On September 30th 1988, a wave of ethnic violence tore through the historical city of Hyderabad in Pakistan’s Sindh province. It tore through the fabric of a once multi-ethnic city, home to an indigenous Sindhi community, and a more recently arrived community of migrants who arrived there in the aftermath of the partition of India in 1947. A curfew was imposed for days on end, according to my parents and members of my family who lived in the city at that time. There was looting, attacks and rioting carried on for days. What remained in the wake of this event had wide repercussions that continue to affect the lives of the residents of the city, and even those who may trace their roots to it but have not called it home in decades. At the end of all this, what remained was a city divided. Sindhi people and the Urdu-speaking migrants found refuge in barricaded and separated neighborhoods, a division and separation that remains to this day. It was a separation, however, that had an inevitable impact on my family, where my father, a Sindhi, and my mother, an Urdu-speaking migrant, found themselves defending their family against the political fault lines revealed by the ethnic violence. A consequence of this defense was a loss of connection to history, heritage, and memory. They chose to look away from the past, and to never speak about histories. This was the world that I grew up in, silent, incomplete, evasive and made largely incomprehensible because even our culture and language was not given to us. This is the world that I want back.

The world is richer in its hybrids. – Aatish Taseer

Aatish Taseer’s words reflect my search for the hybrid, which is a search for the richer, a richer sense of the history of my family, as much as of myself. It is what Hyderabad has always been, a rich mix of people because of the many invaders and rulers that have come and settled here. It was once the beloved capital city of the Kalhoras and the Mirs of the Talpur dynasty. The city was founded in 1768 by Ghulam Shah Kalhora who chose this place because of its access to trade roots. He placed a military garrison here. It was not until the British arrived that the city lost its status as a major economic, military and cultural hub to the fast growing city of Karachi. A rich mix of communities, ethnicities, languages and faiths could be found here. Until that afternoon in 1988, this hybridity, this plurality, this mongrel-ness was also my history and my identity. Having been born and raised in this unparalleled region has given me a sense of discomfort and insecurity of my roots in this land.

This project is about untangling my hybrid identity. It aims to find the elements of my identity which links me to this land. It is equally a retracing of my own roots as it is a desire to rediscover those sides of my heritage that were erased, hidden or forgotten. The project is a history of a wounded city, as much as it is a history of a wounded family. We never spoke about the past, but the scars of those events continued to have their reverberations within families like mine, those who decided to leave this city decades ago and those who decided to stay. As I search for stories of the aftermath of these riots, I search for myself, and that which remains of a world that I feel within, experienced surreptitiously within the walls of my family home, a world that remains silenced and hidden. In the story of Hyderabad’s aftermath, under the shadow that still hangs over the lives of the people here, is my story. At least, that is the hope that inspires this work.

Since childhood, I have been told that I was born on a sacred soil, rich in culture, literature, and heritage. But in a new city like Karachi with a higher literacy rate and said to be more civilized than the rest of Sindh, I started witnessing the differences created based on language and culture.

Born to a Sindhi father and an Urdu-speaking mother, I call myself a hybrid daughter to this land. My family moved to Karachi When I was seven-years-old. This project is all me, tracing footprints of my family, visiting memories, asking questions and searching for answers only to rediscover my lost roots in this land.

People of Language

The memories from my childhood narrate that my brother and I were raised bilingual. My family from my father’s side is more open to different languages and cultures compared to the city of Karachi, where I was raised and is considered to be more diverse and open.

Rita Kothari beautifully sums up this whole disconnection between me and my roots in her article, “The Persistence of Partition” (2011): “For this third generation, Sindhiness is a cluster of undesirable traits and the easiest way to distance oneself from them is to refrain from speaking Sindhi – the only historical marker of this linguistic identity.”

And that is what I did.

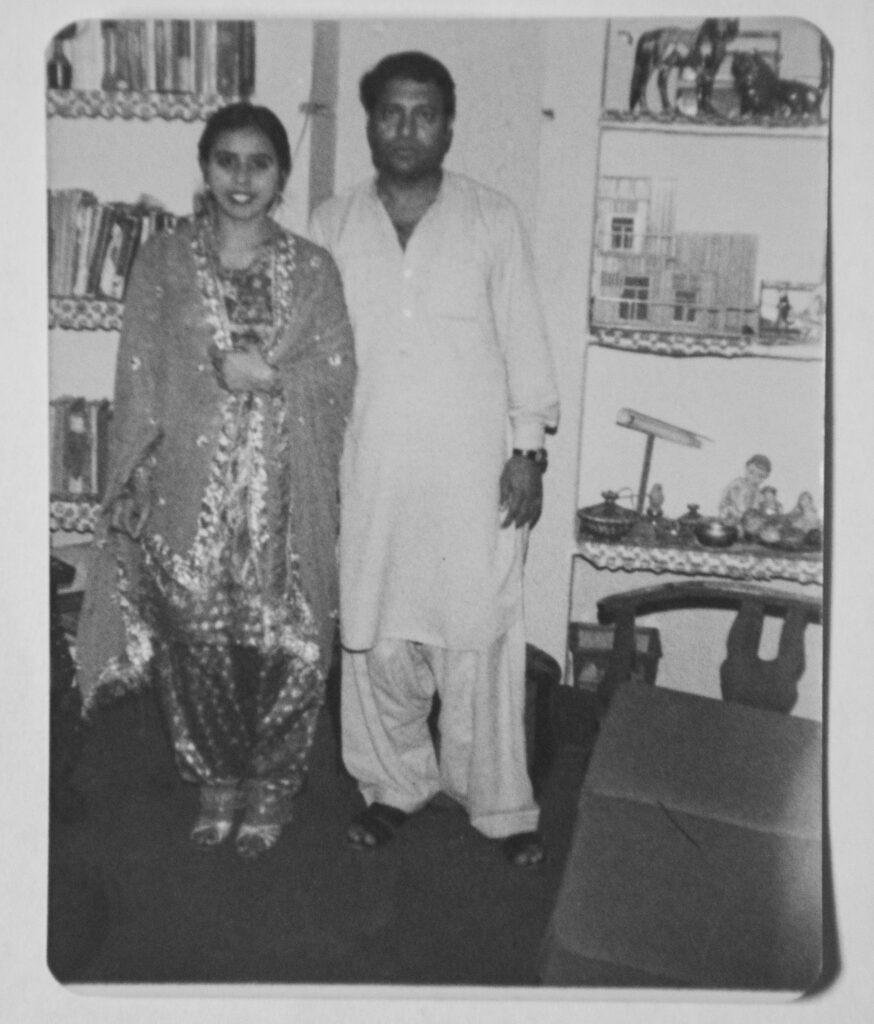

My father and mother on the next day of their wedding in Gari Khata house

I stopped speaking Sindhi – stepped back and ignored my roots and culture in order to best fit in. Somehow, Urdu stayed alive in our life as it was a common language spoken between my parents, while Sindhi slowly faded away.

My Connection or Disconnection

A complete family portrait, my parents, grandmothers, uncles and aunts

“On the departure of the British, partition of the country and creation of Pakistan, refugees (Muhajir) immigrated here, settled down and have socially adjusted themselves with the local people, so much so that apart from leaving the Sindhi language, there have been many inter-marriages at several levels of society.” – G.M Syed, Sindhudesh

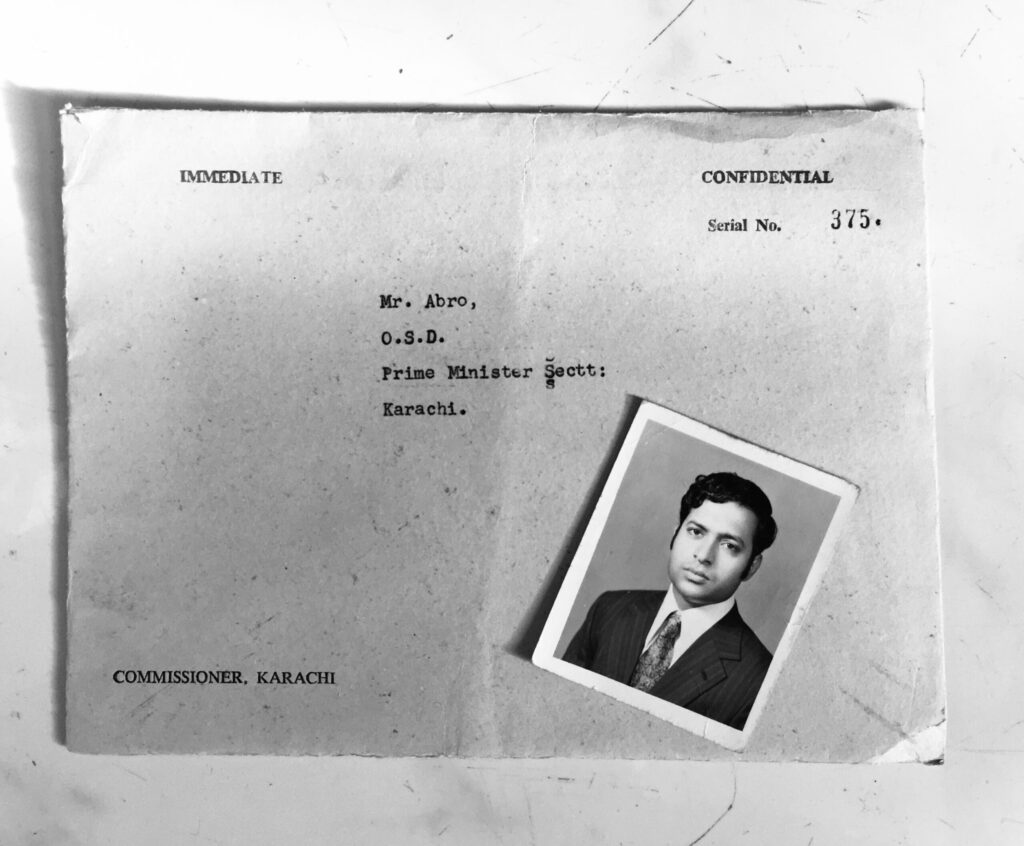

And my family is one of the examples of the inter-marriage which G.M Syed mentions above. My mother belonged to an Urdu-speaking family, migrated from Delhi, and settled in Karachi after partition. My father was from a Sindhi-speaking family based in Hala, a small town near Hyderabad. He along with his other siblings has been raised in Hyderabad. My father was an advocate by profession. He served as an Officer on Special Duty to then Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

While working as a government servant, my father met my mother’s brother and they became close friends. So, it was all quite normal, a Sindhi coming and hanging out in an Urdu-speaking household. No tug of war on languages or culture whatsoever.

My parents got married in 1980. During that time my father’s home was in Gari Khata neighbourhood, in the old city of Hyderabad. From there, they moved to Latifabad, Unit 5. And I was born there in 1985.

My parents with aunts and uncle in our old Latifabad house

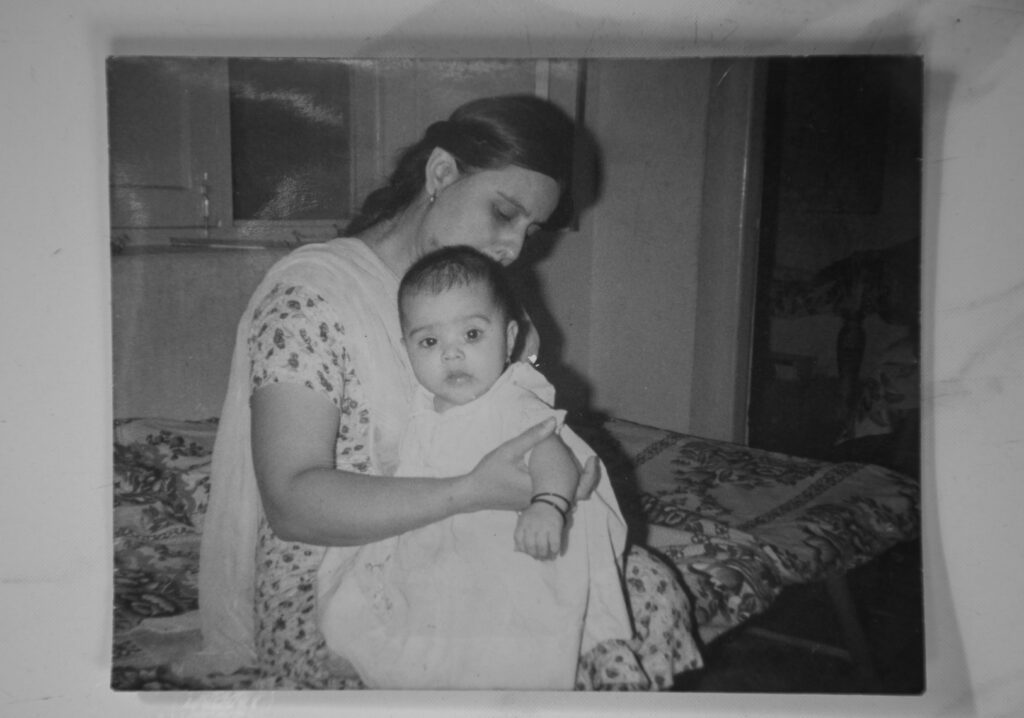

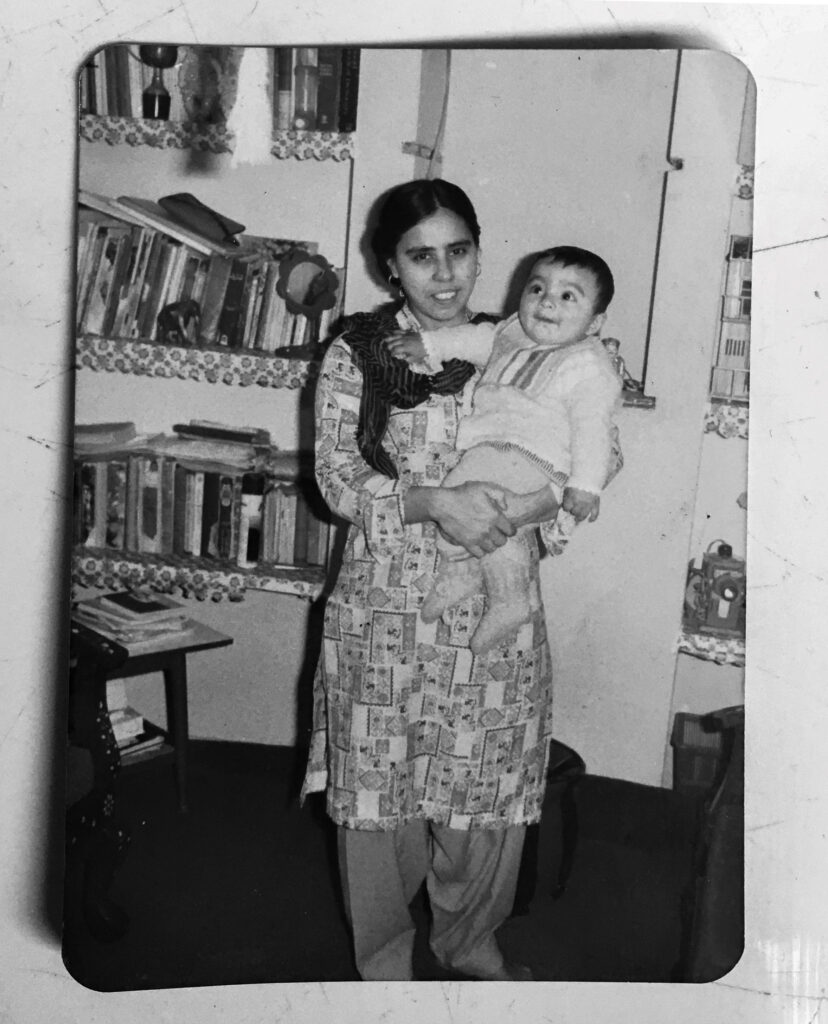

Eight-months-old me with my mother in the old Latifabad house

During my school days, Sindhi-Muhajir clashes were at their peak. In school, I was asked: “Who are you? What is your caste?” In social settings, we were discouraged to speak Sindhi, but only Urdu or English. So, I began questioning my identity.

I have witnessed these differences not just on a social level, but in both the paternal and maternal family environments as well. So, I started asking my father about the connection I have with this land. Did this soil, this land, always had these differences and this war of belonging. When did it begin and why?

My parents and I in our Qasimabad house

Pictures starting from Left:

My parents on their wedding reception in Hyderabad

My mother and aunt standing in the garden of Latifabad house

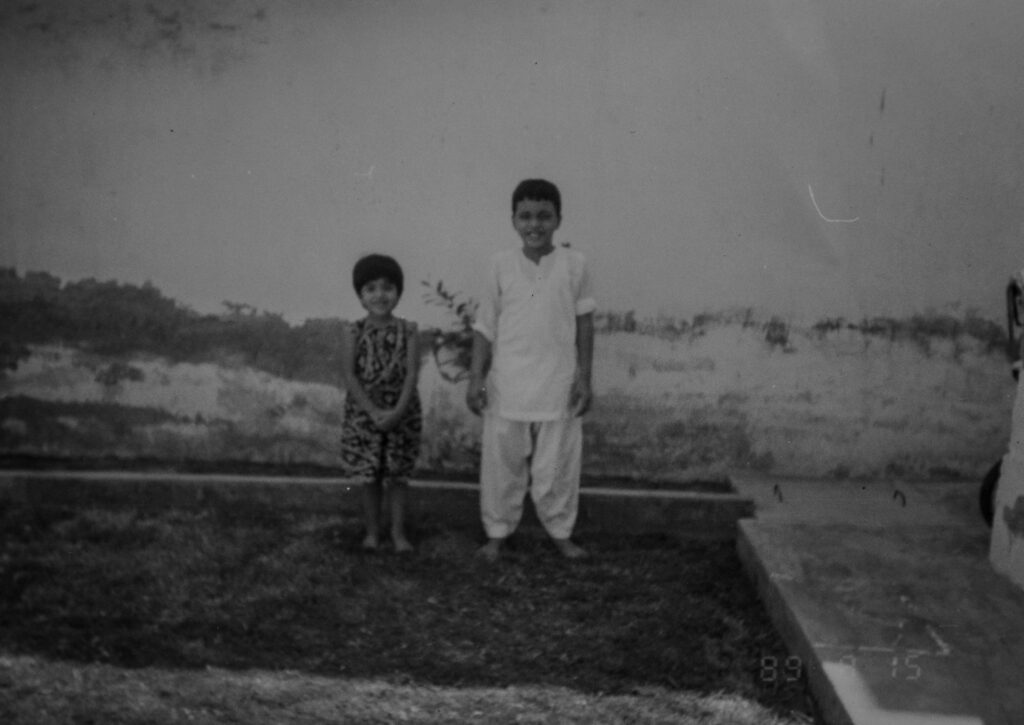

Me and my brother in Qasimabad house

My mother with my brother in Gari Khata house

My journey started in two directions. One path leads to tracing the footprints of my own family, starting with my birth city, Hyderabad.

And in the second path, I try to understand the link between language and land by understanding the lives of people, that is the speakers of the two main indigenous languages of this land, Urdu and Sindhi. Is my connection to this land and with these people only limited to the language we speak or does it go beyond the significance of language?

The view from Mir’s court inside the Pakka Qila (fort) in Hyderabad

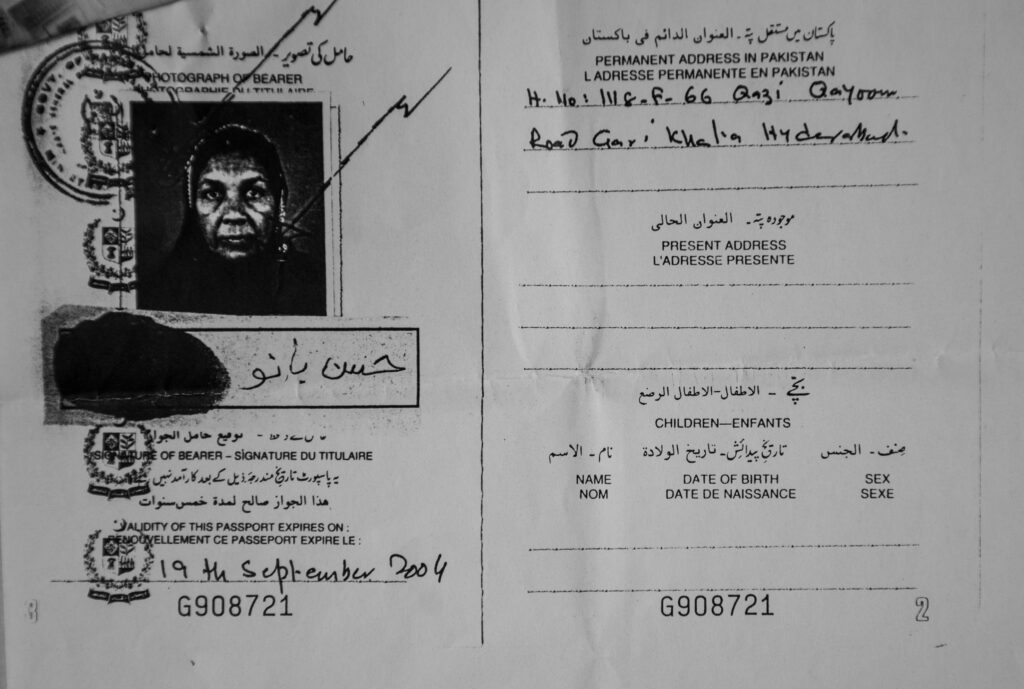

My grandmother’s passport copy stating the old address of Gari Khata house

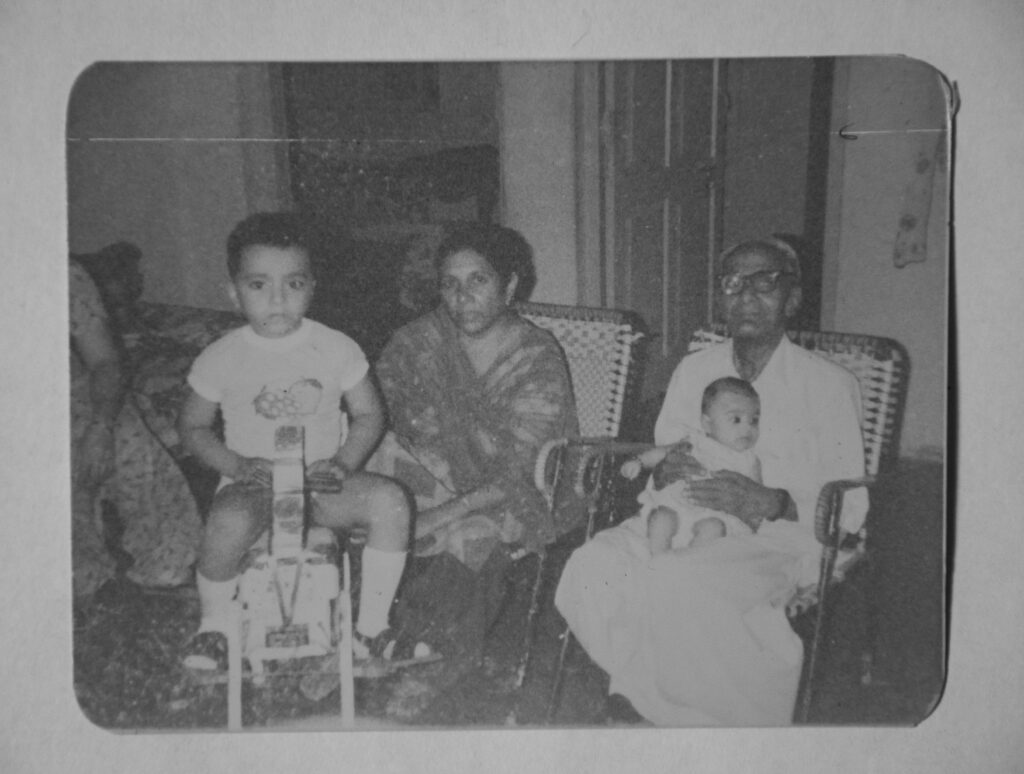

Me and my brother with my late grandparents in Latifabad house

An old governmental envelope with my father’s name and passport size portrait which I found in his old briefcase

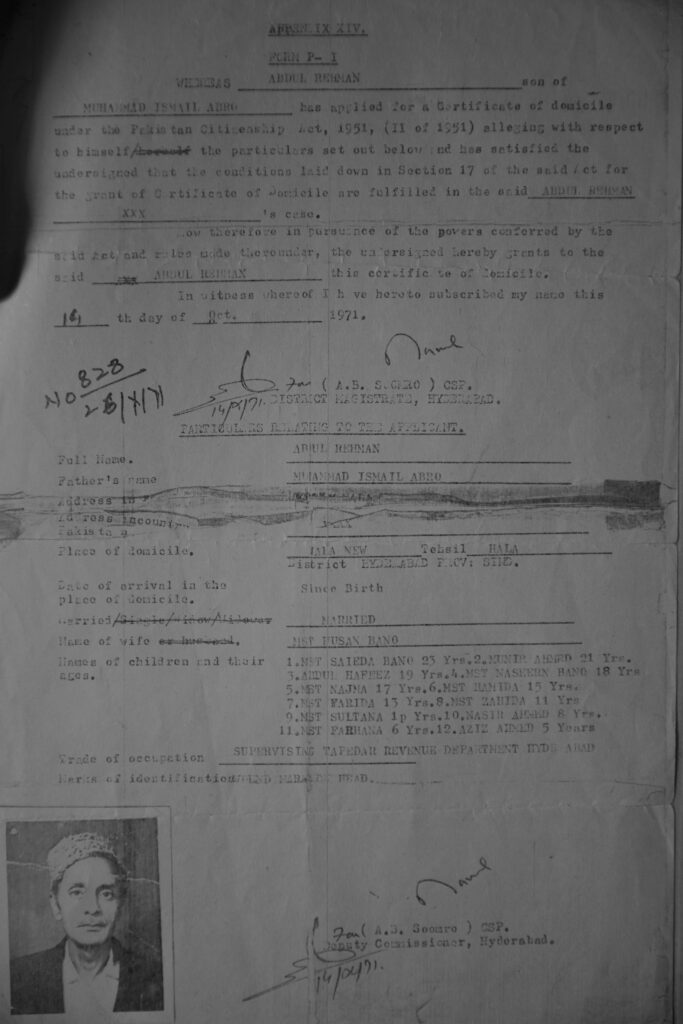

The oldest piece of family document: my grandfather’s certificate of domicile

Where I was Born

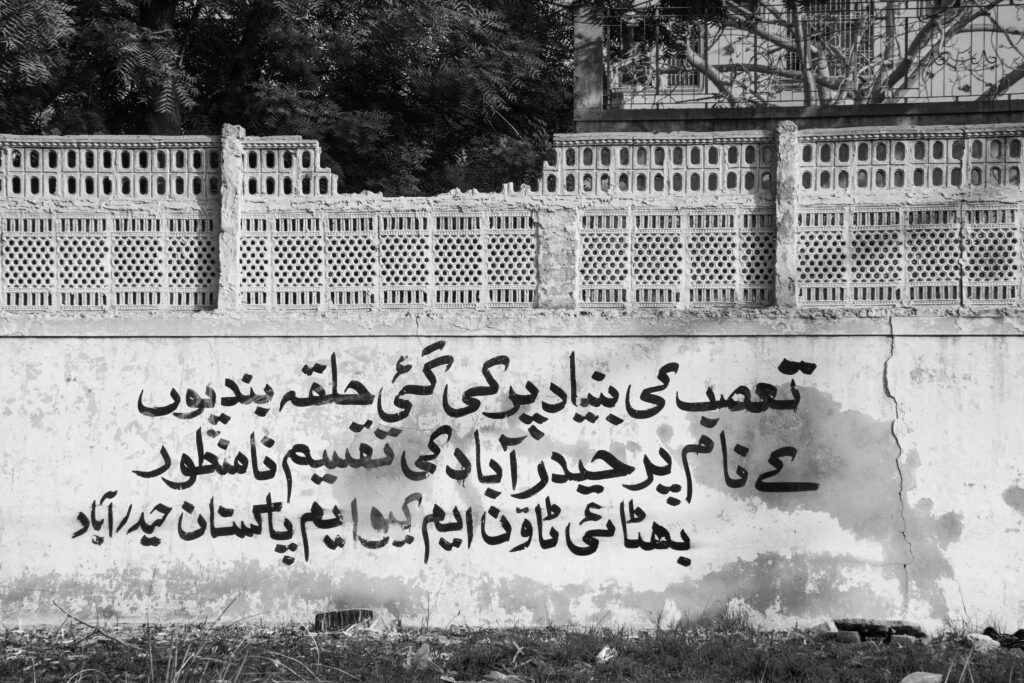

The house I was born in is located in Latifabad, No. 5, close to the river bank. As my aunt and I entered the vicinity, it made me feel like I’m visiting Liaquatabad or any other Urdu-speaking area in Karachi. There was a wall chalking which I could not help but notice. It was not so old and spoke of the unfair division of Hyderabad based on ethnicity and how it is negatively viewed by one of the political parties belonging to the Urdu-speaking community.

“Division of Hyderabad on the basis of ethnic enmity is not acceptable” – Bhittai town MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement, a secularist, social liberal Muhajir political party)

A tea stall near the house of Latifabad

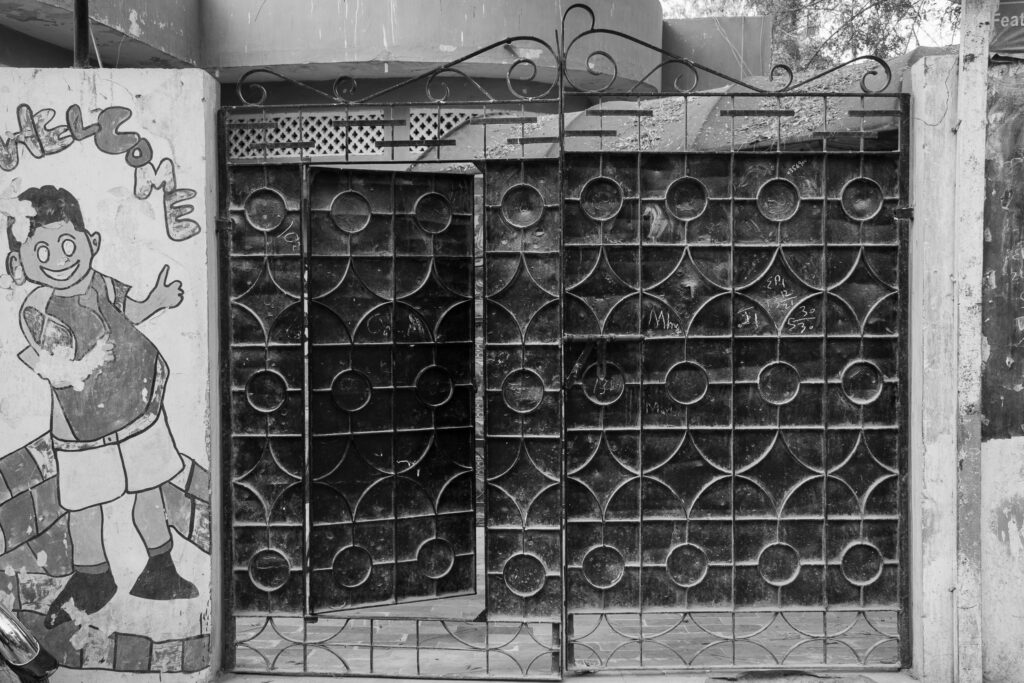

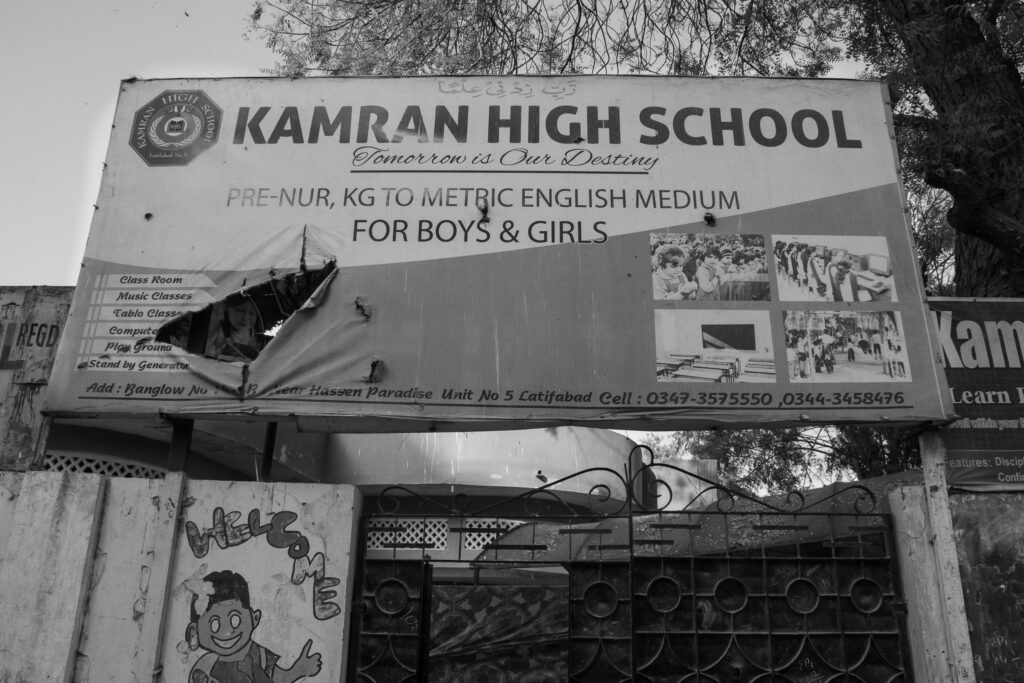

We tried to trace the landmarks with the help of my aunt’s memories and reached a wide lane, a Chai stall in the corner, a closed office-like building and a black gate adjacent to it which looked like it would open to a house, but there was a school signboard above it.

The main gate to the house with the school signboard

The entrance to the house which is now a school

A mirror door to a small room near the main entrance

The door was open and we could hear the enchanting voices of the kids inside. It was almost evening and the kids were there for tuition after school hours. We stepped in and saw two ladies in their early 40s tutoring the kids. We explained why we were there and that we just wanted to see the house from inside and take a few photographs for memory. They refused at first, but then I remembered carrying a digital copy of an old photograph of the house, in which my father and mother along with my aunts and uncle are sitting right on the rounded entrance steps, at the same spot where the teacher was standing holding a book.

We somehow got her to agree to giving us a little tour from inside.

Above is the archival image of the entrance and below is the most recent image of the same entrance

Most of the rooms were locked and there was no light there. The back of the house was inaccessible as well, but to my astonishment, there was enough to spark my aunt’s memory who recalled every detail of their lives in that house and as we walked from room to room, she told me who slept where, how the stoves were placed outside the kitchen where my mother used to cook in summers, and how my brother used to peddle on his tiny bicycle all over the outside corridor. The trees of custard apple, lemon, and papaya covering one side of the house were no longer there. There used to be a garden in the front, which was now replaced with a tiled floor. The stairs leading to the roof were now blocked by rustic furniture and were off-limits.

As my aunty recalled: “the doors and windows are still the same, even the floor inside the rooms is the same. We used to have a garage at the back of the house and a back door. It was a very peaceful time. We used to play and go to school and college from here.”

The main room, which my aunts used to share, with doors to other rooms belonging to my grandparents and uncles is now a classroom

.My aunt tells me that the door and windows as well as inside floors are still unchanged. This door used to open to the kitchen corridor

A broken chair in one of the empty corners of the house

The side of the house which leads to the backyard was once filled with trees; papaya, lemon, custard apple.

A view from inside into the former garden area. My mother tells me it was a lush garden with lemon and roses, and money plant.

I noticed irritation and agitation on the faces of the two teachers when my aunt spoke to me in Sindhi particularly. I could not help but notice the disapproval in their gestures and expressions. They even asked me at one point not to take any more pictures of the house from inside. So, I kept my camera away on my shoulder while I tried imagining the better old days, my father, mother, brother and grandparents and the rest of the family had in this very house. I tried listening and absorbing every sight of this house as my aunt kept sharing pieces from her memory. But later, I could not help but wonder, if the reservation was because of our visiting suddenly in the middle of the day or the fact that we speak Sindhi.

Bano, Nani & Me

A view of water tower from fort ground inside Pucca Qila

As I started asking questions from my family and others, I realized I was lost in the debate about political actions and the issues distribution of land and language and that barely no-one understood what I was seeking, including myself. The questions were simple, but even I at that time was unable to put them in the light clearly. While I was juggling between thoughts, I decided to sit with random Urdu-speaking families and understand that side of my heritage. My path led me to the people living in the old town of Hyderabad, Pucca Qila (Fort), a post-partition Urdu-speaking settlement.

A view of the fort wall from inside

And there I met Bano.

During my first visit, she did not say much, but when my visits became frequent, Bano let the story of her life float in front of me. It was a breezy afternoon, with the sun slowly taking its turn to set and its light creating dramatic shadows through adjacent houses and the things which caught the light in between. Bano and I were standing on the roof of her house, when after a little pause she started sharing her story of belonging with me.

She told me about the place where she grew up, not far from the fort area. A place where both Moharram processions and the urs, or death anniversaries, of Sufi Saint, Khwaja Muin al-Din Chishti, were held with great zeal and respect.

When I told her about my being Sindhi from my father’s side, she said there were many Sindhi families living in her childhood area and how they used to eat and play together, just like a family. But now most of their daughters have been married off into the village. Due to the Sindhi-Muhajir conflict, almost everyone has gone back to the village.

A view from the roof of Bano’s house

Banoo’s clean and tidy room reminds me of my mother and our small apartment in Karachi when we moved there.

I spent many afternoons, listening to the memories, stories of their children and the hardships they had endured throughout their lives. Gradually, I began to see certain similarities that Bano and I shared in terms of belonging to a particular ethnicity.

One afternoon as I entered their home, Waqar bhai, Bano’s husband, was patting his hand dry with a towel. He gestured me to come and sit inside. “You roam around all day; you need to eat. You need to have energy. Come have some food with us.”

As he unfolded a dastarkhuwan, a tablecloth, on the floor, Bano brought me a hot plate of Qorma (chicken stew) made in typical Dehli style. The aroma instantly took me back to my grandmother’s kitchen.

I asked her who had made the Qorma and she said one of her friends who also lives in Qilla (fort) cooked it for Giyarwee Shareef[1]. She then added, in a hesitant tone, that their limited means have kept them this year from making Qorma (chicken stew) and Kheer (rice custard) on this Urs, and so she has made some Poori (fried bread) and Aloo Tarkari (Potato Curry) in celebration.

Sheharyar, Bano’s son, along with her husband, Waqar

I remember having heard this name, Ghous-e-Azam, from my Nani and my mother. My Nani used to make a special meal on Giyarwee Shareef and do Fateha and distribute food among the neighbors and needy people. It was almost like celebrating Eid. We were asked to wear new clothes and the woody-flowery fragrance of Agarbati, the incense burner, filled the house.

And now, hearing this name again from Bano makes my heart warm as it brings back sweet and delicious memories: my Nani’s kitchen all lit, the aroma of cardamom and spices dancing in the air and the food cooked with nothing less than love. Qorma (chicken Stew), Kheer (rice custard), Daal ka halwa (lentil’s sweet dish).

Aloo Tarkari with Poori

An afternoon with her busy in her kitchen

“You remember I told you that we celebrate urs on our Juman Shah’s pir? We use to celebrate Giyarwee Shareef like a festival when I was young. I learned to cook from my mother. I took admission in a sewing class near home but my mother fell and broke her arm so I had to learn how to cook. We, Urdu-speaking folks, cook everything at home. No matter how many guests you are expecting, back in those days, everything was cooked at home. And once my mother told me if you want to win your husband’s heart, then learn to cook delicious dishes.”

As she paused, there was shyness on her face while she corrected her scarf and looked at her husband who was sitting by the wall with a warm smile on his face. She gracefully stood up and went into the kitchen.

Bano and Waqar bhai sharing a moment before tea time

Bano making round chapatis for lunch

Before I could control my nostalgia over the exotic aroma of Qorma, she handed me freshly made hot chapati (bread). I asked her if she also uses a domed pan to cook chapati like my Nani and mother. She told me, yes but nowadays she uses a flat pan as well.

That afternoon our conversation took us to the shared food culture between her ancestors and mine. “kya aap mix-sabzi bhi pakati hain?” (Do you also cook mix-vegetable stew)

She laughed and said: “Bawli Bhujia- haan humare yahan usko bawli bhujia kehte hain. Sab sabziyan aik saath pakti hain to bawli hojati hain isliye hum bawli bhujia kehte hain usse.” (Yes, we call it Crazy Vegetable mix. When all vegetables are cooked together, they look crazy so we call it crazy vegetable mix- Bawli Bhujia in Urdu)

Sharing a laughter during afternoon gupshup

Everything which needs to be stored for later use is kept in this small space.

A moment in the afternoon light, sharing stories from yesterday, smiling at today.

Footsteps or footprints. Her slippers mark her presence in this very home

.The only chair in her home, kept in a corner, waiting

Monologue

When I started this project, I did not know where I was headed with all that I sought. All I knew was this would be a long, nerve-wracking task. The photographs, the text and everything else was my first of the kind. I come from a family that is not religious in readings and/or visual art, so my findings, struggles, and the path are all defined by my exploration.

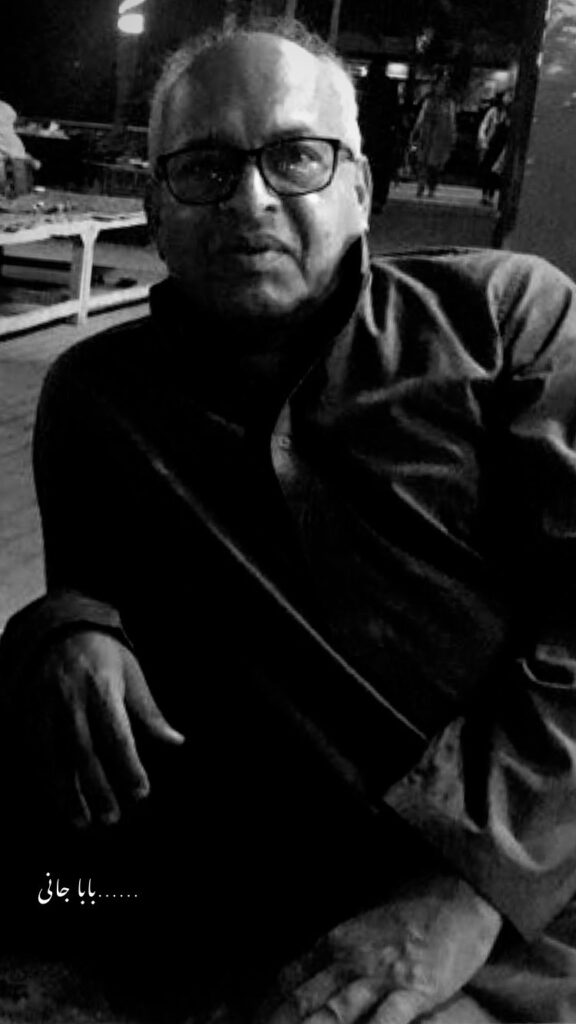

My father was alive when I under took this project for my fellowship. And the idea of giving my doubts and disconnection a shape of a long-term photo project, came from my years of long conversations and arguments with my father. So, this project became more like a personal journey.

Even if we are unable to speak, we can listen and register most of what is said or spoken. Our senses are very strong and even in the time of our worse illness, our brain does register everything in its consciousness. My father during his last days was unable to speak and had no energy to even listen. But we kept the conversations going; me with very few words and him with silence. I kept him updated about my project and struggles with it. The most he did was nod in acknowledgment, and even that was enough for me. His presence was enough for me to keep going.

Back in the days when I selected this lost identity as my project, I was skeptical because it was not just my journey, but it was OUR journey; my father and mine. Our conversations, his stories, my doubts, and our hybrid living which has led to this. So how come I can do this all myself. With his rapidly deteriorating health, I was unsure of this path but his presence was enough to keep me going, keeping him updated, knowing that he knows and is aware of my progress- it kept me somewhat sane. But three months into the project, as the new year dawned, I lost him. The foundation of this project was gone.

Munir Ahmed Abro (1950-2022)

[1] A cermony or Urs to commemorate the death anniversary of Sufi Saint Sheikh Abdul Qadir Gilani also known as Ghous-e- Azam by his followers all through the Indian Sub-continent.