I am 18 years old, looking at my new university’s impressively large and sumptuous building. I won a talent grant to study here, for which I wrote a lengthy application outlining various misfortunes and struggles I encountered in my short life that made me a perfect candidate for this award. I am looking at the building from the side, waiting in a lengthy queue leading to a white container with a door, not too different from the ones selling fries at the local market. Several faces I have seen in the lecture hall earlier that day passed by, slowing down next to me with curiosity.

What am I waiting for there?

Just something I need for my visa.

Visa credit card?

Something like that. I murmured through a forced grin on my face.

We queued.

We waited.

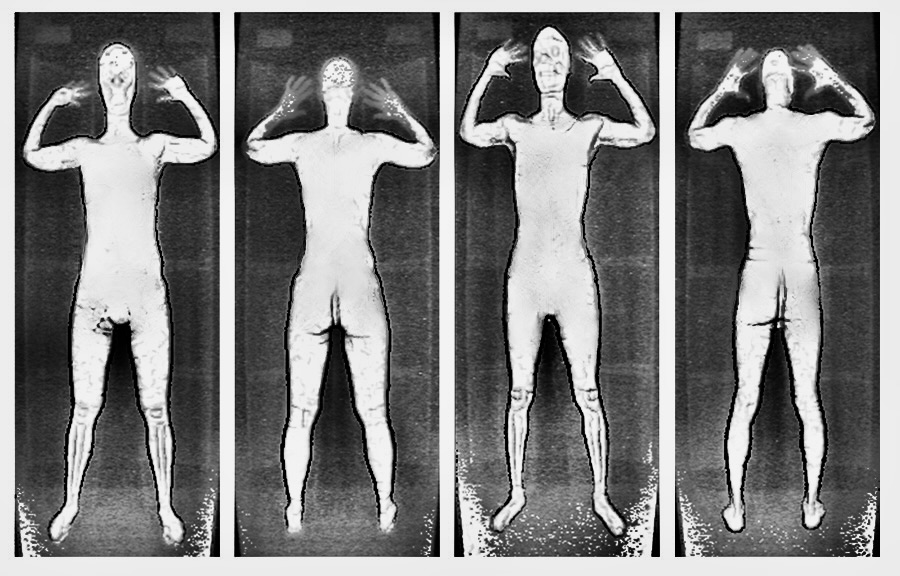

We stripped.

The X-ray machine made a dull clicking sound, which made me think of what I heard seconds before I felt the sharp pain of the breaking of my wrist bone once. But there was no physical pain that day. I walked out of the container and back to my student dorm, feeling exposed in layers. I was unaware I would go through the same examination many more times in the future.

The X-ray images of my chest are laying somewhere in public health offices across the continent. A transnational archive of the insides of our bodies is deemed risky to the public health of the civilised. I wonder if our images are stacked on top of each other in some basement of the hospital in Groningen while mould is painting flowers onto our bones. Are they melting into each other, forming one giant non-EU chest monster in the burning hot summer in the public health office in Thessaloniki? Did they separately stack them according to the degree of suspicion?

Did they care for those whose tests came back positive?

I have recently picked up a book which offers answers and opens pressing questions for those researching, experiencing, resisting and surviving technology-facilitated forms of violence. The book in question is The Gaze of the X-Ray: An Archive of Violence, published in 2024 by Transcript Verlag. It contains contributions from fourteen international authors offering various perspectives and forms of expression, including research-based essays, personal stories and reflections, fictional stories, archival images and drawings. These accounts are stitched together by the book editor, Prof. Shahram Khosravi, into a wholesome account of the history, desired potentials and violence inflicted and captured by the X-ray machine.

Reading the book made me feel uneasy and restless. The stories, the images, the ways letters are arranged and deranged by the page layout. The ways in which seemingly bland X-ray images of body-parts become haunting ghosts of violence inflicted on them (see Khosravi Noori, Sengupta, Abbasi Tavallali, Khosravi). The polka dots transform into bullet pellets; a hairpin is an eyewitness to the decades-long unpaid labour of the mother, a set of chest and naval bones evidence of the violent patriarchal gaze still haunting us (see Khosravi’s opening and closing chapter, Sengupta, Khosravi Noori). Nothing here is innocent, or how it appears to be, leaving the unsettling urgency to see the truths before our eyes without ever having to ‘look deeper’. This archive of words and images exposes the obsession of the powerful for controlling and seeing through the Other (see Krämer).

Although the stories told in this book are about the penetrating gaze of the X-ray, which enables us to see what was once deemed impossible, this book is mainly about the violence of what remains invisible. Because to this very day, some peoples’ pain is not seen even when the bone has made it through the flesh and skin (see Qasmiyeh). We urgently need the reverse X-ray goggles (see Favero) to enable us to see the obvious again. Detect the tumour of greed and extractivist colonial violence that, despite its omnipresence, remains invisibilised, ignored and left to spread at its own pace.

I was reading the book for weeks; I switched between its chapters in a hectic order, unable to stay still – the one thing the X-ray gaze once required me to be, to prove my right to exist, free from disease that could contaminate the entire university building, whose beauty I once so admired. Stillness is required for the X-ray image to succeed, which brings me to the aspect of this book which goes beyond the exposure of violence. It offers us the subversive view of resistance and rejection to stay still in the face of violence (see Sharif, Hillström &Tanimowo Okunseinde, and Noeth & Whalley). It offers us the joy of reimagining a world in which Du Bois’s Megascope and the authors’ R-5000 are invaluable tools that enable us to welcome back those rendered invisible, ‘ancestors and spirits who shaped our past, letting the fractures and scars speak’ (p.128). It is a machine that would listen carefully. That would believe our stories. That would care.

This book is part of the publication series Corporeal Matters, which ‘places the body at the core’. In times when the pain of Others is manipulated and erased on a daily, this book reminds us that our bodies will remain the everlasting archives. Archives of violence where the ‘truth’ which the X-ray tests are seeking to uncover is a simple act of psychological projection by the State: whilst the Other is deemed suspicious, carrying disease, potentially involved in genocide or terrorist activity (see Hussaini), this in turn tells us everything we need to know about the State itself. The ‘truth’ the X-ray is seeking to find in the bodies of Others is their own truth of ‘racial thinking and State surveillance: feeding anxiety, fear, obedience and humiliation to maintain bourgeois order’ (see Vergès, p.37).

Most strikingly, this book reminds us that our bodies will also remain the permanent archives of joy, refusal, and resistance.

Which will forever speak nothing but the truth.

Eva StefaniNational

Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens 2024

Eva StefaniNational

Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens 2024