An Interview with Samaa Emad Abuallaban

Why do we read about Palestine? Why should we read about Palestine? In exploring the geography of the region, Sarazad has consistently focused on the history of Palestine and its complex political and social dimensions since the inception of the website.

As we dreadfully observe the genocide and the ongoing occupation of Palestinian land, we believe that understanding power structures, colonialism, methods of occupation, and the struggle for independence is crucial for comprehending broader issues of justice and social struggle.

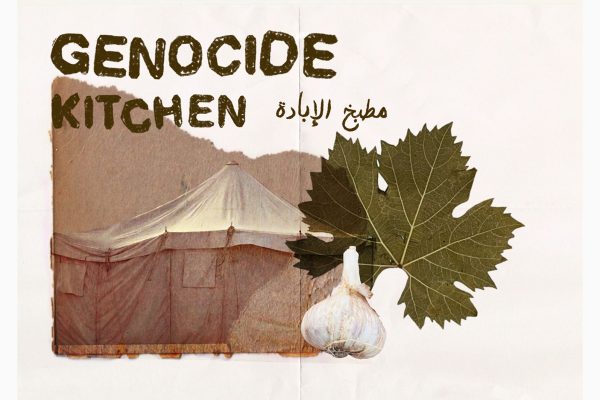

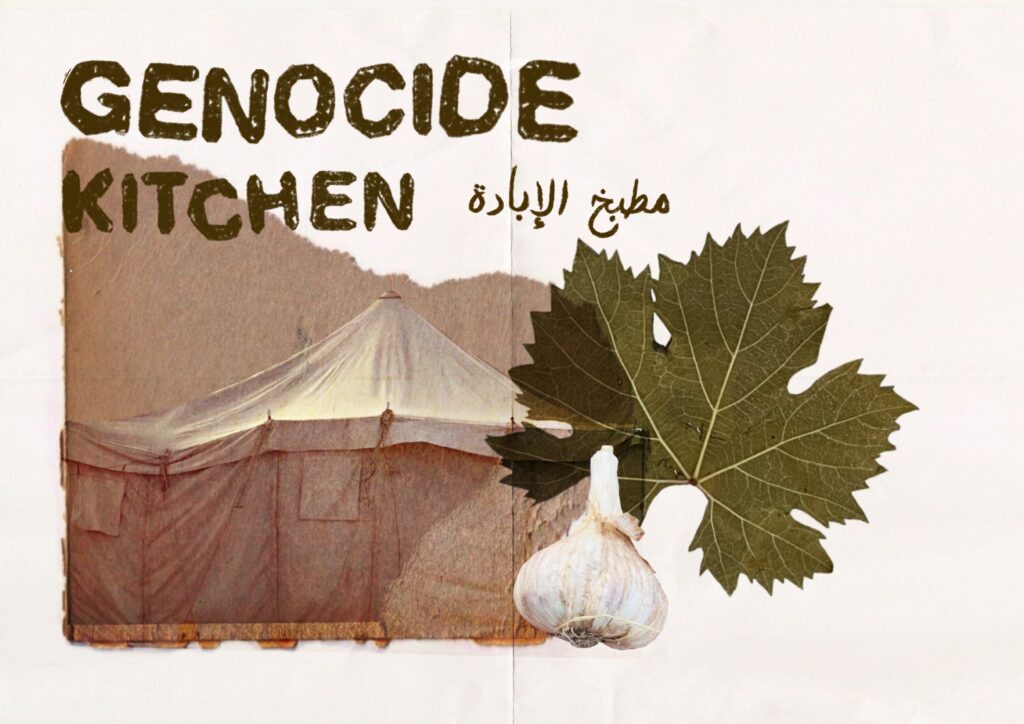

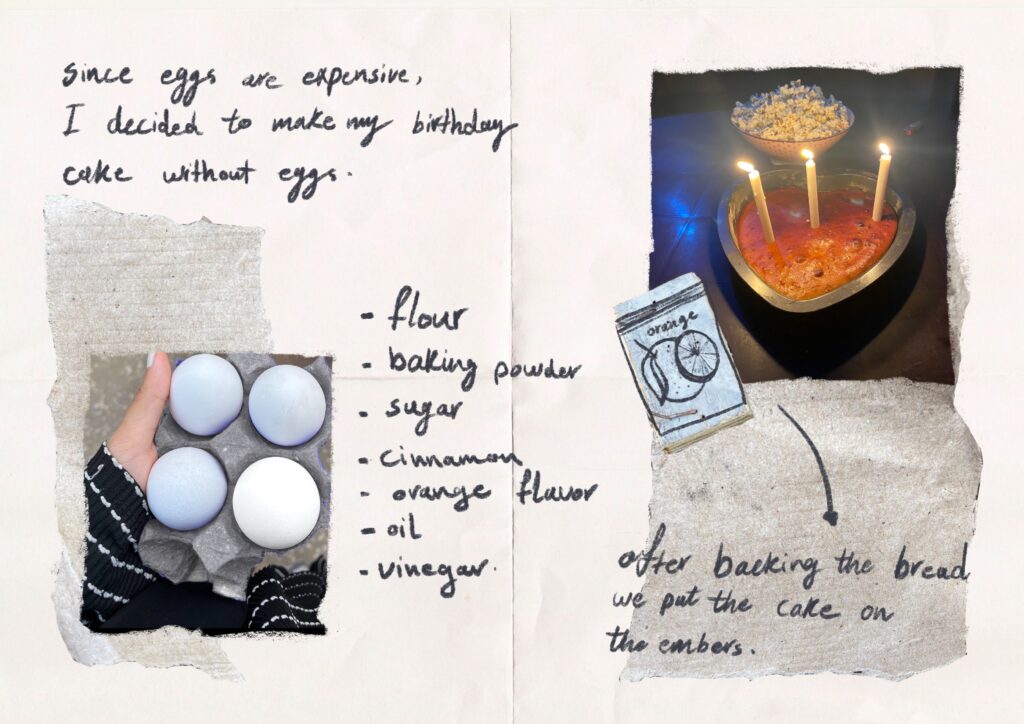

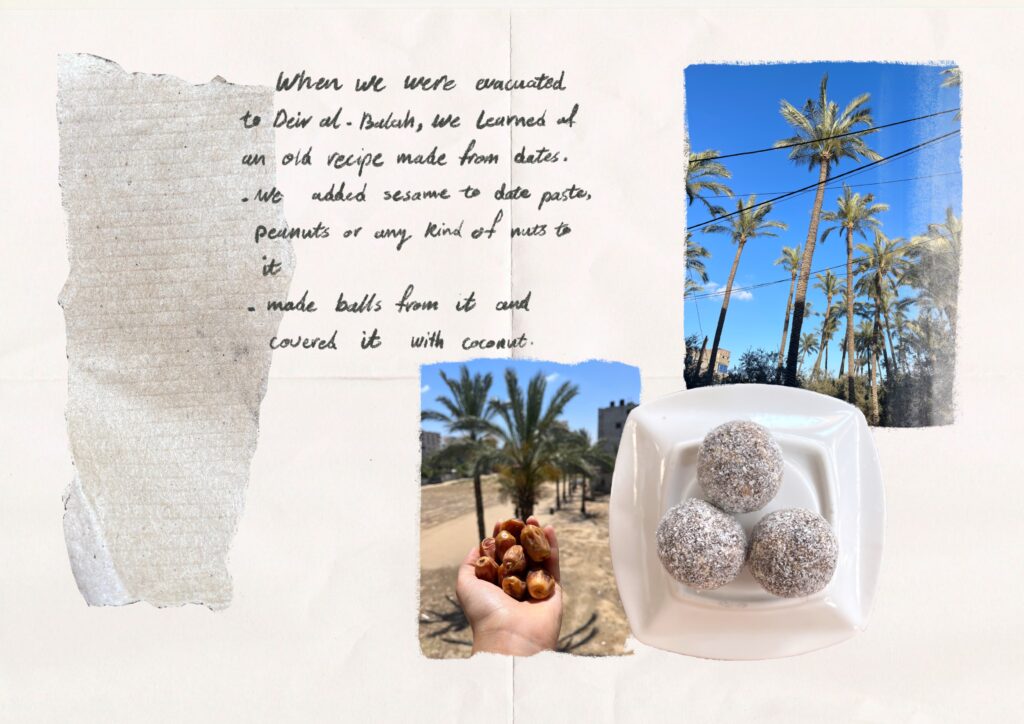

Amidst the violence, what often goes unnoticed is the persistent flow of life that continues unabated, insisting on survival under the shadow of genocide and exile. The Genocide Kitchen project exemplifies this resilience, capturing the act of cooking during times of genocide and siege through a series of collages.

Samaa Emad’s collages are deeply rooted in concepts of time and place. In this project, her identity is not presented through direct narrative, but through the act of cooking and everyday actions that form the core of daily life. Here, resistance takes on a new meaning. Is not the essence of being alive_ of living and embracing freedom_ the most fundamental definition of being human? Through its simple and quiet narrative, Genocide Kitchen serves as a poignant reminder of freedom and liberation—the very essence of life that has been systematically eroded in Gaza for years.

Sarazad: Could you please tell us a little about yourself and how you became interested in art? What kind of art education have you received? Which artists and works of art have shaped your view of art?

Samaa: My interest in art has its roots in my childhood, but later in life art also became a means of changing and influencing society for me. I believe that artists can play an important role by expressing their ideas, opinions and feelings. I studied graphic design and specifically chose collage as my method of expression, which was a decision influenced by local artist such as Mohammad Jeha and Hazem Harb who have used collage in their work.

Sarazad: Could you tell us a bit more about your art school? We can assume that your reader might not know much about the structures of art education in Gaza and a description may help them understand life in Gaza better.

Samaa: I have a Bachelor’s degree in graphic design. Our program offered a combination of computational programs and manual art techniques, which equipped me with design as well as many fine art skills. In Gaza, there are only two universities open to those who wish to study arts or design and so most artist know each other either though school or from work spaces where they gather, where their works are collected and activities such as artistic workshops take place. Many of these centers and gatherings have helped me to talk about my art work, see other people’s works and gain new and diverse experiences. The artistic community is Gaza is small, but in it we find a safe space to express our reality in our own way and talk about what goes on in our heads.

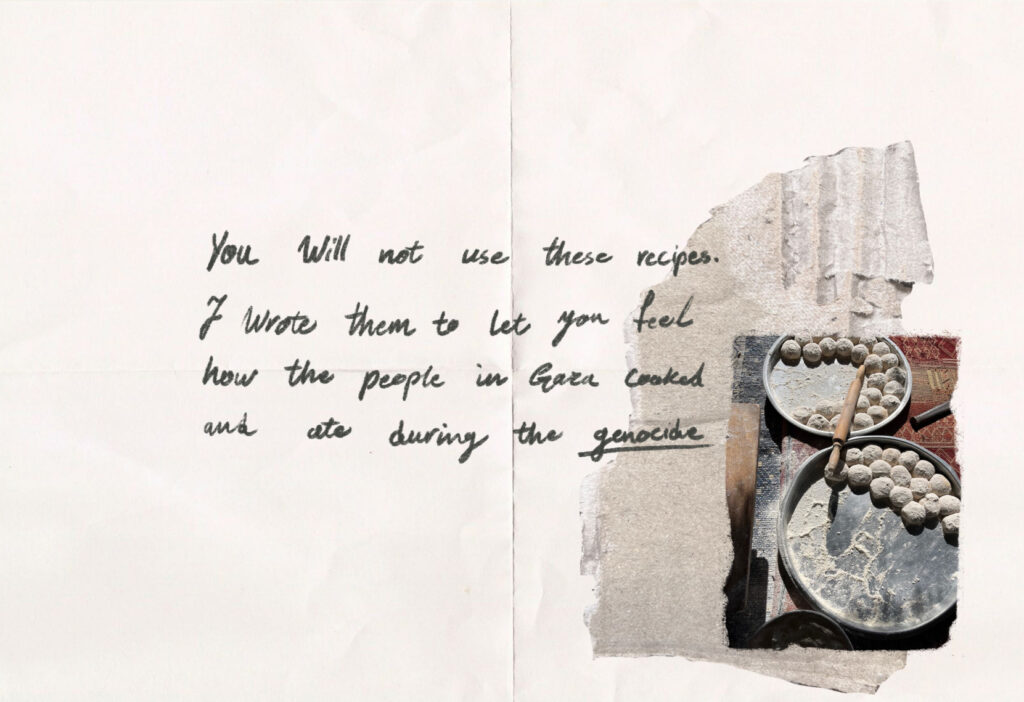

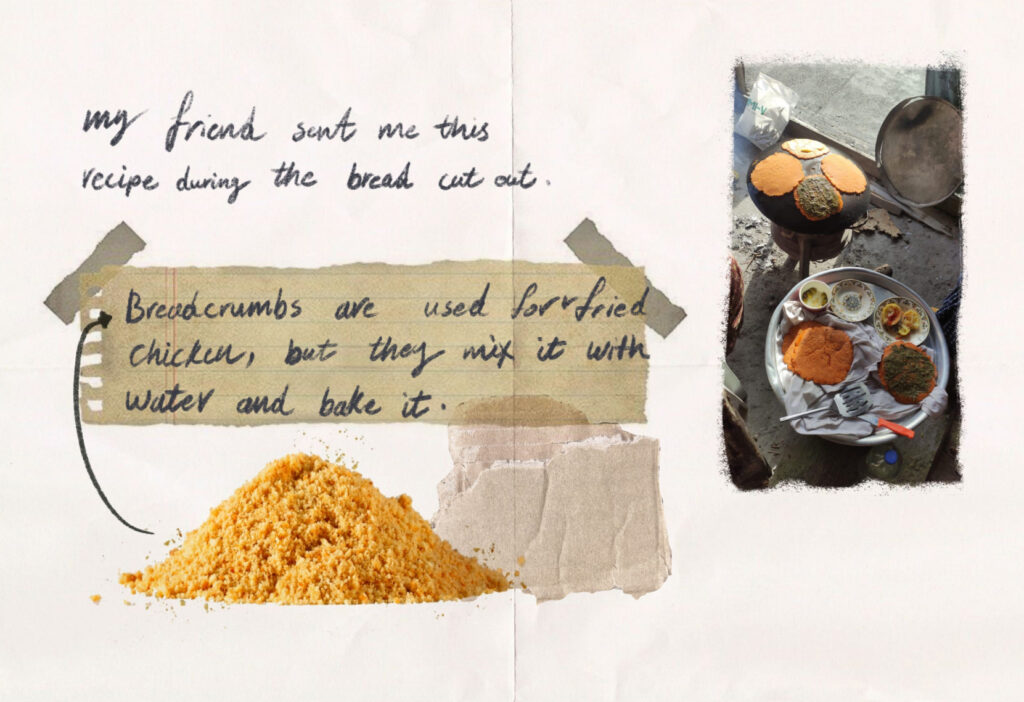

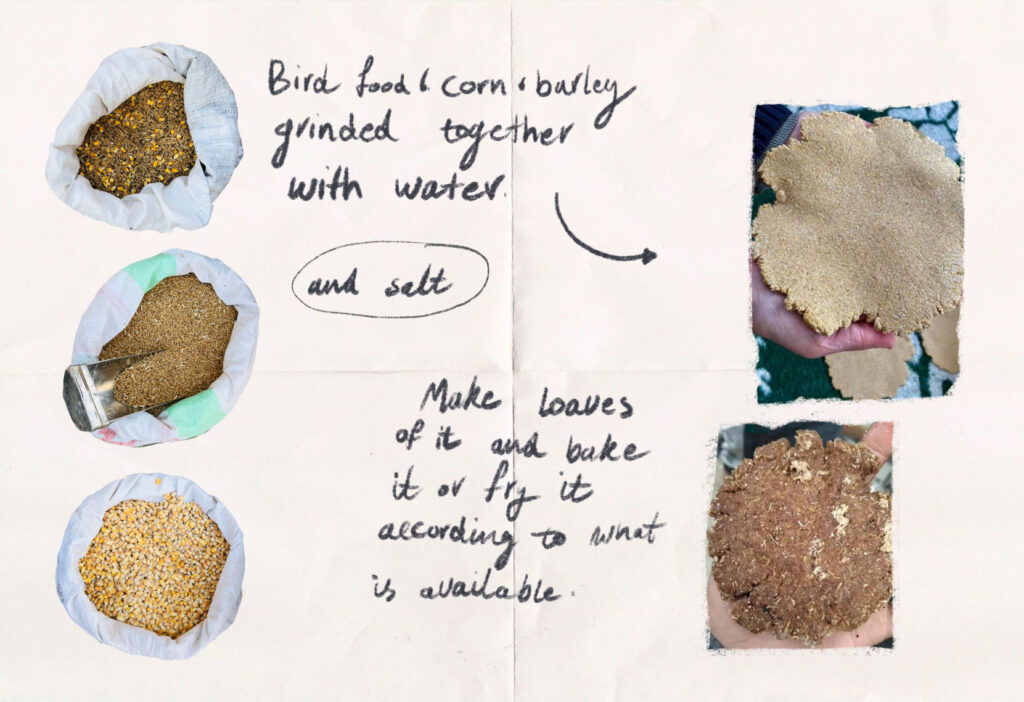

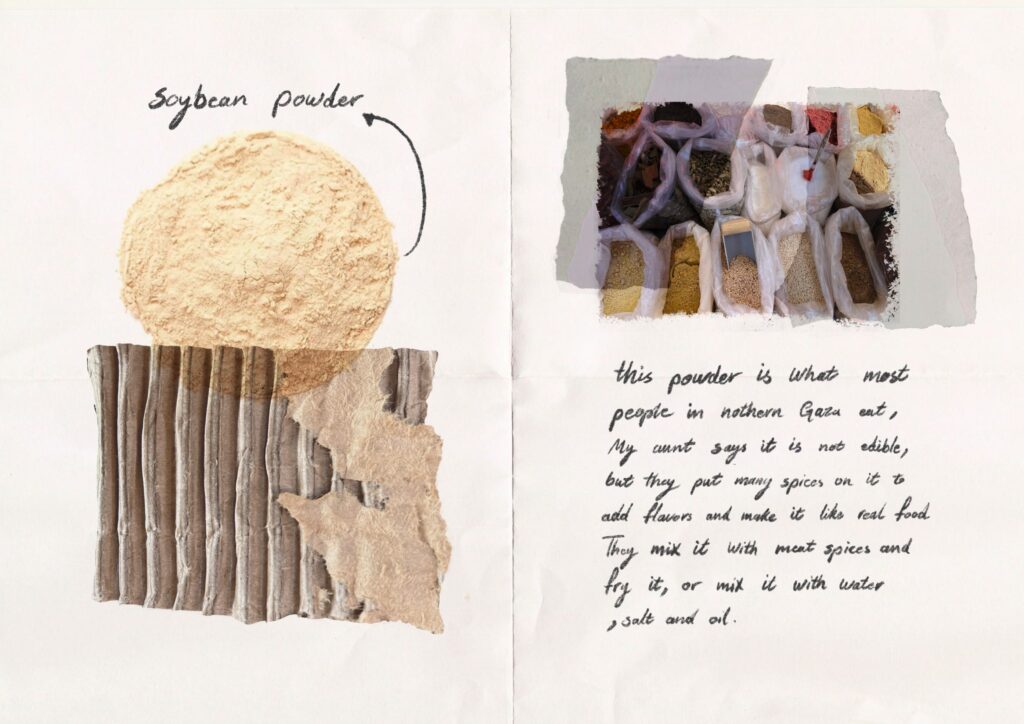

Sarazad: You start The Genocide Kitchen with the sentence: “[t]hese are recipes you’ll never use.” The sentence reminds the reader of how cooking as a daily activity is different from cooking in the middle of a genocide and under forced starvation. Why did you think that you need to focus on food and food preparation methods? What has happened to agricultural lands in Gaza?

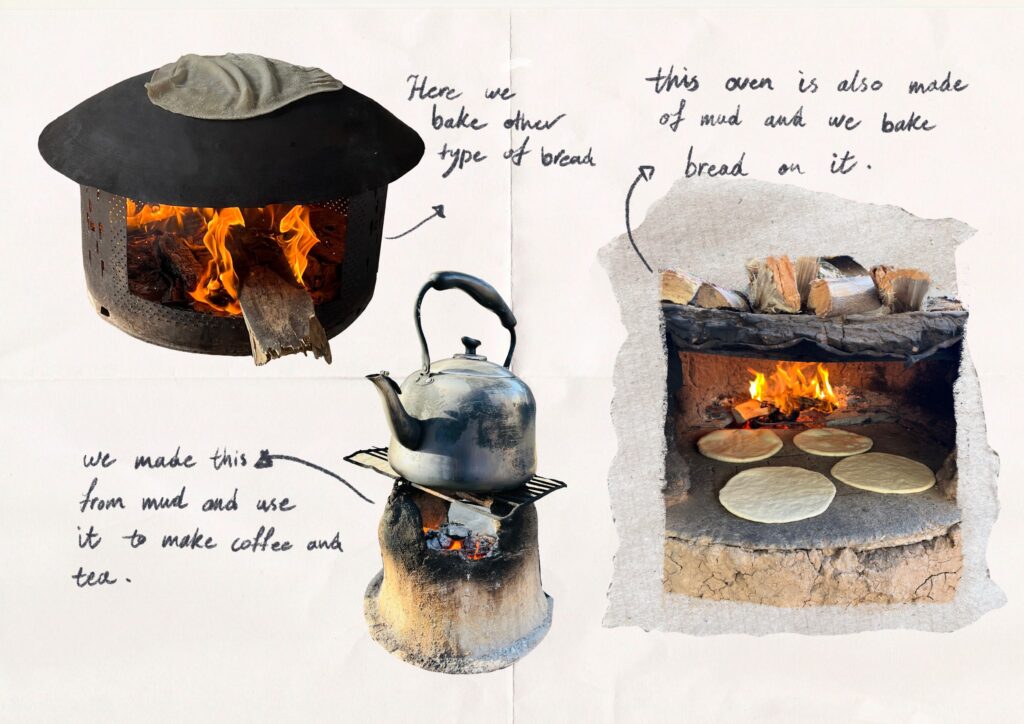

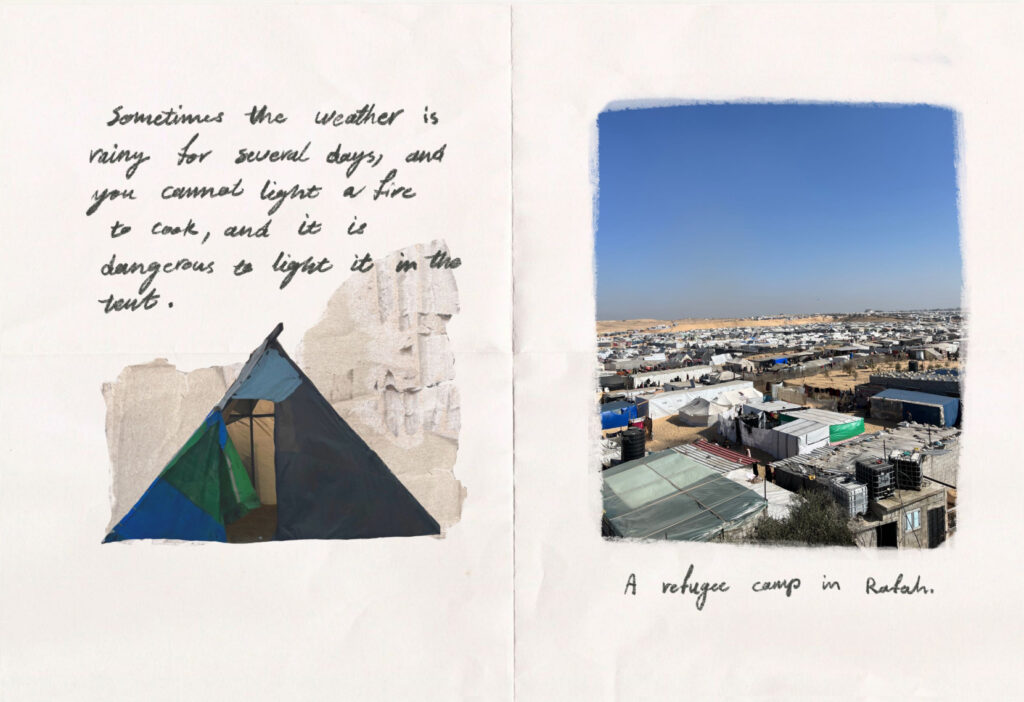

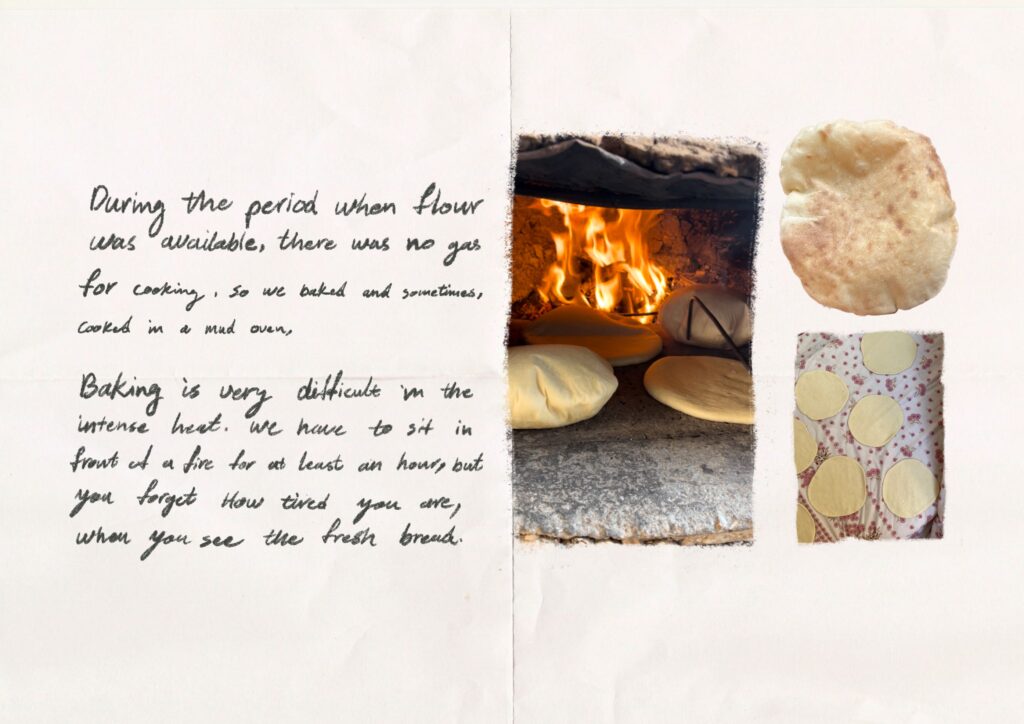

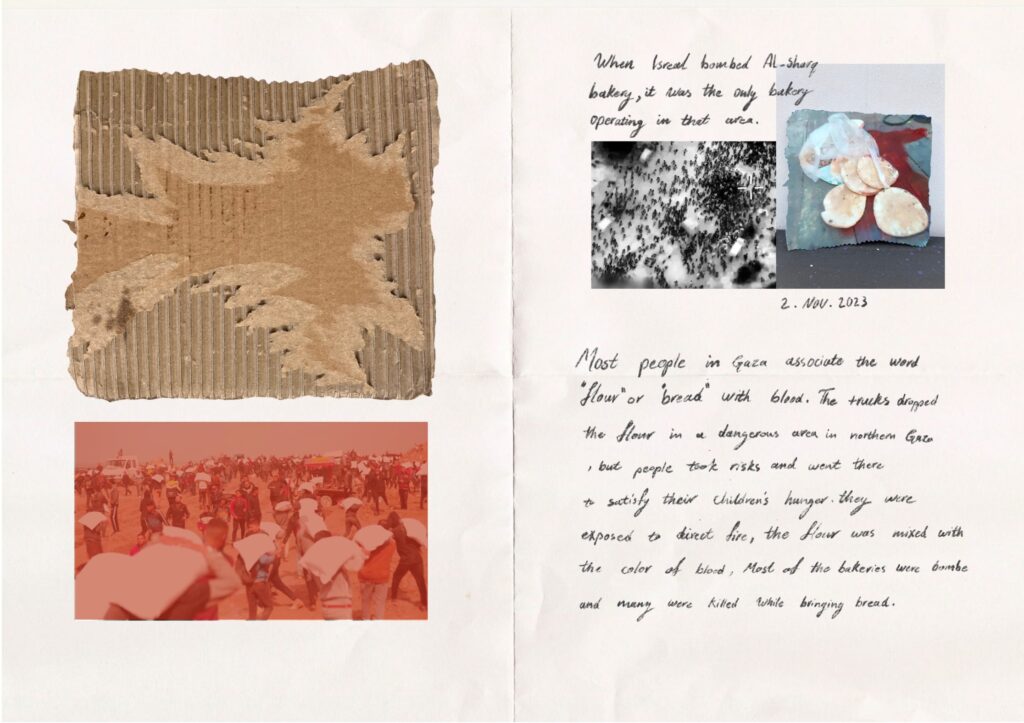

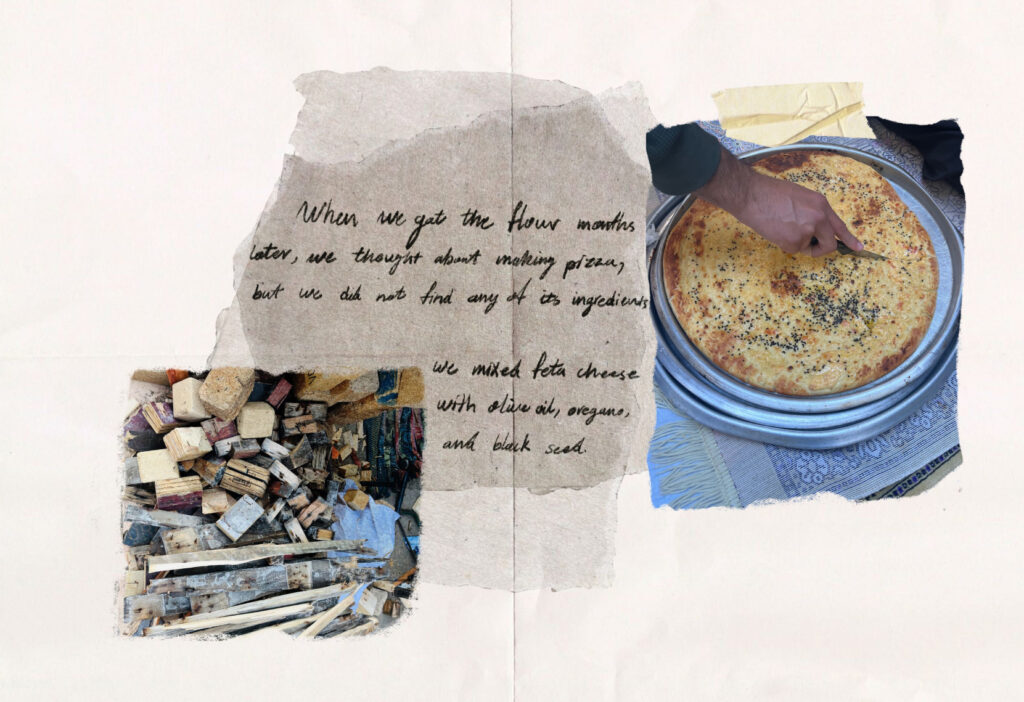

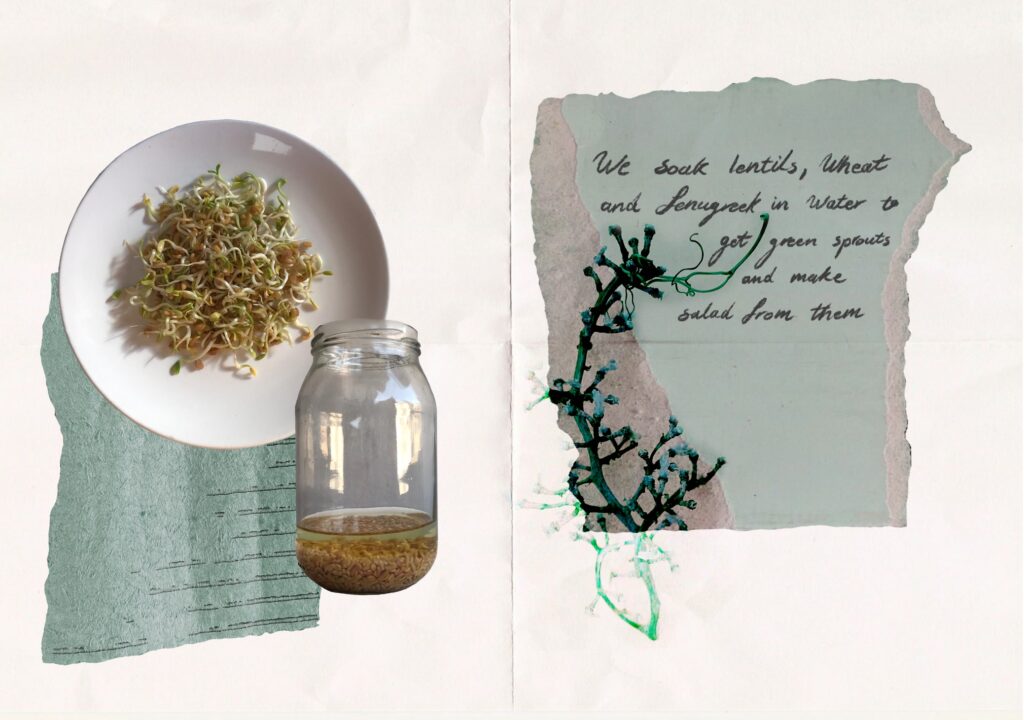

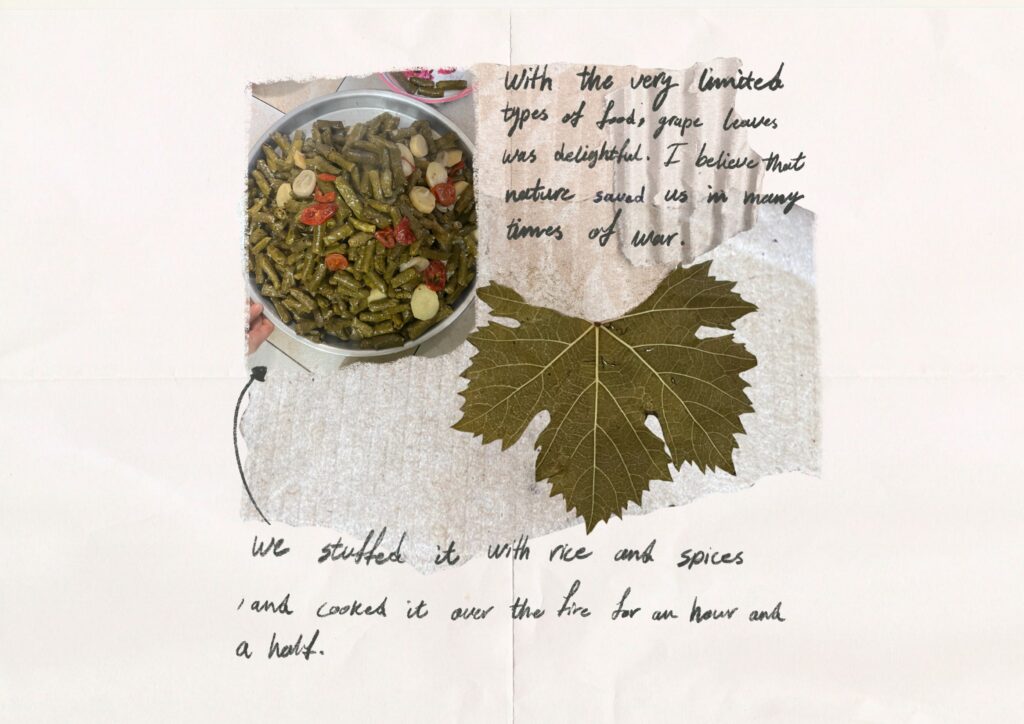

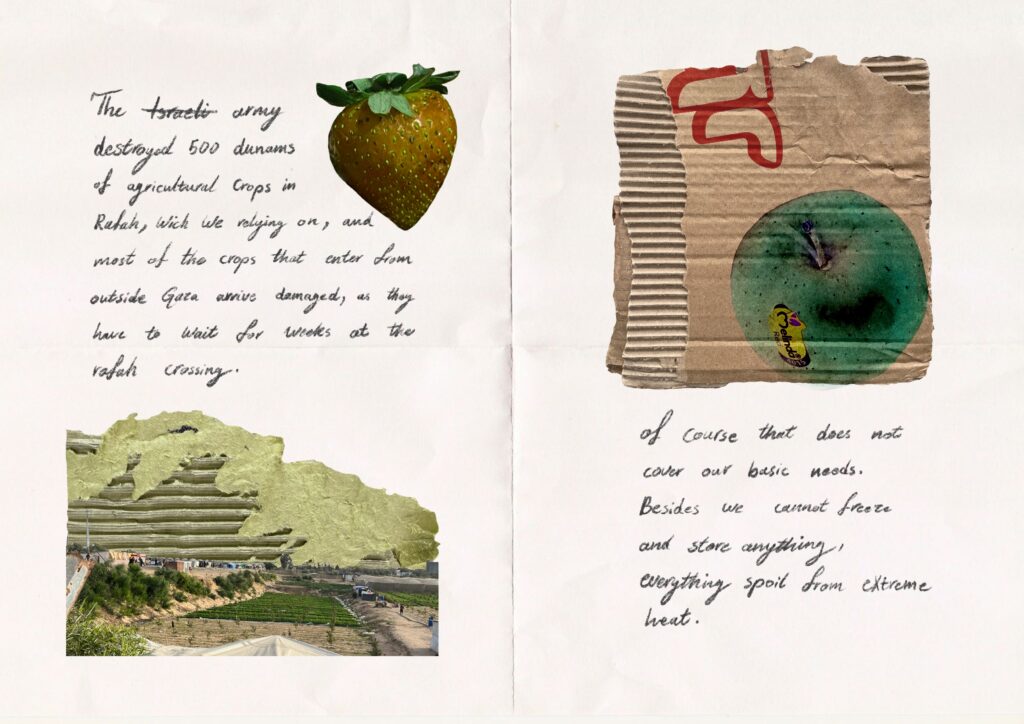

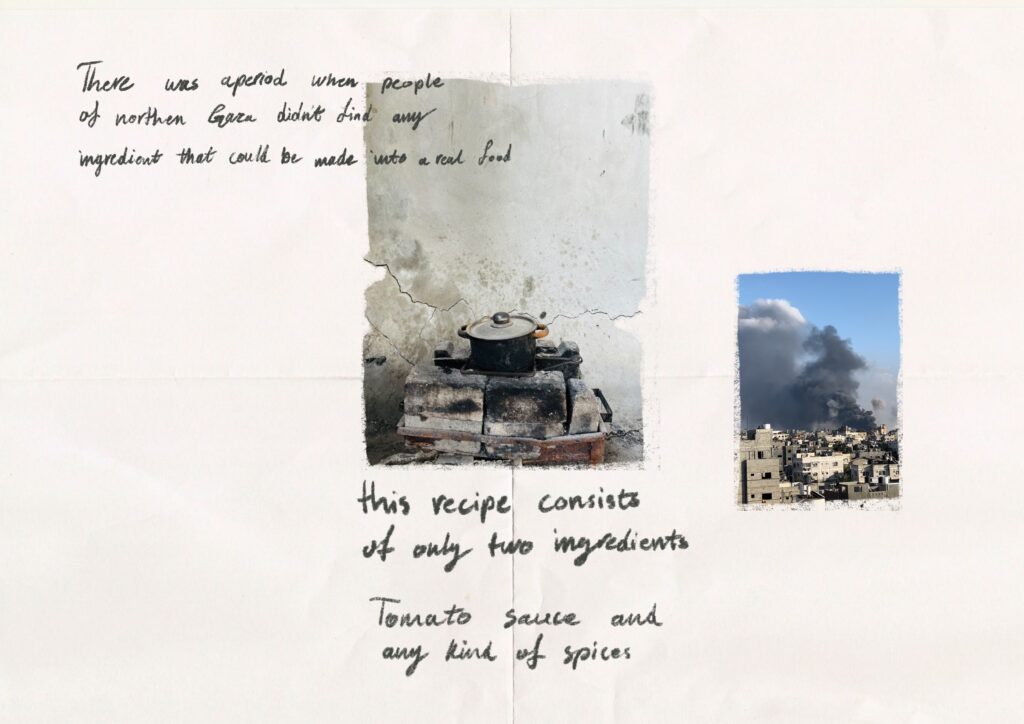

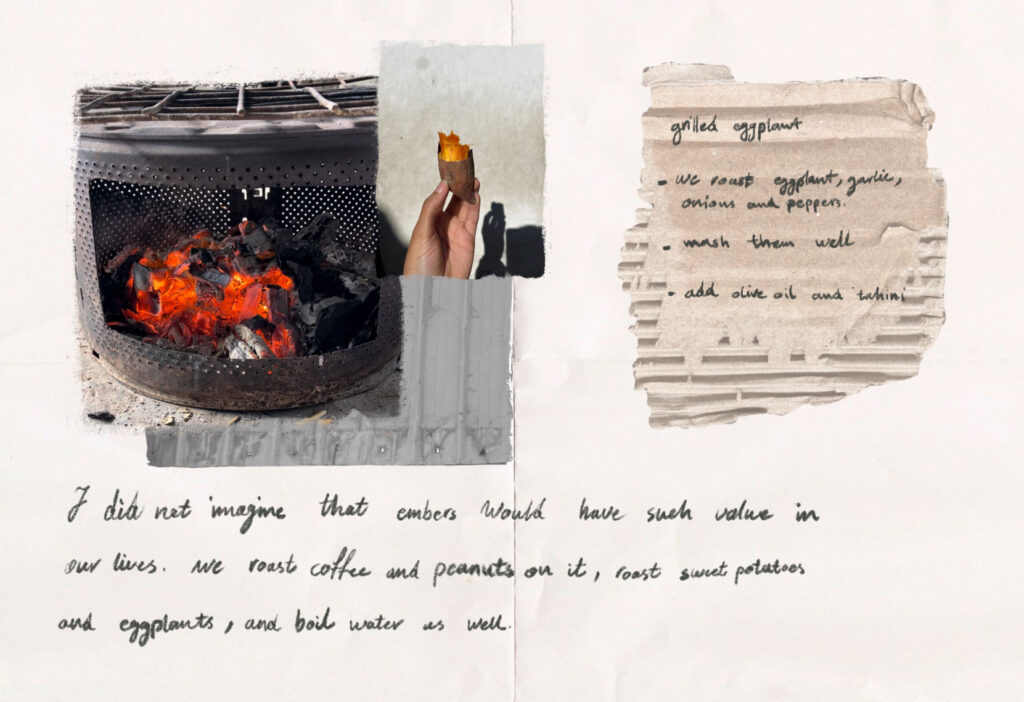

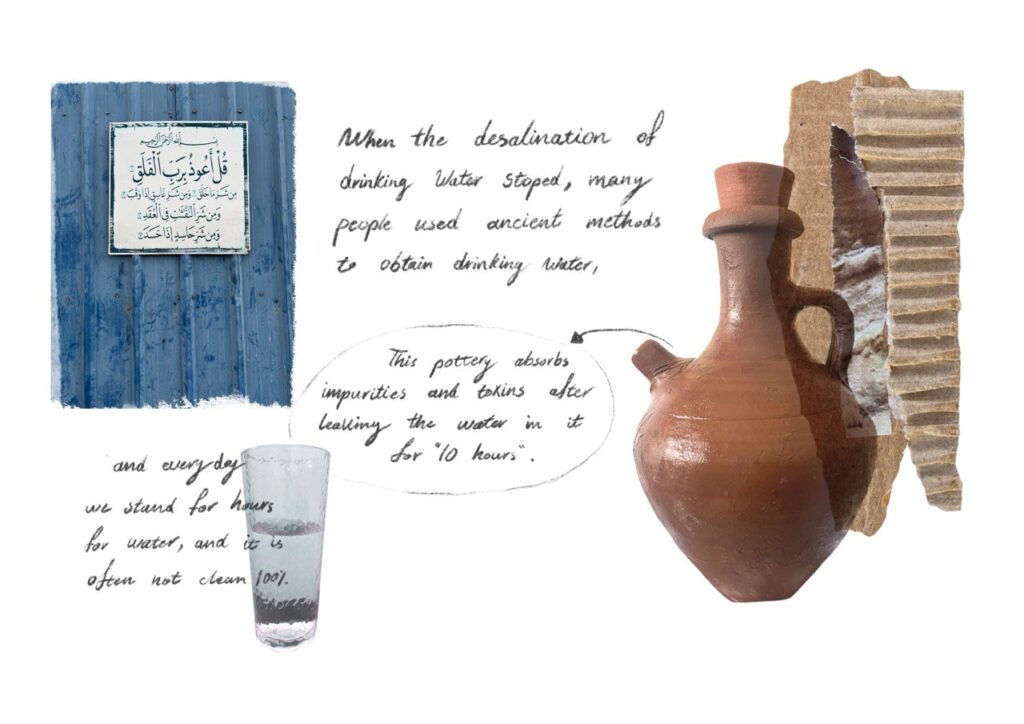

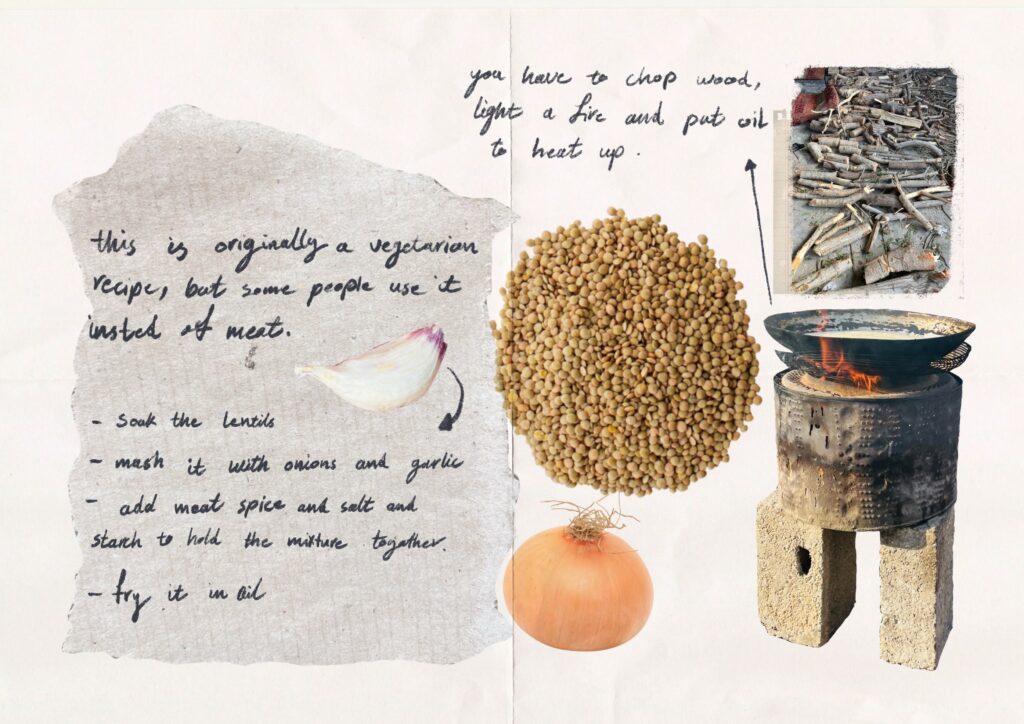

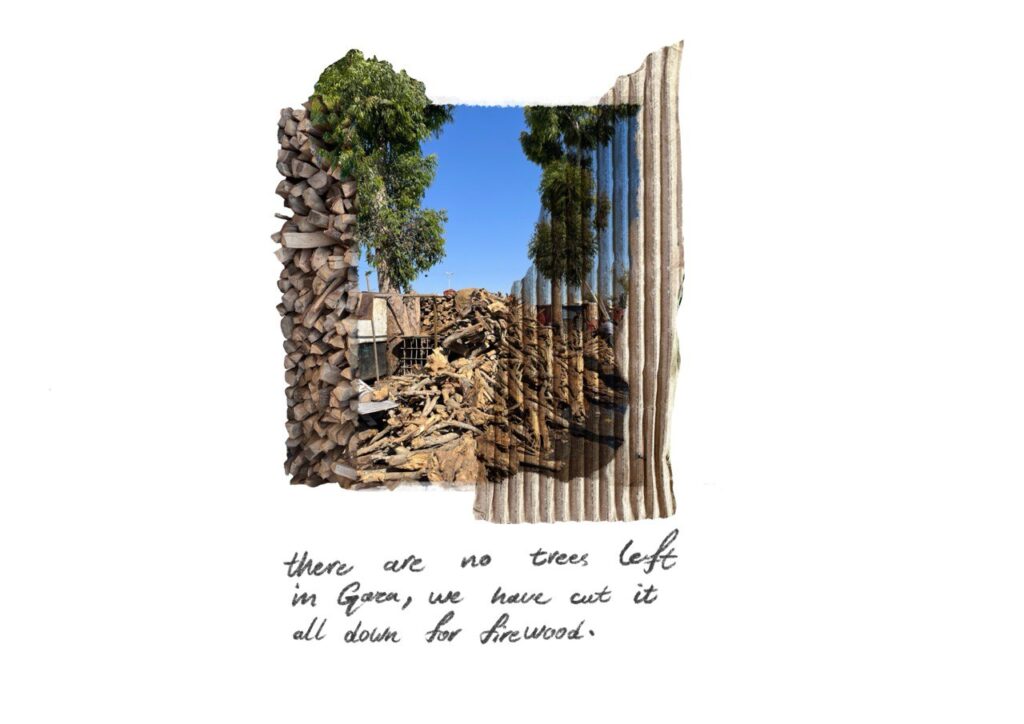

Samaa: It is because I know all too well how stressful it is to prepare the meal every day. I have lived through this myself and I know it is one layer of the many layers of annihilation. Through my work, I want to show the tremendous effort that goes into preparing every meal and all the details it involves; I want to show the greatness of the society that still does all of this on a daily basis, collecting wood, lighting the fire, bringing drinkable water. You have to add the high prices of food due to the closure of the crossings and the scarcity of resources to all this, not to mention the destruction of many agricultural lands, which are the main source of food for Gaza. It was, thus, necessary to invent new meals and solutions with the limited tools and things that we had available.

Sarazad: When did you start this project? Tell us about your point of departure, please.

Samaa: I started working on it two months ago. I was talking to a friend of mine and telling him about my desire to publish this Palestinian cook-book that I had finished drawing before the war. He suggested that I draw a new version to talk about cooking during the genocide, how we eat what we eat and how we live how we live. This is where the idea of The Genocide Kitchen came from. I wanted to describe our lives in its entirety, so that future generations as well as the world can see it_ if there is any merit in doing that.

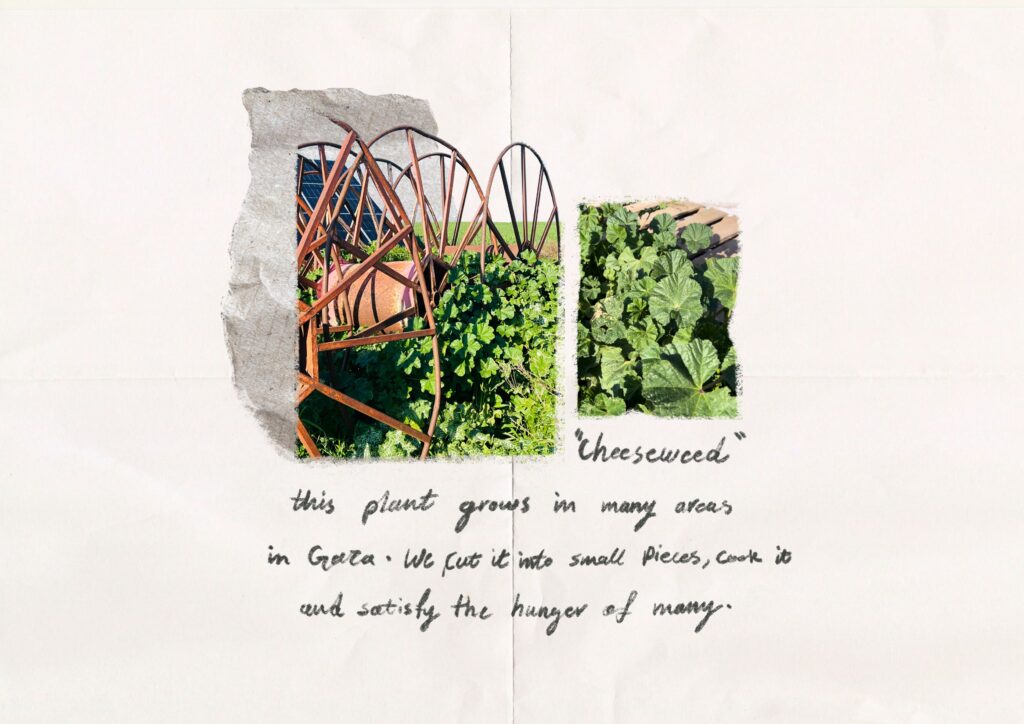

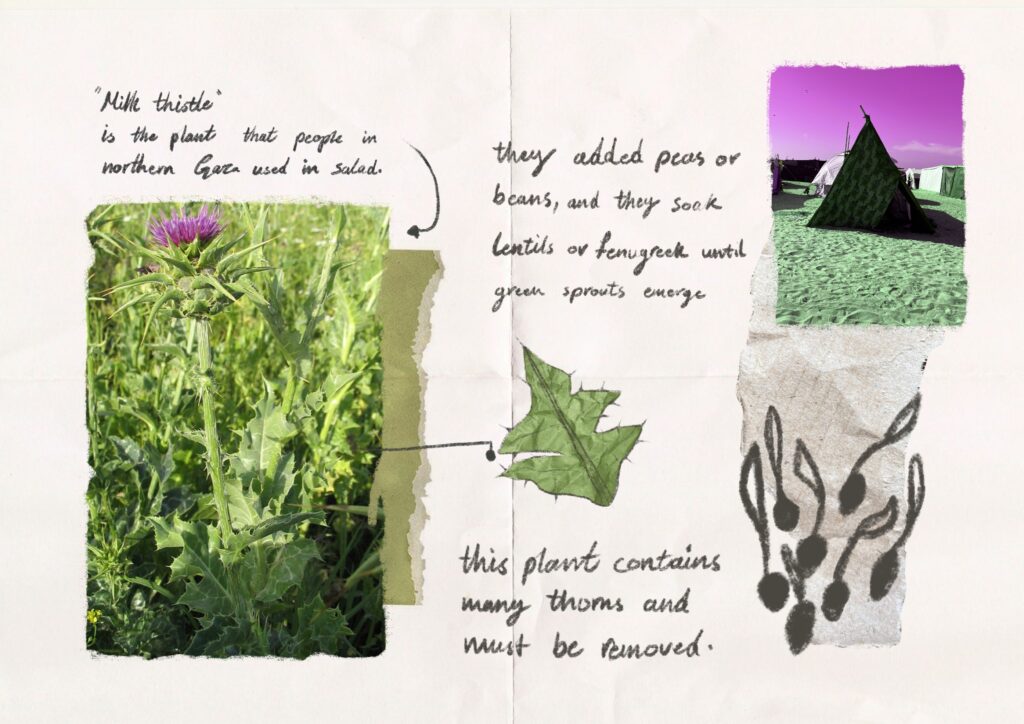

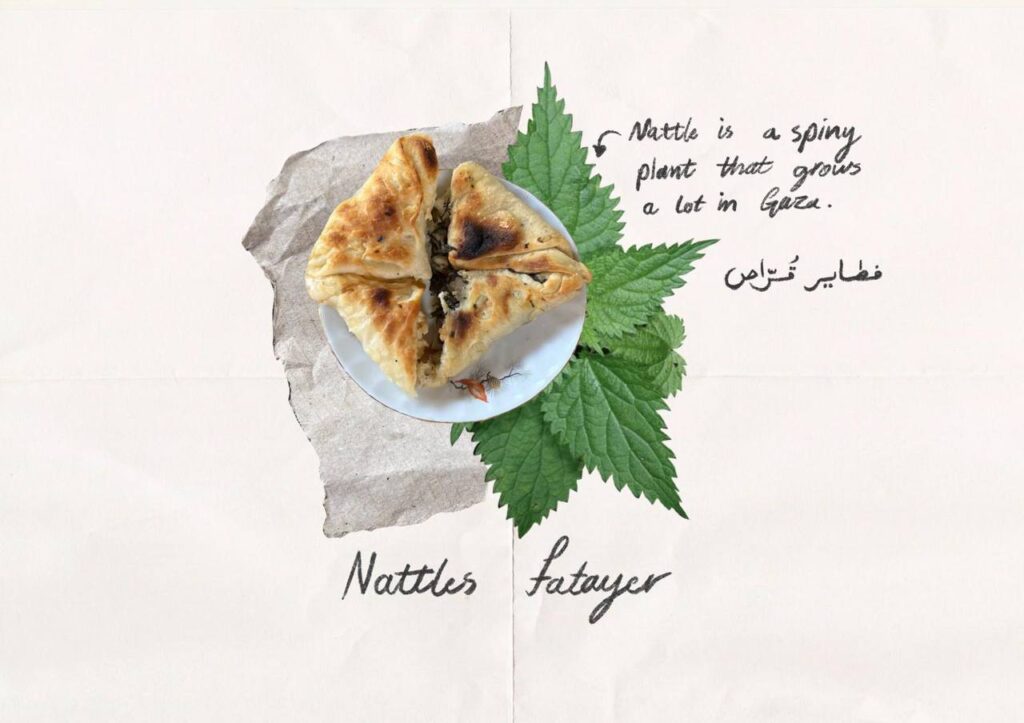

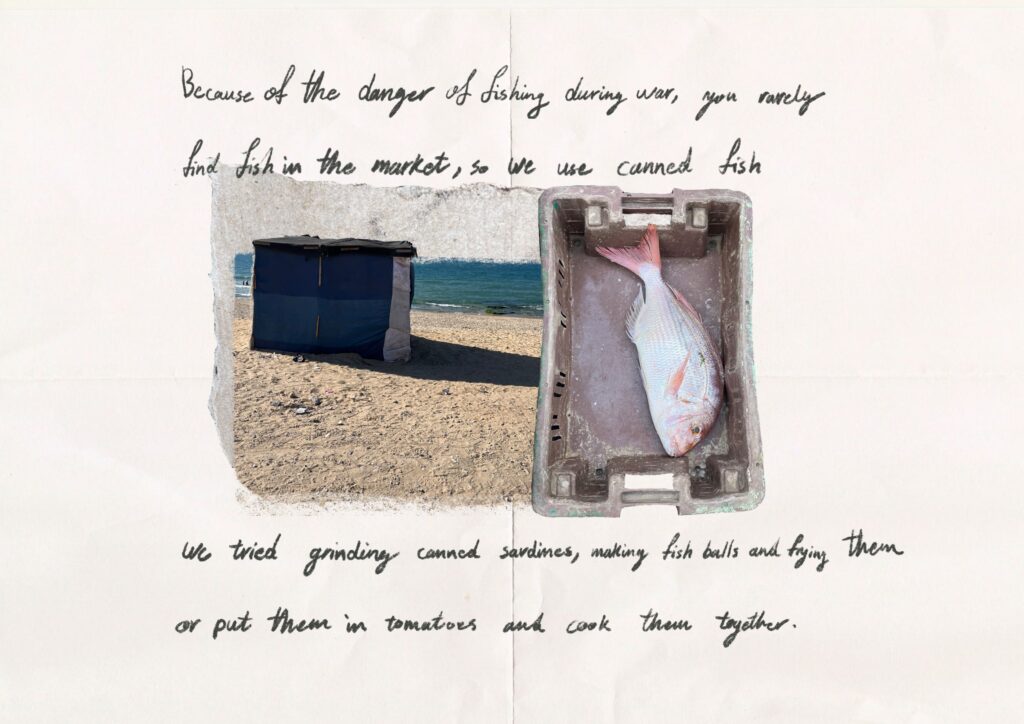

Sarazad: What does the mention of wild plants such as the nettle, which have replaced ordinary food in these months, as well as talking about the dangers of fishing and collecting firewood in the absence of gas say about the relationship of indigenous people with their land? Can we find a relation here with the land back movement among other indigenous communities?

Samaa: The land and its plants such as cheeseweed and nettle have saved many families from starvation. Occupation forces prevent aid and food supply trucks from entering Gaza. They do not allow boats to go fishing and open fire at them. But how can they prevent plants from growing? No-one can do such a thing. Most people started growing basic vegetables at home and in their tents. My vegetarian friend started sharing many recipes in which meet was replaced with legumes such as lentils. The occupation has cut off all lifelines of Gaza, but we always find some ways to survive, and as long as the land is with us, it will undoubtedly not cease giving and will continue to protect us from hunger and death.

Sarazad: As you mentioned, your method of expression has always involved photographs and collages. What capacities in these methods are attractive to you and what made you choose this way of expression?

Samaa: I believe that the raw material around us express who we are one way or another. I randomly collect different materials_ plastic, plants, cardboards, old magazines_ and then use them to create harmonious compositions which express certain feelings. I feel a certain necessity to collect these simple things which others think of as waste and to make something of greater value with them.

Sarazad: How did you manage to carry out the work in the conditions of genocide and frequent displacement, and how different was it from your usual way of working?

Sama: It was an extremely difficult thing to do because of the constant moving from one place to another and the fear that we felt all the time. I went to the displacement camps and tried to look for things that I wanted to photograph and many times I could not manage to do what I wanted. The interruptions in Internet connection and communication networks also made gathering information and recipes truly difficult. But in spite of all this, I was determined to do something and complete what I had started until the famine ends.

Sarazad: Could you elaborate more about the process of image making and collage as the method of your image production?

Samaa: In the past, I used to collect my material from the environment I lived in. I would use a special notebook and attach the material with glue, or sew them to the papers or sometimes burn parts of the material. These days, however, I used a digital tablet to make collage. I first photograph the items I want and then upload the images on my tablet. Even the torn papers which I use in many of my works are the one which I have photographed before, as there is no glue or paper left in the markets.

Sarazad: Your art is happening during the genocide; what do you think about the future of your images? What do you want them to do?

Samaa: When I hear the stories of 1948 Nakba and what happened to our ancestors, I often wonder what might have been like to live in displacement tents, far from one’s home and in dispersed and cut off areas. We do not have much specific evidence that document what exactly happened at that time. Documenting today’s events is tantamount to archiving the collective experience of Gazans. It can act as evidence to the crime of collective punishment through starvation. I want for what we are going through to be engraved in history. We should not allow the world to forget it.