of femininity to be ribald and undeserving. For him, any insistence on your position was a sign of grandiose and obstinacy. When I started hiking, he said: “If something happens to you (read if you get raped or something), you wouldn’t understand. It’s me who has to suffer for a lifetime.” He would get upset when we protested that physical jokes were not an expression of affection.

Maryam: I started my fight from elementary school. I was the only girl in the extended family who got the permission to wear nail polish after so many feuds and arguments and removing the Chador after finishing high school was the ultimate act of breaking taboos in a city where all women wore Chador. At first, I started my struggle with presenting religious arguments and references, as it would disarm the men in the family, men who later all became my supporters and encouraged me to continue my path.

I Feel It Is Time That I Played on My Own Field

Did I really enjoy the things I had chosen to do or was it all more about being different and getting myself a footing in a man’s world, or could both be at play? Did I want to be like men or was my problem with the fact that some roles and activities were seen as only for men? How much of what I had turned out to be was a Nazly with an ever-unquenched thirst for her father’s love and approval and how much a Nazly with her own talents and aspirations who had inherited the foundation of her knowledge and worldview from her dad? Even now, after my father has passed away, why have my choices and sources of enjoyment remained more or less the same? What does it mean to be a woman or a man? What do femininity and masculinity mean? Perhaps because of all the contradictions that I have experienced in my surrounding, themes relating to gender and sexuality, femininity and masculinity had been present in my art practice since the beginning, but with this project I was beginning to view these questions in a new and more in-depth light.

Maryam: And then I was in Tehran, surrounded by a myriad of women from across Iran and we had found each other’s companionship with all our similarities and differences. “I” had turned into “we”. This was a pivotal moment in my life and I was filled with love for my father, something that patriarchy had obscured.

I needed to stay in Tehran and continue my journey. My hometown was the embodiment of all limitations and constraints for me. So, I stayed in the capital against all odds and started working. Marriage followed and several failed attempts at pregnancy and artificial insemination exposed me to a wider range of the feminine experience. My focus on women’s studies deepened over time. I started going to some events at Tehran University Department of Women’s Studies and resumed my studies at the master’s level in order to break free from the grip of depression. I wrote a thesis on the topic of motherhood and attended a course about aesthetics and feminism in which I crossed paths with Nazly.

To seek answers to my questions, I began jotting down memories, sketching mental maps, and archiving anything related to my father’s work and our relationship.

At this point, my workshop had become an ideal venue to showcase my work process and present my project to others. This was a space initially shaped by my father’s personality and its atmosphere and location within urban geography was distinctly masculine. Transforming this space could make it more welcoming to those who shared my views. It could now become a space for the critique of patriarchy and exploration of femininity and sisterhood.

Sonia: I feel like I am missing something that I am more likely to find in this group rather than anywhere else. Until now, all my relationships have been shaped by the male-dominated world—trying to fit in among men, seeking their approval and competing in a field where the harder I tried, the more I ended up shooting myself in the foot.

I am here because I feel it is time that I played on my own field, a place I have not been able to access for years, or if it was within my reach, fear held me back. I was afraid to establish my ground and set my own rules as I thought any power rooted in femininity had a hidden sinister side to it. It felt belittling. It was hard for me to trust myself and other women. It took me years to realise that my attitude towards my gender was driven by fear, violence and contempt, hindering me from embracing femininity without even realising it.

Even now I cannot say that I am here with an unshakable faith, but what I am sure of is that I have to thread this unfamiliar path in order to find that which I know is missing. I have no choice but to scout every corner and put my trust in the possibility of collective discovery.

The first truth I discovered about myself lies in this very concept of “collective.” Women have traditionally gathered around fires, sharing their experiences with each other. The structure of these gatherings is circular or curved, in contrast to the triangular and hierarchical arrangements often favoured by men.

During friendly conversations about my project, I noticed how we women had so much in common in our experiences and concerns and, of course, in the weight of so many unanswered questions that roamed around in our heads.

Mansa: This journey began when I met Nazly, who was passionate about understanding women and exploring “who we are.” And it was not so difficult for us to discover common threads that lie entangled deep within all of us. Sharing became the foundation of our bond. Now, I am pondering: What are the lived experiences of Iranian women? What contributions have we made and on which ground are we standing? How do our society, culture and history perceive and define us? Who are we, really?

Zoya: What does femininity mean? I had never thought about it this way before joining this group. I had regarded what I was as pretty much what the concept meant without questioning it a lot. Now, however, I wonder: Do we have our own definitions or are we simply accepting what patriarchal society tells us? Is there room for choice? These questions have been swirling in my mind ever since.

As women, daughters, wives, colleagues, we have all been harassed and disrespected in society. During these years in psychotherapy, I have tried to forget the memories of abuse from my marital life.

I Had Become One with the Woman inside Me

Initially, I had planned to arrange lectures and workshops around my questions, but as the project evolved I kept encountering new ideas. I try to gain more knowledge, seek advice, listen to other people’s experiences and based on that I choose my path and move forward. Essentially, I am trying to make the road by walking.

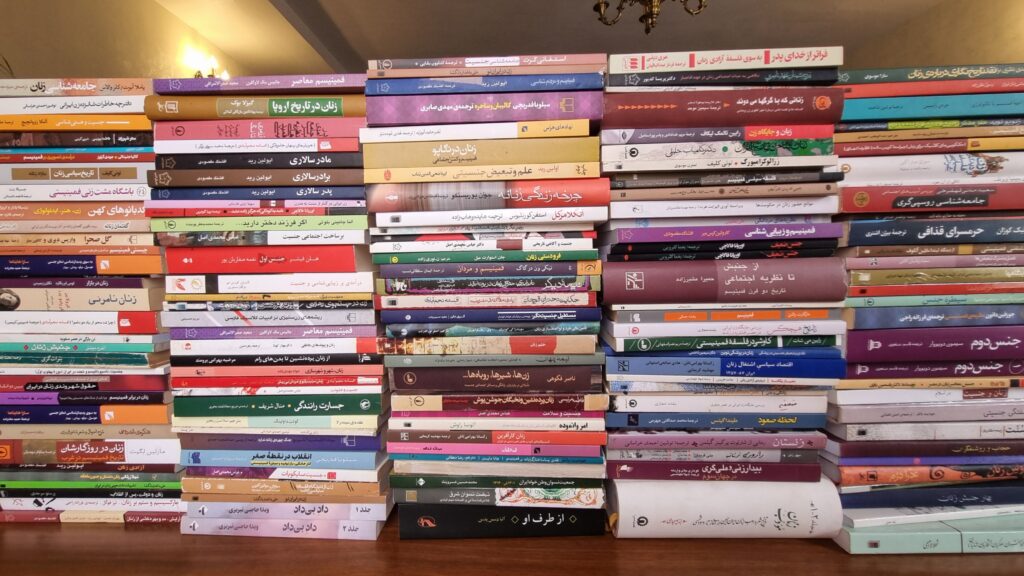

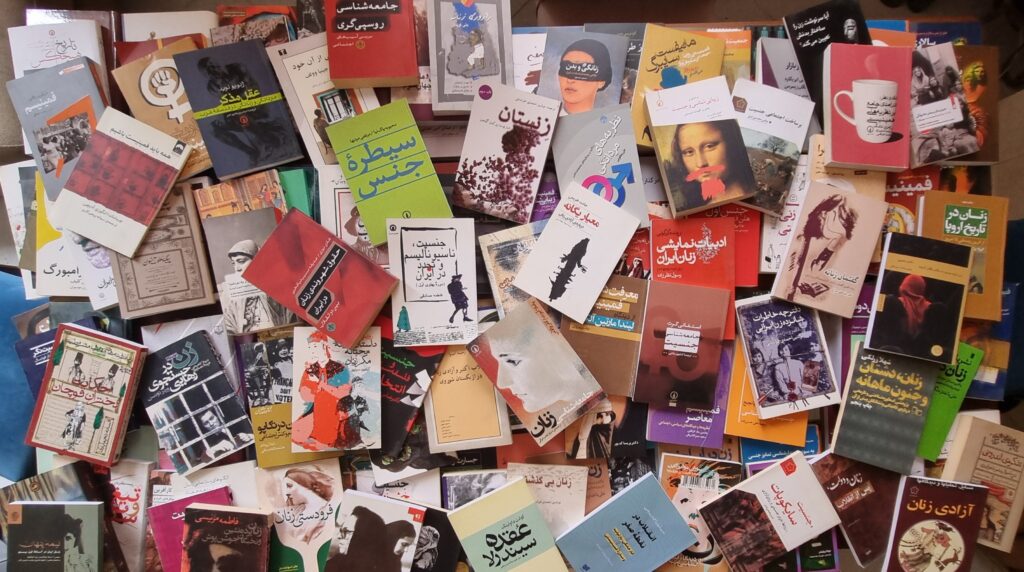

The desire to find possible answers to my questions as well as Behzad’s suggestion to gather an archive of books and resources written in or translated into Farsi on the subject of women inspired me to create a library on feminism and gender studies in the workshop, that traditionally male-dominated space.

I first expected to find about twenty to thirty books, but after looking around I was surprised to realize that there were many more books available. That in itself, however, was a new source of worry as I could not afford to buy all those books. Then it hit me that I could ask friends, family and acquaintances for help. I shared a post on my private Instagram page, asking people to give me a book from a list I made for my 40th birthday. I explained that this would make me happy and support my art project as well. I asked them to write a note inside the book and to consider the library as their own. Besides the birthday aspect, I wanted to involve people around me in the project and it worked. I got gifts of one or more books from a vast group of people I fondly call Jaam-e-Mastan,[i] the congregation of the drunken, and I have been receiving such gifts ever since.[ii] The gifts have given me an excuse to talk about my work with people. People from all walks of life have somehow found a point of connection to my story and project. We share our stories and build a new type of connection which opens the way for collaboration and new friendships.

After reaching out to people for help in building the library, I discovered the concept of gift economy. As I read about it, I realised that it has maternal and feminist origins and that many feminists worldwide have explored the idea. I searched for resources in Farsi or individuals who might have worked on this concept in Iran, but I have yet to find any. So, I decided to delve deeper into the topic. Moreover, as I immersed myself in the project, I found it necessary to explore the workshop’s history, urban setting, and geographical significance. In my reflections and mental maps, I also uncovered traces of the women in my family, particularly those from previous generations. These topics and discoveries will all shape the subsequent phases of the project.

Mansa: I am proud of who we Iranian women are. I believe we have inherited a valuable legacy, marked by significant intellectual accomplishments, which can stand alongside those of women worldwide.

During conversations with others, the need for creating a reading group and getting familiar with what our library’s books had to offer was established. I talked about starting a reading program with one of my friends. After gathering the books, starting this group was another step towards achieving my goal of advancing different aspects of the project collectively. Finally, on March 8, 2021, I once again invited people to join this program through my private Instagram page.

Mansa: I joined the book reading sessions because self-discovery had become a priority for me. There are things which I deeply believe in and things that I have experienced, somewhat more vividly in the past and a bit more subtly in recent times. I wanted these things to resurface so that I can write freely about myself, my thoughts and the ways of being and doing that I have learned from the resilient and wise women in my life. I want to write about these things in a way that would be objective and defendable.

Fatemeh: I have felt like I am invisible for a big portion of my life, that is to say that I felt my presence was not recognised much, most of all in my mother’s family, but also at school and in other groups I became part of. I did have the yearning to be seen from the onset, but no-one really paid any heed to it. This feeling of invisibility probably has many complex reasons which I am not fully aware of, but I do have some speculations about how it came to be. To be seen, you need to express yourself, something that I rarely do in most social settings. There were many things which held me back. One of them is probably related to being a girl.

I was neither too chatty and outgoing nor too quiet and reserved. Even if I sulked or went silent, no-one ever seemed to notice. Of course, I do not want to put all the blame on my patriarchal father as I am sure other factors have also been at play, but I cannot turn a blind eye to these thoughts and guesses either. I no longer wish to be invisible however. I want to allow my desire to be seen to manifest itself. I want to open myself up to others and move my limbs around more freely. I want to dance freely in front of others. Since this is not a wish that can be easily obtained, I welcome anything that can push me forward. Being part of this project is one of them. So, my main motivation is entirely personal.

Anahita: In 2018, after curating an exhibition titled “The City, the Disabled, and Citizen Rights,” we launched a second call titled “The City, Women, and Citizen Rights.” Over 120 artists, mostly women, participated in the call. Surprisingly, more than seventy per cent of the works indicated that the artists had limited knowledge of women’s citizenship rights. This inspired me to, firstly, deepen my knowledge of this field, and secondly, join a group dedicated to exploring and embracing womanhood.

Zoya: Even though Nazly’s project was intriguing for me from the start, I was not particularly interested in feminist studies. I did not believe that raising women’s issues was useful on its own. I used to think that if we promote social justice, everyone would be able to find an appropriate position in society. My primary motivation for joining the project was to spend time with my friends and collaborate with them in possible joint projects. However, our friendship and discussions made me more aware of women’s issues. Now, I think such activities are not only helpful, but actually essential. I am eager to explore various side activities and have exciting experiences with my friends.

Maryam: Numerous surgeries and use of anaesthetics has had detrimental effects on my memory. Quitting my job and staying home for years had once again turned me into an isolated woman, lonely and anxious. It was time for “I” become “we.”

Nazly’s idea of forming a reading group ignited a spark of hope for me to overcome my many challenges. One of the worst things was having forgotten the content of many books that I had read about women’s issues.

I have had experience in bringing arguments and references to support my cause. Now I had to overcome depression, loss and isolation. I think I was one of the first people who responded to Nazly’s invitation.

We chose an easy reading book to start with and began online meetings with a small group of five or six people. At the end of each book, we collectively decided about the next one and new members joined us at the beginning of each new book. The mandatory online method of holding the sessions due to the COVID-19 pandemic allowed people from different cities and countries to participate and the meetings were held once every two weeks.

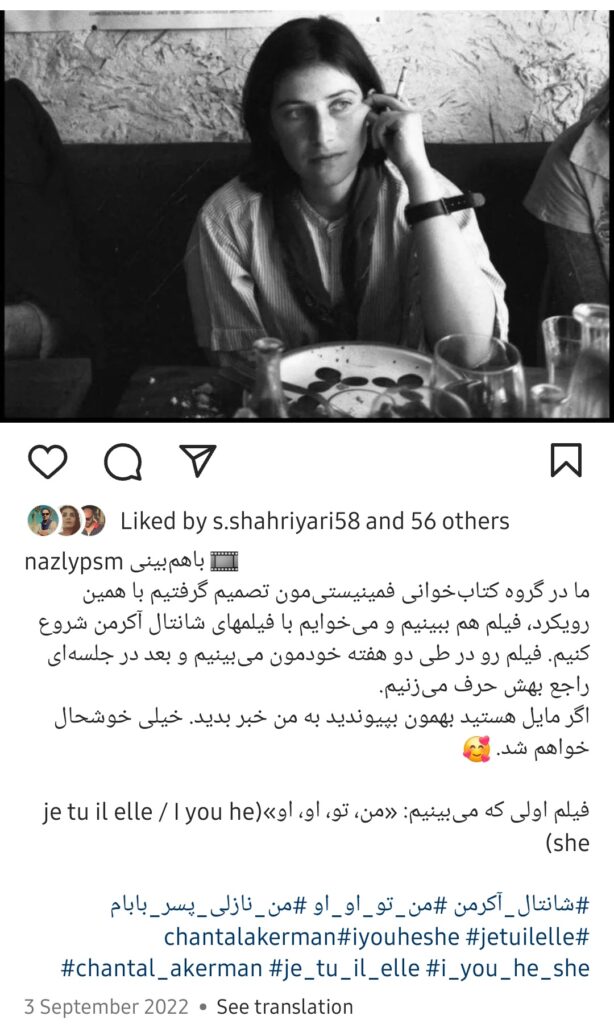

Since we were all women and the level of our familiarity with feminist knowledge and literature did not differ greatly, our discussions often ended in sharing our personal experiences and narratives. These meetings and our shared concerns gradually created solid and sincere relationships among us. We talked about ourselves, heard new perspectives and thought deeply about them. We learned from the books as well as from each other and we embarked on a path of growth that we have been following to this day. We raised various issues and thought about practical activities we could do together. Despite differences in age and viewpoints, the collaborative process of our meetings made it possible for people to remain connected with the group and other members even when they were unable to participate in the discussions at times. For a while, a group of us gathered for a series of sessions to watch movies with the same approach. Apart from reading books and watching movies, we think together about possible collective projects and help each other when needed. We have gone far beyond a mere reading group.

In order to write a polyphonic text together as a group, I asked everyone to write a few lines about their reasons for joining the group and describe their experience during this period. Some of the members, and not everyone, wrote from a paragraph to a page. I also started writing about the project myself with the help of two of the members. When we read our texts upon submission, we were surprised by how similar our experiences were to each other. It was as if we had read each other’s hearts and minds and had written our pieces to continue or elaborate on someone else’s text. We came up with the idea of breaking the writings into pieces and putting them together like a puzzle in order to create one single text. The text you are reading is the result of this very process. Whether it is me who is narrating or someone else’s name appears at the beginning of a paragraph is not important. The narratives ultimately complement each other to form a unified story.

Mansa: I feel like there is something in my throat, a lump that cannot be put to words and its merit is exactly just that. But I feel the onus is on me to try to write about it in honour of all the women in my life—those I have met as well as those whom I never got to know.

That is why I am in this group. I am here for the sake of that which I see in the eyes of every woman here and which amazes me; for the sake of that which we are unable to express fully in spite of all the conversations we have. These unspoken words have resided in our hearts for so many years, passed down from generation to generation, those untold stories which define us as Iranian women, embodying a femininity that reveals its beauty in each of us.

I am here with a passion to observe and learn from the woman who resides inside each of us, the one who is always there, comforting and reassuring us, saying softly, “It’s going to be okay.”

Sonia: Here, I find pieces of myself in others, others who, like me, have not been narrated, heard or recognised for years. We have all denied and repressed parts of ourselves for so long and now, none of us can deny its existence any longer. We are all confronted with a pressing necessity: to response to a woman who asks: “Who am I?”

Sareh: For me, femininity conjures up the feeling of being voiceless, like when you are under the water, squirming frantically and trying to shout your words as loudly as you can. Still, in the end, only thousands of bubbles rise to the surface, there is a minor turbulence and then silence is resumed.

I end up breathless. I am stuck in a never-ending cycle of marital life taking me to a terrifying no-man’s-land, pulling me under again and again.

I used to throw big parties, overladen with the weight of definitions of being a woman. I attended customary gatherings, cleaned my house, did my makeup, chiselled my body and raised my daughter and all the while the word “separation” had loomed over my life in the many shapes of threats, fear, fighting, silence treatments, depression, distance and disintegration from the very first day of a sixteen-year marriage.

Desperation seems to be the right word. Those days, I used to put myself through the mill, trying to follow the path of the bubbles and reach the surface. My silent shouts had turned into a current, and unknowingly, I had broken free from the murky depth of the water. I had reached the surface, but I did not know what it was.

One day, standing in front of the mirror, I saw a woman with wet eyes who had embraced me all through those difficult years, followed the story of my life with anguish and listened to me compassionately. A woman was looking at me from within. She was so warm, so comforting and omnipresent that I did not feel alone anymore. The woman inside me was secretly fine. She was always good enough. She did not have to pretend.

When I was on my period, the woman inside me called the world to war with a thousand shades of the colour red. She would drop the shackles of composure, spit out all the frameworks of femininity, wrap them in a newspaper and send them to hell in the blackest of envelopes. Those days the woman inside me was a woman and she was not. She was impure. She did could not say her prays. She did not get laid. She did not get pregnant.

One day, I came to and realized that I had shed my skin or perhaps burst the cocoon. I had become one with the woman inside me and we walked out of wedlock hand in hand. We were still in the middle of nowhere, but this time she was burning the bridges behind us and I was singing.

Except for a few times, like during war time when Dad produced anti-tank mine frames, he never accepted orders or made products for others. He also did his own marketing and distribution. At the turn of the century, when small scale production had become difficult due to the flood of imported Chinese goods, he offered my brother to join in and take over the business. He probably did not want all that creativity, effort and hope to go down the drain. But unlike me, my brother did not like technical work and the atmosphere and logic of such businesses. He worked with Dad for a while and then quitted out of boredom and his disagreements with Dad. The business was shut down shortly after that and my brother moved abroad.

Among the things I found during the renovation of the workshop were a couple of moulds that I sold as scrap metal to cover the expenses. There were also some wheeled plant pot saucers that I thought I could sell later if I was ever tight with money. A while ago, a friend who had seen the saucers and wanted to buy a couple asked me, “Is there any part of your dad’s business that you can continue? Something like these vases?” The question hit me like a thunderbolt. Now, after all these years, I find myself sitting with this thought that burns me to the core: why did he not offer me to continue his work? And of course it is interesting is that the thought had not even crossed my mind at the time, maybe because the answer was too obvious.

Fatemeh: Even the title of Nazly’s project, “I, Nazly, My Father’s Son”, can explain a large part of my life. I joined this project to share my story and listen to others. I want to experience sisterhood, womanhood and everything related to my gender as something valuable not something disgusting and insignificant. My second motivation is more of a collective nature. I want to be part of a community whose members try to make peace with themselves as much as possible.

Naghmeh: These past few days that I was trying to write these thoughts in my head, I kept being reminded of Romina[iii]. I killed my father in my mind in the psychoanalysis room. Her father killed her in bed. Sometimes, I think the only thing that has made our fates different is our class. Our pain is not individual. We need to find each other. We need to talk about these things that make us similar and separate us.

Maryam: Now, I hope that after the COVID-19 pandemic, we can rebuild a more robust collective “we” so that the weakened I can stand tall once more.

Baba, I wonder how it is that I seem to be following your footsteps. After your office and workshop, now the house and bedroom you spent your last years in have become mine, a place you were forced to go to, but I am moving in by choice. You used to call it “the end of the world.” What was your definition of the end of the world, by the way? Now, I will forge a new beginning from the end of your world. We will forge a new beginning. This is perhaps the biggest difference between you and me. You believed in “I” and I put my hope in “we.” Maybe we can get to more beautiful places.

[i] Term borrowed from the poetry of Hafiz, the fourteenth century famous Persian poet.

[ii] Some of the gifts have been in form of monetary donations. Some lecturers whose courses I have attended on the topic have waivered their tuition and a friend donated her alimony money after getting a divorce.

[iii] Romina Ashrafi was a fourteen-year-old girl who was decapitated by his father with a sickle to clear his honor after she had eloped with an older man from a neighboring village.