Once upon a time…

The point of departure for this article is the monument at the center Felestin Square of Tehran and its historical background. Palestine Monument was erected in 1989-90 as the first public monument after the 1978 revolution in Iran. Here, my analysis goes beyond the physical location to address the phantasm, imagination and spatiality that surround this monument, viewed through the lens of contemporary history of art and politics. In fact, the monument in Tehran is a site- and context-specific example that serves as a conceptual point of departure for investigating an array of analogous political contexts and historical entanglements. By elaborating on the relationship between two hyper-politicized social environments—Palestine and Iran—I attempt to bring micro levels of historical narration into dialogue with the multiplicity of the relations between art and politics.

I approach these issues from different historical perspectives, investigating the materiality of contemporary history and the multiplicity of interactions, connections, entanglements, and micro-histories embedded in our near past. Through the reenactment of material history, I ask how art and the praxis of artistic research can excavate the image of contemporary history in the present and suggest a possible future for it, as well as, what has happened to these images after they crossed the border?

At the intersection of Felestin (Palestine) and Talaghani Streets, in the middle of a large roundabout, there is an allegorical bronze-and-cement sculpture. Depicting several figures, one with a fist raised in a gesture of defiance, the work is a monument to the Palestinian struggle and, in particular, the First Intifada which lasted from December 1987 until the Madrid Conference in 1991. It was precisely during this period when the construction of the monument took place, from 1989 until its inauguration in 1990. The sculpture was the first public monument ever built in post-revolutionary Tehran.

Under the Dermis of History

“Why is the map upside down?” my Palestinian friend instantly asked when I showed him an image of the monument from the Google search results. I had not noticed the map was upside down. It was an agonizing moment and I did not have an answer. I Googled “Palestine map.” The first image that appeared bore the title “The Palestinian Historical Compromise,”and was comprised of four maps: Historic Palestine, 100 percent; 1947, 44 percent; 1967, 22 percent; and the present1, 16 percent.

I Immediately felt the need to explore more, to embark on an archeological attempt to shed light on what I had taken for granted about Palestine. I had to dig into the “dermis” of history and attempt a sondage of the stories buried beneath this upturned allegory—a deeper investigation into a part of a broad trench of history.

How could I talk about these stories? Was there a story camouflaged within the colonial past and present, one that had resisted and endured? I had to ask myself: “How can I understand the monument in relation to the history of Palestine?” Such an endeavor could be a form of activism, but at the same time it took place under the shadow of a discourse supported, founded and built by another hegemonic order which itself occupies Palestinian resistance to achieve its own political gain with regard to the Iran-Israel relations. How do the notions of activism and art play a role here in the center of Tehran? And what will happen to the narration when it crosses the border?

There are resemblances between the Palestinian condition and the one I call hyper-politics. I define hyper-politics as a permanent state of life within an organic crisis, a realm where any action or motion is immediately associated with one or the other side of a conflict that has taken place in the abyss of past millennia, or else will occur in the future (whether today, tomorrow, or decades from now). That is to say, both Palestine and the hyper-political reflect colonization by the grand narrative of history. Nevertheless, there are even more discontinuities and dissimilarities. Layers of histories, from the colonial period of the Mandate for Palestine2 to the post-1947 occupation, make the Palestinian issue an eternal battle between the colonizers and colonized, the oppressors and oppressed. The colonial conquest has proceeded, millimeter by millimeter, to subjugate the immense expanse of land that lies between two rivers3, the promised land that I cannot go to. And indeed this constitutes the main obstacle in the way of my thought process. Where does memory begin? Perhaps it emerges not as a tool to access the past, but from the earth in which the past lies buried.

A Letter from an Exiled Kid from Palestine

In the mid 1980s, I was eight years old. One of my second-grade assignments was to write a letter to a Palestinian kid. The imaginary Palestinian kid in our school textbook had already sent us a fictional letter, in which he had told us his story and talked about the situation in Palestine—the suffering, pain, death, murder and the inhumanity of their living condition.

He had said: “Do you know me? I am your brother. I am Palestinian. We Palestinian kids are Muslim. The name of our country is Palestine. You, in your own country, live in your home, but we live homeless in the deserts in exile, because the enemy has occupied our home and our country. We spend day and night in the tents and we study in the same tents. The enemy kills us and burns our tents. I must say that since your revolution began, the enemy is more fearful and because of that they torture us more.”

To practice writing a letter, we had to send our replies. It was perhaps the first letter that I ever wrote. I do not remember the content. I, probably, repeated whatever our teacher had told us to write. In the process, we learned new words and phrases, such as:

Occupy (اشغال): to take by force

Return (بازگشت): to go back

Adrift (آواره): to be without a home, to be forced out of one’s country

Exile (تبعید): to displace, to banish

Protest (اعتراض): to disagree, to oppose something

Tabernacle (چادر): tent

Executioner (شکنجه گر): killer, murderer, torturer

Break the silence (شکستن سکوت): to begin to talk

And there were other new terms, such as struggle, combat, and explosion. That page of our school book was illustrated with a portrait of a Palestinian kid, gazing out with his big eyes—very large eyes, I must say—wearing the Palestinian keffiyeh. In the background, there were a couple of tents in a phantasmal desert. The illustration shaped the basis for my impression of Palestine for a long time. Representations of distance and barriers seem to have played a defining role in our understanding of Palestine and Palestinians in Iran. Indeed, in 1980s they served as a vehicle for the production of a collective imaginary of Palestine and the Palestinians; they formed and perpetuated a certain notion of occupier and resister, and the associated war with anger, and emancipation with occupation.

When did the imagery of exodus and resistance become representative of Palestine in Iran? And what happened to these images after they crossed the border? Adoption of a stance on the pain of others eventually became part of Iran’s political agenda and was used to clarify its foreign political doctrine and, perhaps even more importantly, served as a domestic tool to differentiate between friend and foe. Palestine was a token and a useful other in pain which could justify the Islamic republic’s claim of being a supporter of proletarians of the world.

An Unknown Plane

Early in the morning of Monday, February 18, 1979—a week after the Iranian military’s declaration of neutrality and the announcement of the victory of the Iranian revolution—the control tower staff at Mehrabad International Airport received a landing request from an unknown foreign plane. Due to the environment of political uncertainty, Iran’s airports had become accustomed to such irregularities over the preceding two months.

The plane carried the leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization4, Yasser Arafat, along with fifty-eight other PLO officials. The irony of Arafat’s visit was evident: Arafat was treated as a hero in the same land that had supplied much of Israel’s oil, the country where Israelis had participated in training the SAVAK, the Shah’s secret police, and where both Israeli and Iranian pilots had trained on US-supplied F-4 Phantom fighters.5 Iranian opposition to the Shah and the Palestinians shared common historical ground. Some of the Iranian revolutionaries had trained in PLO camps in southern Lebanon, where they had merged with the Lebanese Shia villagers and their militias.6

During his visit, Arafat proclaimed that Ayatollah Khomeini had assured him that Iran’s revolution would remain unfinished until Palestinians achieve their goal. The PLO had established a mission in the former Israeli embassy in Tehran, as well as in Ahwaz and Khorramshahr, in the center of the Iranian oil province. The PLO representative in Tehran became Hani al-Hassan of Fatah, its conservative Muslim wing. By selecting a more Muslim-oriented representative, Arafat sought to send a clear message of adherence to Khomeini’s ideas about the Islamic identity of the Palestinian resistance. At an official ceremony attended by both the prime minister of the interim government of Iran, Mehdi Bazargan, and the short-term foreign minister, Karim Sanjabi, the keys to the Israeli embassy were ceded to the PLO leader. It was then that Felestin Street, on which the embassy is located, along with the nearby Square, received their names.

Some members of Arafat’s entourage eventually stayed in Iran, managing the PLO offices in several cities.7 The divergence between the PLO and the Iranians began immediately after Arafat’s arrival and his two-hour meeting with Khomeini. Khomeini leveled deep-seated criticisms of Arafat and the PLO. The Palestinians were shocked to encounter the angry imam instead of a welcoming spiritual leader. Khomeini lectured Arafat on his obligation to get to the Islamic roots of the Palestinian issue, and warned against his leftist and nationalist tendencies.8 In addition, the Iranian leader suggested an Islamic orientation to the resistance would increase Palestinians’ chances of victory, as well as preclude a takeover by Marxist and communist tendencies among their ranks.

Even though leftist-oriented ideologies, mainly Marxist-Leninist, had played a significant role before and during the revolution in Iran, the anti-left rhetoric would eventually prove influential in post-revolutionary Iran. Nonetheless, when it came to Palestine, such political rhetoric constituted an Iranian attempt to overtake the Palestinian movement. Ultimately, however, Iran’s efforts to influence the direction of the Palestinian resistance, whether on the basis of Arab nationalist identity or its opposition to socialism, would not play a major role.

This identity crisis unfolding between the Iranians and Palestinians was not just at the meta-level of political ideology: as one of the Iranian hosts complained, none of the Palestinians were religious. Most of them drank alcohol and they wanted to watch films.9 “Were these really Palestinian?” the Iranian revolutionaries asked themselves. The imaginary Palestine that Iranians had created in their minds did not resemble the reality. Such ideological dissimilarities between the Iranian revolutionaries and the PLO representatives led to an atmosphere of ambiguity that would prove damaging for future attempts at collaboration. Soon after the revolution, when tensions emerged between Tehran and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states, Iran began to publicly accuse the PLO of exacerbating the impasse between the Arabs and Persians in Ahvaz, a city largely populated by Arabic speakers.10 Only a few months after the inauguration of the PLO’s Ahvaz office, it was shut down and the PLO embassy in Tehran was placed under close surveillance.

In order to compensate for its actions against the Palestinians and appeal to the broader Arab and Muslim masses, the Islamic Republic turned to rhetorical means to cover up its actual policies. It was then that Khomeini declared the last Friday of the month of Ramadan each year to be Quds Day, exhorting Muslims worldwide to demonstrate on that day in support of Palestinians.11 However, Quds Day celebrations merely demonstrated that Iran’s disinclination to deliver concrete support to Palestinians had become more sedimented as an ideological position.12 Khomeini’s strategy might have as well been an aesthetic one.

Then, the war between Iran and Iraq broke out. Arafat sided with Saddam. The hero became a tabloid caricature. Hyperbolic depictions of Arafat’s secular, Marxist, Arab-nationalist identity became a permanent feature of Iranian revolutionary narrative.

The Nakba

On April 2nd 1947, the British government submitted a request to the United Nations for the formation of the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). Britain faced significant challenges toward the end of its mandate over Palestine, including the Great Palestinian Strike and Uprising (1936–1937) and the Zionist Jewish riots (1944–1948), compounded by economic difficulties following World War II. As a resolution to these issues, Britain handed over the Palestine question to the newly established United Nations, effectively transforming it from an internal colonial matter into a global concern.

Trygve Lie, then Secretary-General of the United Nations, invited the members of the General Assembly to the first Special session from April 28th to May 15th. The session aimed to address the formation and mandate of a special committee for “Constituting and instructing a special committee to prepare for the consideration of the question of Palestine at the second regular session.”13 After extensive debate about the composition of the committee, members of the Security Council, the Great Powers, and all Arab nations in the region were excluded to avoid potential conflict of interest. Instead, it was decided that the committee would be comprised of representatives from neutral countries.

At Australia’s suggestion, the Committee’s membership was set at eleven countries. After the composition and terms of reference were approved by the special session of the General Assembly, the Committee began its work on May 26, 1947. The eleven member states—Australia, Peru, Guatemala, Uruguay, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Canada, India, Yugoslavia, Sweden, and Iran—each sent one representative and one alternate to the Committee. Notably, all members of the Committee were men.

The Special Review Committee presented its two proposals to the General Assembly on August 31, 1947, nearly a month before the deadline. These were the minority and majority solutions. The majority solution, proposed by Uruguay, Peru, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Canada, Guatemala, and the Netherlands, recommended partitioning Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem designated as an international zone.14 In contrast, the minority solution advocated for the establishment of a single federal state.

Critics of the majority plan argued that it disproportionately favoured Zionist interests. Despite the Arab population being twice as large as the Jewish population, 62% of the land was allocated to the Jewish state. The partition plan was welcomed by the Jewish Agency and most Zionist organisations, who viewed it as a cornerstone for territorial expansion. Conversely, the Arab League rejected the majority plan and opposed the partition of Palestine.

Iran, India, and Yugoslavia opposed the partition plan, instead supporting the minority proposal for a federal state with Jerusalem as its capital. Ultimately, the General Assembly voted in favour of the majority plan, and Resolution 181 was adopted. Iran’s representative to the United Nations and a member of the Palestine Review Committee, Nasrallah Entezam, voiced strong objections. In his December 1947 speech to the General Assembly, he warned: “The partition plan for Palestine will turn the Middle East into a permanent battlefield.” Iran and twelve other countries voted against Resolution 181.

Following the declaration of the state of Israel in May 1948, Zionist militias—soon to become the Israeli army—initiated the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, displacing over 700,000 individuals. Palestinians refer to these events as the Nakba, or catastrophe.

The Man Who Drawn the Map

Paul Moan was a Swedish alternate member of the Review Committee, but he became one of the most influential figures in the process. He was the one who drew the partition plan. He wrote in his memoirs: “I realised that the report of the Review Committee had to include a preliminary sketch. I was there until the last minute to sort out the situation. I was left alone in a dark room to sift through the fragmentary maps of the proposed partition plan for Palestine.” On the day of the vote, November 29, Emil sandström, the Swedish representative on the Review Committee and leader of the majority group, invited the countries of the Review Committee to sign Moan’s plan. Moan wrote in another part of his memoirs: “I tried to compare the ideas of partition with each other, hoping for cooperation between Arabs and Jews and fearing hostility between them. … Whether my proposal leads to peace and cooperation or war and hostility is a question with both outcomes theoretically possible.”15

A Postmodern Bricolage

Before the 1979 revolution, the square’s center had been occupied by a fountain, surrounded by statues of Putto and swans. Today, its focal point is the Palestine monument with its central feature being the upside down map.

During the 1990s, the square became a location for anti-Israeli demonstrations which took place annually on the last Friday of Ramadan (known as Quds Day). This location, however, is not defined solely by its political connotations: up until a few years ago, there used to be an art school near the intersection between Felestin and Enghelab (revolution) Streets, and the several small optometrist shops that flank the street also point to the square’s everyday identity.

On one side of the bronze-and-cement monument, a mother protects her child, in a reinterpretation of the Pietà by Michelangelo. On the other, there are two masked men. One man marches with his right fist in the air and a book in his left hand; the second impersonates an Intifada stone thrower. In the middle of the map, there is a hollowed-out silhouette of the Dome of the Rock. Social realism and neoclassicism fuse in this bricolage. How did this amalgamation of themes take shape in this sculpture?

The Trembling Hand of Social Realism

On November 6, 1979, just two days after the occupation of the US embassy in Tehran, Amiradham Zargham, an art student from the University of Tehran and a Muslim revolutionary, approached his Assyrian Christian Marxist teacher, Hannibal Alkhas, to propose an idea for a mural on the wall of the newly occupied US embassy. As Alkhas, who was affiliated with the Tudeh Party16, later described,17 their conversation centered on the essence of art—the notion that painting is a form of labor and a reflection upon events which can serve as a means to communicate with people. He expressed a strong desire: “if only they would let the students paint a mural on the wall of the embassy!”18

Alkhas took the proposal seriously and sent a letter to the embassy’s administrators. Just four days later, they received permission to narrate the event of the revolution on the wall of the embassy on Talaghani Street. The fifty-square-meter wall, thus, became the first revolutionary street art in Tehran.

Immediately after the first wall painting, Alkhas’s students began to scour the city for more walls they might adorn according to their revolutionary desire. Nilofaur Ghaderi Nejad, one of the young and ambitious students, described the environment with these words: “We learned and talked a lot about social realism, Mexican revolutionary painters such as Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco in Alkhas’s Atelier. We were very excited and looked for an opportunity to do similar things on the walls of Tehran.”19 Tehran had become an open canvas for Marxist art students to practice and explore what they had learned from their teacher.

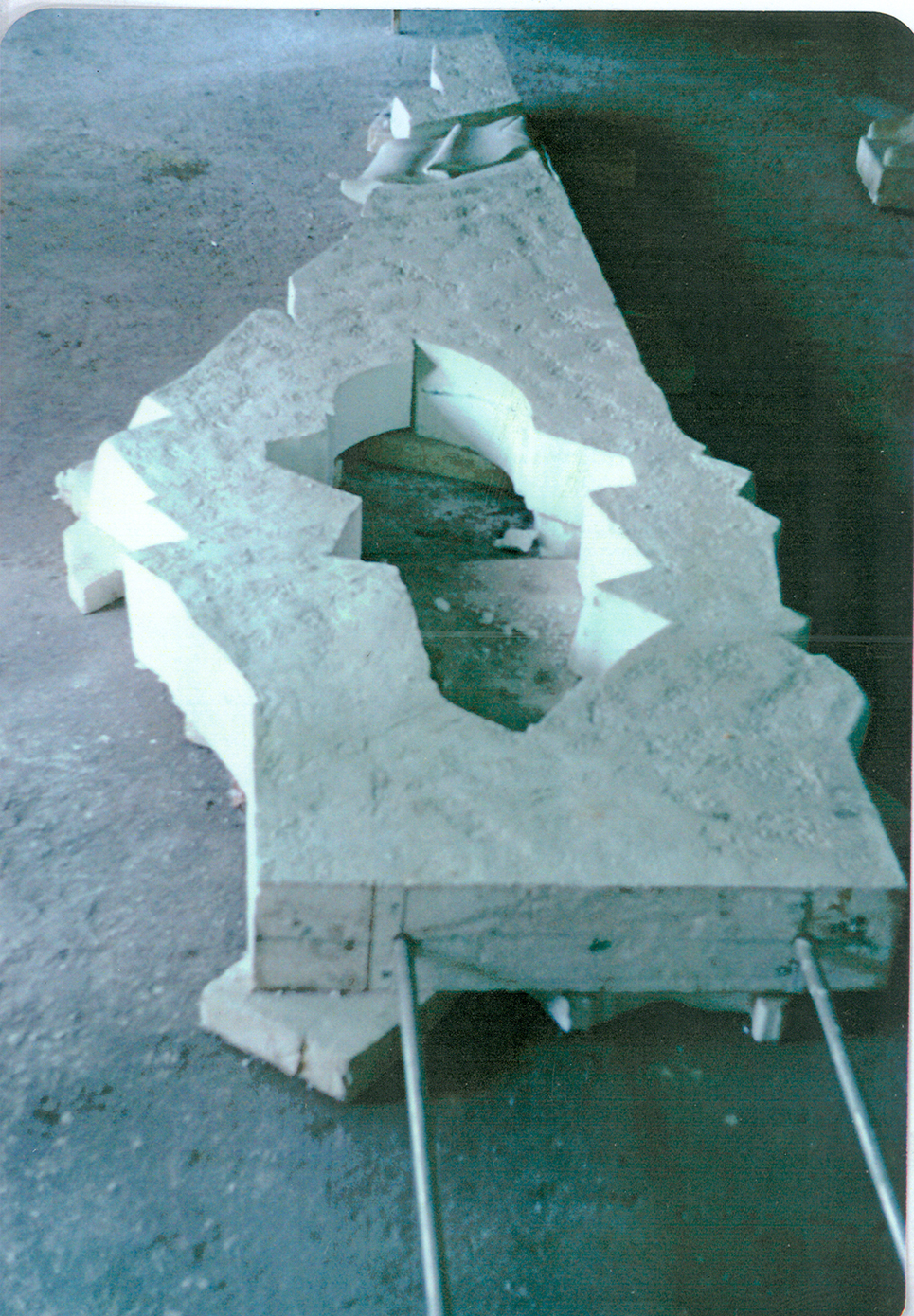

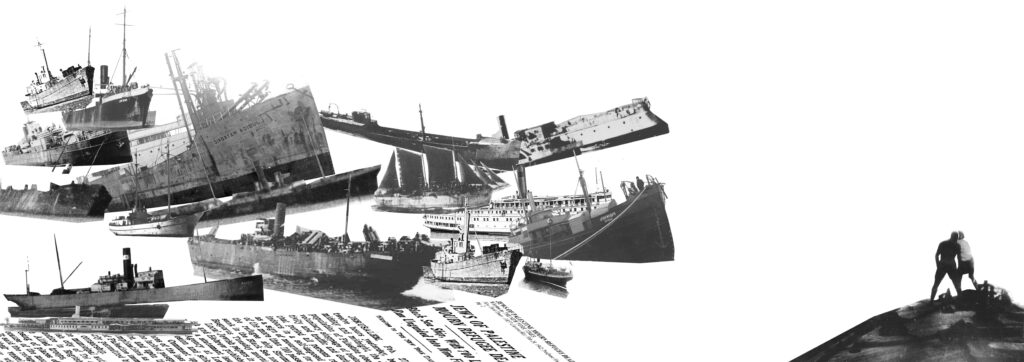

The Collages spread in between the paragraphs of this text refer to the historical events which are recounted here, snapshots of history which narrate the relationship between Iran and Palestine and the creation of the monument. These collages are not only a mere visual accompaniment to the text. They are, in fact, concrete designs proposed to be displayed for public view on the wall of the Palestinian embassy, from the square to the embassy’s entrance. These murals provide a space for narrating the history of Palestine from 1948 until now. They are collages for the future. The picture above presents proposed design for the future of the Felestine square in Tehran. The statue in the shape of the map of Palestine will be place in the correct direction and will occupy a place above other elements in the roundabout. By repositioning the statue in accordance to the actual shape of the map, it will better resemble the shape which has become a symbol of emancipation for the people of Palestinian.

When Socialism Comes from the West

Alkhas left Iran for the United States in the mid-1950s, hoping to be a medical doctor. However, he immediately changed his mind, deciding on philosophy, and then, not long after, settling on art and painting. He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago under the supervision of Boris Anisfeld, a Jewish Russian-American symbolist painter and theater designer and a close friend of Maxim Gorky.20 Perhaps the development of Alkhas and Anisfeld’s close relationship was due to their shared views on the multiplicity and complexity of their social position, something that each expressed through the eclectic use of religious motifs and symbolism. In Anisfeld’s work, this tendency was surely a reflection of his need to assume several identities at once, including being Russian, Jewish, and an artist. For his part, Alkhas’s work reflected his positionality as an Assyrian, a Christian, an Iranian, and later a Marxist artist.

It was around this time that Alkhas became increasingly mesmerized by Marc Chaghall’s painting, Mexican revolutionary muralists, as well as the prehistoric Assyrian motifs from ancient Mesopotamia. After his return to Iran in 1963 and joining the Tudeh Party, he sought to introduce muralism to urban postrevolutionary Tehran. As he believed that galleries were ill-suited for proletarian art, he deemed it essential to bring art to the public in the streets.21

Alkhas soon became an influential professor at the University of Tehran, particularly among revolutionary students, whose views represented a wide range from Marxist to Islamic ideologies. Although his Muslim students engaged with his socialist approach toward art and painting, they eventually tried to claim an autonomous position as Muslim revolutionary artists. The distinction was apparent by the time his students painted the mural on the wall of the US embassy, after which Alkhas was accused by other Iranian political oppositions of supporting Islamists. He elucidated his political position by pointing out the specific features he painted: “I simply painted the first stage of the revolution, which was about proletarians and farmers, independence and anti-imperialism. Zargham painted Khomeini.” He continued, “I won’t be ashamed of my actions in the future.”22

Alkhas’s activities as a teacher and artist played a significant role in the introduction of socialist art to the art scene in Tehran. He suffered from essential tremor, a condition which meant he could not hold the brush properly in his trembling hands and which affected the realism of his work. Were all the exaggerated features_ the free-form lines, the deformed bodies_ in his work in fact the result of his tremor? Could he have become a renowned social realist painter if he had not developed this condition? In any case, the fact remains that socialist painting was introduced to Iran by an artist with an unsteady hand.23

The struggle between Islamist and Marxist ideologies soon led to the onset of the Cultural Revolution. Attacks began against foreign forces on university campuses. On April 18, 1980, following Friday prayers, Khomeini gave a speech harshly condemning the universities. “We are not afraid of economic sanctions or military intervention,” he declared. “What we are afraid of is Western universities and the training of our youth in the interests of West or East.”

During the Cultural Revolution, the universities were shut down and would not reopen for three years. Leftist ideology was once again stigmatized and frequently viewed as a vestige of the political situation before the revolution. Before long came the arrests of members of leftist political parties, including Ehsan Tabari—the head of the Tudeh Party who had been involved in the establishment of the first government after the revolution—and Saeid Soltanpour, the director of the Iranian Writers’ Association. Tabari took part in forced confessional interviews on the national television after being tortured and Soltanpour, who was arrested on his wedding night, was executed two month later in the infamous Evin prison.

The first revolutionary mural on the wall of the US embassy—a visual collaboration between a Marxist and an Islamist—was soon concealed by a coat of white paint.

In his book, Art of Revolution, Morteza Goudarzi Dibaj argues that the reason the practice of sculpture was absent in the first decade after the revolution had to do with the economics of producing sculpture, as compared to painting. An additional, and possibly more crucial, reason was the uncertainty about the official Islamist stance on statues and the ambiguity of the supreme leader’s position on the medium. However, when the University of Tehran reopened after the Cultural Revolution, it actively anticipated the emergence of the medium with the creation of a new department of sculpture.

أن تكون ملكيا أكثر من الملك (More of a royalist than the king)

On Wednesday, March 31st 1990, the nine-meter Palestine monument was unveiled in a ceremony organized by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard and the municipal government.

Ata’ollah Mohajerani, a senior member of President Hashemi Rafsanjani’s cabinet, gave an opening speech in the presence of an ambassador from the Palestinian embassy, a representative of Hezbollah from Lebanon, and representatives of the Palestinian movements Fatah and Hamas. He detailed the two years of planning and competition that had resulted in the bronze-and-cement sculpture. Mohajerani emphasized that the monument is a representation of the close relationship between Iran’s Islamic revolution and the revolution of the people of Palestine—which, in fact, was both a continuation of and strongly influenced by the Iranian revolution. To back up his argument with regards to the international impact of the Islamic revolution, he cited former Fatah activist Mounir Chafiq, as well as the Irish political scientist, Fred Halliday.24 He concluded his speech by proposing the idea for a new monument—one that would emphasize the Islamic foundations for solidarity between Iran and Palestine—which would be placed in front of the presidential building at the south end of Felestin Street. This idea would never come to be realized.

At the end of the ceremony, two of the guest speakers, a representative of the Palestinian embassy in Tehran named Mohammad Mostafa Jahir and PLO ambassador, Salah Zawvavi, expressed the hope that in the very near future all Muslims in the world could pray together at al-Aqsa Mosque. The PLO delegates were actively engaged and involved in the design of the monument by suggesting an additional element, a Palestinian mother.

A Fat Lazy Cat

In the summer of 2014, I published what might be my most bitter essay. The one-page text was published in Tandis, a biweekly art magazine in Tehran, as a complimentary part to a visual report on the opening of an exhibition about Gaza and the occupation of Palestine sponsored by the Ministry of Culture and curated according to official rules of Islamic guidance. The exhibition took place in the midst of Israel’s renewed siege of Gaza and the West Bank. Devastating news and horrific images repeatedly detailed the timeline of the Israeli military operation and the mercilessness of its incursion into the occupied territories.

Such bombastic political rhetoric against Israel became even more visible in Iran during the siege of Gaza. During that time, a group of contemporary artists decided to have an exhibition about Palestine. The exhibition included visualizations of violence, romantic observations on the devastated landscape, and poetic criticism, accompanied by soft background music and the scent of perfume and cologne. The state of affairs with these questionable features was exasperated by the social and political implications of the bourgeois venue. The exhibition was held at the Niavaran Historical and Cultural Complex, located in northern Tehran, near the palace of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. The complex is known for its distinctive architecture, designed by Queen Farah Diba’s cousin, Kamran Diba.

It was perhaps the combination of these elements that so aggravated me, the audacity to define this as “politically engaged art” while surfing upon a river of blood. The artists’ engagement with their practice was like that of a fat, lazy cat living in a bourgeois house: they were simply waiting for an opportunity to catch your eye and get petted. It seemed that the bloodbath in Palestine was an opportunity for them to pantomime political engagement—or even activism—from a privileged place of safety and comfort. And even more importantly, their artworks realigned them with the official stances of the Iranian government and Ministry of Culture, including formal Islamic Guidance.

I left the essay unfinished, perhaps unintentionally. From those who agreed with the premise of the essay, the most common criticism I received concerned its failure to recommend a path forward: “Sure, but what should we do?” And indeed, there is the rub. How can one adopt a critical stance toward the occupation without feeding into yet another state of propaganda?

I did not have an answer to this question then, and perhaps I still do not. What is the language of critique when critical language has become a commodity itself— a salable object of desire that follows the capitalist logic of reproduction? Is critical language still critical if there is a market for it? And how much does it cost? How is it possible to speak about a territory which is even forbidden to gaze at? What do I know about Palestine when I cannot travel there as it is stipulated by my Iranian passport?

What happens to the image when it crosses the border? The fact that the article remains unfinished somehow states the impossibility of the situation. Palestine becomes a “phantasmagoria,” in a sense similar to what Walter Benjamin defined in his Arcades Project. It is a phantasmagoria of resistance—an object that is seen not in terms of its functional or financial value, but for its lyrical assessment and construction of a form of romanticism, or romantivism: romantic-activism. It is in the context of such a sentimental value that imagination comes into play, that is, in the fiction of a place where one has never been. The narrative that makes this sculpture a monument is a phantasmal geography of the other. In some way, phantasmagoria is not a micro concept here, but a primary state of mind: it is a grand concept that defines what things should look like, a fetish. Iran’s political role in relation to Palestine has become more that of a backseat driver, shouting unwanted advice or arguing against their actions.

Benjamin once said history breaks down into images, not into stories.25 But what profoundly confronts the orthodox understanding of the past—which Benjamin calls historicism—is that rather than finding its basis in the material evidence of the past, the explicit object of this new approach to history is not the missing past, but in fact the present. What institutes the materiality of the present is, undeniably, nothing other than the bricolage of all the aspects of the past that are conserved in the present. Thus, what he proposes constitutes an archaeology of the present. Iran and Palestine are two distinct geographies, and though they have shared histories, they remain distant from one another. Their only relationship is through representation and images, but these images alone are not enough to undo history. Is there a way to bring the art of storytelling back into such a hyper-politicized history?

The image of our collective past demands reinvention in order to confirm the possibility of thinking about social transformation, emancipation, and solidarity: an alternative way of thinking that entails an alternative method of investigation.

A version of this text has been previously published as a chapter of the book Three or Four Ir/relevant Stories: Art and Hyper-politics (2021).

- The conversation took place in 2015. However, the notion of “present” here refers to the time between 2015 and 2021 when I was working on the project. ↩︎

- The League of Nation’s Mandate for Palestine was a geopolitical entity formed in 1920, in the wake of the First World War and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The allied forces had promised the Arab residents of the Ottoman Empire their independence in exchange for their cooperation in dismantling the Empire and revolting against it. However, the British and the French had already signed a secret treaty, which later became known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, to divide the Ottoman lands into their own “spheres of influence”. Moreover, The British Government had declared its support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine and paved the way for the establishment of Israel by generous financial support, facilitation Jewish migration and suppressing Palestinian resistance. ↩︎

- Based on the descriptions of the Promised Land in the Book of Genesis, Arafat had claimed that the two blue stripes on the Israeli flag represent the Nile and the Euphrates and that Israel desires to eventually seize all the land in between. The use of the term became more widespread after the 1967 was to refer to the agenda of rightwing parties such as the Likud. This concept is sometimes called the Greater Israel. See:

Pipes, D. (1994) “Imperial Israel: The Nile-to-Euphrates Calumny” Middle East Quarterly. ↩︎ - Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) is a confederation of different Palestinian Groups which was founded during the First session of the Arab League in 1964. During the years this organization managed to include and unite a wide range of political and militaristic groups and therefore and rightfully become known as an umbrella organization representing Palestinian interests and desires. The creation of the Palestinian Authority within the framework of the Oslo Accords changed the nature of the PLO to a large extent. ↩︎

- Cooley, J. K. (1979) “Iran, the Palestinians and the Gulf” Foreign Affairs 57:5, P. 1017. ↩︎

- In the mid-70s some members from People’s Mujahedin of Iran (MEK) trained at Palestinian Liberation Organization’s camps in Jordan and Lebanon. See:

Goulka, J. (et. al.) (2009) The Mujahedin-e Khalq in Iraq: A Policy Conundrum, RAND Corporation, P. 56. ↩︎ - Parsi, T. (2008) Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States, Yale University Press, P. 85. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Parsi, T. (2008) Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States, Yale University Press, P. 86. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Entessar, N. (2004) “Israel and Iran’s National Security,” Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies 4, P. 6. ↩︎

- Parsi, T. (2008) Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States, Yale University Press, P. 88. ↩︎

- UNSCOP report to the General Assembly, Volume I (1947) which accessed via this link:

https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/703295?ln=en&v=pdf

The five states of Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia requested to add “The termination of Mandate over Palestine and the declaration of its independence” as an item of the agenda, but the proposal was ultimately rejected. ↩︎ - As it can be observed from the meetings minutes and the conversations of the committee members those who proposed partition were well aware the majority proposal would most probably not result in the establishment of an independent Palestinian, but they proceeded with this idea regardless of this fact. ↩︎

- From Mohn’s diary available via:

http://www.alvin-portal.org/alvin/view.jsf?pid=alvin-record%3A202&dswid=-3655 ↩︎ - The Tudeh Party of Iran, meaning the Party of the Masses of Iran, is an Iranian communist party established in 1941 with close affiliations to the Soviet Union. It had substantial influence in its early years and played an important role during Mohammad Mosaddegh’s campaign to nationalize the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and his term as prime minister. Tudeh identified itself as the historical outgrowth of the Communist Party of Persia. ↩︎

- The first Book of the Iranian Writers’ Association (1979), Tehran. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Reza Yasini (May 22nd 2018) “Interview with Niloufar Ghaderinejad” Iranian Labour News Agency. ↩︎

- See “Boris Anisfeld: A Wanderer between Russia’s Silver Age and America’s Golden Twenties,” written by Eckart Lingenauber, available at anisfeld’s website. ↩︎

- Nameh Mardom, (Mehr 5th 1389) No. 852 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- The Moscow-based publishing house Progress played a significant role by distributing inexpensive books in Farsi in front of the Soviet embassy, which helped familiarise many people with Marxist-Leninist philosophy, as well as art history and even children stories. Progress became a well-known publisher before the revolution. ↩︎

- Interestingly, while Fred Halliday was an Irish scholar, Mohajerani represented him as British. ↩︎

- Ibid, P. 476. ↩︎